![]()

Part I

Self-Related Motives Influence Close Relationships

![]()

Risk Regulation in Relationships: Self-Esteem and the If-Then Contingencies of Interdependent Life

SANDRA L. MURRAY

Romantic relationships pose a unique and unsettling interdependence dilemma. The thoughts and behaviors that are critical for satisfying close connections necessarily increase both the short-term risk and the long-term pain of rejection. Consequently, to risk a sense of connection, people need to feel safe and protected from potential hurts (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000).

Fortunately, the psychological insurance policy needed to risk connection to a partner—confidence in that partner's acceptance and love—is available within most relationships. People typically see their partner in a more positive and accepting light than their partner sees himself or herself (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 1996). Unfortunately, the people most in need of reassurance are least likely to perceive the level of unconditional acceptance they seek (Murray, Griffin, Rose, & Bellavia, 2006). People with low self-esteem underestimate how positively their partner regards their traits (Murray et al., 2000) and they also underestimate how much their partner loves them (Murray, Holmes, Griffin, Bellavia, & Rose, 2001). In contrast, people with high self-esteem correctly perceive their partner's positive regard and unconditional acceptance.

How do such differential expectations of partner acceptance affect the thoughts and behavior and the eventual romantic fates of low and high self-esteem people? This chapter examines this question by utilizing a model of relationship risk regulation (Murray, Holmes, & Collins, 2006). This model assumes that interdependent situations put the goal of promoting connection in conflict with the goal of avoiding painful rejections. By outlining the operation of this risk regulation system, this chapter specifies the imprint that resolving this goal conflict leaves on the relationships of low and high self-esteem people. In particular, it specifies how confidence in a partner's regard prioritizes the pursuit of relationship-promotion goals for people high in self-esteem and how doubts about a partner's regard prioritize the pursuit of self-protection goals for people low in self-esteem.

THE STRUCTURE OF INTERDEPENDENCE DILEMMAS

Situations of dependence are fundamental to romantic life. One partner's actions constrain the other's capacity to satisfy important needs and goals. Such dependence is evident from the lowest to the highest level of generality. At the level of specific situations, couples are interdependent in multiple ways, ranging from deciding whose movie preference to favor on a given weekend to deciding what constitutes a fair allocation of household chores. At a broader level, couples must negotiate different personalities, such as merging one partner's laissez-faire nature with the other's more controlled style (Braiker & Kelley, 1979; Holmes, 2002). At the highest level, the existence of the relationship itself requires both partners' cooperation.

A Recurrent Choice: Self-Protection or Relationship Promotion

Given multiple layers of interdependence, people routinely find themselves in situations where they need to choose how much dependence they can safely risk (Kelley, 1979). Take the simple example of a couple trying to decide whether to go to the current blockbuster action film or a contemplative arts film. Imagine that Sally confides to Harry that she believes that seeing the action film will help distract her from work worries, concerns that she fears the arts film Harry wants to see will only compound. In making this request, Sally is putting her psychological welfare in Harry's hands. Consequently, like most situations where some sacrifice on Hany's part is required, Sally risks discovering that Harry is not willing to be responsive to her needs. The exact nature of such situations may change throughout a relationship's developmental course. However, it is situations as these— situations of dependence where the partner's responsiveness to one's needs is in question—that activate the threat of rejection.

To establish the kind of relationship that can fulfill basic needs for belonging or connectedness, people must choose to risk substantial dependence on a partner in such situations (Murray, Holmes, et al., 2006). They need to behave in ways that give a partner power over their outcomes and think in ways that invest great value and importance in the relationship (Gagné & Lydon, 2004; Murray, 1999). For instance, people in satisfying relationships disclose self-doubts to their partner, seeking social support for personal weaknesses that could elicit rejection (Collins & Feeney, 2000; Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992). They also excuse transgressions when a partner has behaved badly, thereby opening the door for future misbehavior (Rusbult, Verette, Whitney, Slovik, & Lipkus, 1991).

Such relationship-promotive choices or transformations are critical for fostering satisfying relationships. However, they also compromise self-protection concerns by increasing the likelihood of rejection in the short term and intensifying how much the ultimate loss of the relationship would hurt (Simpson, 1987). After all, if Sally relies on Harry for support, she will inevitably expose herself to some less-than-supportive behavior on his part. Therefore, the intense social pain of losing a valued other should increase people's motivation to think and behave in ways that minimize dependence, limiting vulnerability to the partner's actions in the short term and diminishing the long-term potential pain of relationship loss.

OPTIMIZING ASSURANCE: THE RISK REGULATION SYSTEM IN RELATIONSHIPS

The risk regulation model assumes that negotiating interdependent life requires a cognitive, affective, and behavioral regulatory system for resolving the conflict between the goals of self-protection and relationship-promotion (Murray, Holmes, et al, 2006). The goal of this system is to optimize the sense of assurance possible given one's relationship circumstances. This sense of assurance is experienced as a sense of safety in one's level of dependence in the relationship—a feeling of relative invulnerability to hurt. To optimize this sense of assurance, this system must function dynamically, shifting the priority given to the goals of avoiding rejection and seeking closeness so as to accommodate the perceived risks of rejection.

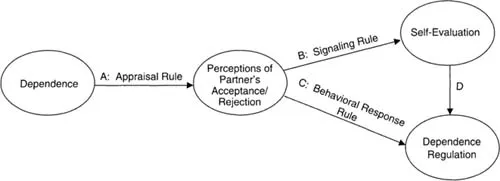

Figure 1.1 illustrates the normative operation of this risk regulation system. It illustrates three “if-then” rule systems people need to gauge the likelihood of a partner's acceptance or rejection and make the general situation of being involved in a relationship feel sufficiently safe. Gauging and regulating rejection risk requires appraisal (Path A), signaling or emotion (Path B) and behavioral response (Paths C and D) rules. These rule systems operate in concert to prioritize self-protection goals (and the assurance that comes from maintaining psychological distance) when the perceived risks of rejection are high, or relationship-promotion goals (and the assurance that comes from feeling connected) when the perceived risks of rejection are low.

FIGURE 1.1 The risk regulation system in relationships.

The Appraisal System

The link between dependence and perceptions of the partner's regard captures the assumption that situations of dependence increase people's need to gauge a partner's regard (Path A in Figure 1.1). This path captures the operation of an appraisal system. This contingency rule takes the form “if dependent, then gauge acceptance or rejection.”

To accurately gauge rejection risk, people need to discern whether a chosen partner is willing to meet their needs. II people are to risk connection, the outcome of this appraisal process needs to give them reason to trust in a partner's responsiveness to needs in situations of dependence (Reis, Clark, & Holmes, 2004; Tooby & Cosmides, 1996). The specific experiences that afford optimistic expectations about responsiveness likelv vary across relationships, and perhaps across cultures (Berscheid & Regan, 2005). From the perspective of the risk regulation model, the common diagnostic that affords confidence in a partner's expected responsiveness to needs is the perception that a partner perceives qualities in the self that are worth valuing—qualities that are not readily available in other partners. In more independent cultures, this sense of confidence requires the inference that a partner perceives valued traits in the self (Murray et al., 2000; Swann, Bosson, & Pelham, 2002). In more interdependent cultures, this sense of confidence requires the further inference that a partner's family also values one's qualities (MacDonald & Jessica, 2006).

The Signaling System

The link between perceived regard and self-evaluations (Path B in Figure 1.1) illustrates the operation of a signaling or emotion system that detects discrepancies between current and desired appraisals of a partner's regard and mobilizes action (Berscheid, 1983). The contingency rule governing the signaling system takes the form “if accepted or rejected, then internalize.”

This rule reflects a basic assumption of the socio meter model of self-esteem. Leary and his colleagues believe that the need to protect against rejection is so important that people have evolved a system for reacting to rejection threats (Leary & Baumeister, 2000; Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995; MacDonald & Leary, 2005). They argue that self-esteem is simply a gauge—a “sociometer”— that measures a person's perceived likelihood of being accepted or rejected by others. The sociometer is thought to function such that signs that another's approval is waning diminish self-esteem and motivate compensatory behaviors (Leary et al., 1995). In this sense, the sociometer functions not to preserve self-esteem per se, but to protect people from suffering the serious costs of rejection and not having their needs met.

The need for such a signaling system is amplified in romantic relationships because narrowing social connections to focus on one specific partner raises the personal stakes of rejection. In committing himself to Sally, Harry narrows the number of people he can rely on to satisfy his needs, and in so doing, makes his welfare all the more dependent on Sally's actions. In his routine interactions, Harry also does not need to seek acceptance from someone he perceives to be rejecting. However, in his relationship with Sally, he is often caught in the position of being hurt by the person whose acceptance he most desires.

Given all that is at stake, the signal that is conveyed by this rule system needs to be sufficiently strong to mobilize action (Berscheid, 1983). Perceiving rejection or drops in a partner's acceptance should hurt and threaten people's general and desired conceptions of themselves as being valuable, efficacious, and worthy of interpersonal connection (Baumeister, 1993; Taylor & Brown, 1988). By making rejection aversive, this signaling system motivates people to avoid situations where relationship partners are likely to be unresponsive and needs for connectedness are likely to be frustrated. In contrast, perceiving acceptance should affirm people's sense of themselves as being good and valuable, mobilizing the desire for greater connection and the likelihood of having one's needs met by a partner.

The Behavioral Response System

The link between perceived regard and dependence-regulating behavior captures the assumption that the threat and social pain of rejection in turn shape people's willingness to think and behave in ways that promote dependence and connectedness (Murray et al., 2000). This path illustrates the operation of a behavioral response system—one that proactively minimizes both the likelihood and the pain of future rejection experiences by making increased dependence contingent on the perception of acceptance (Paths C and D in Figure 1.1). As the direct and mediated paths illustrate, this system may be triggered directly, by the experience of acceptance or rejection (Path C in Figure 1.1), and indirectly, through resulting gains or drops in self-esteem (Path D in Figure 1.1). The contingency rule governing this system is “if feeling accepted or rejected, then regulate dependence.”

The risk regulation model assumes that the behavioral response system operates to ensure that people only risk as much future dependence as they feel is reasonably safe given recent experience. Suggesting that felt acceptance is a relatively automatic trigger to safety and the possibility of connection, unconsciously primed words that connote security (e.g., accepted) heighten empathy for others (Mikulincer, Gillath, Halevy, Avihou, Avidan, & Eshkoli, 2001), diminish people's tendency to derogate outgroup members (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2001), and increase people's desire to seek support from others in dealing with a personal crisis (Pierce & Lydon, 1998). In contrast, experiencing rejection elicits a social pain akin to physical pain so as to trigger automatic responses, such as aggression, that increase physical or psychological distance between oneself and the source of the pain (MacDonald & Leary, 2005).

Given the general operation of such a dependence regulation system, and the heightened need to protect against romantic rejection, people should implicitly regulate and structure dependence on a specific partner in ways that allow them to minimize the short-term likelihood and long-term potential pain of rejection (Murray et al., 2000). When a partner's general regard is in question, and rejection seems more likely, people should tread cautiously, reserve judgment, and limit future dependence on the partner.

A first line of defense might involve limiting the situations people are willing to enter within their relationships. Efforts to delimit dependence by choosing one's situations carefully might involve conscious decisions to seek support elsewhere, disclose less, or follow exchange norms. These strategies minimize the chance of being in situations where a partner might prove to be unresponsive. A second line of defense might involve shifting the symbolic value attach...