- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 8 Dec |Learn more

Essentials of English Grammar

About this book

This book was first published in 1933, Essentials of English Grammar is a valuable contribution to the field of English Language and Linguistics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Essentials of English Grammar by Otto Jespersen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I

Introductory

ESSENTIALS OF ENGLISH GRAMMAR

What is grammar?—Local and social dialects.—Spoken and written language.—Formulas and free expressions.—Expression, suppression, and impression.—Prescriptive, descriptive, explanatory, historical, appreciative grammar.—Purpose and plan of this grammar.

1.11. Grammar deals with the structure of languages, English grammar with the structure of English, French grammar with the structure of French, etc. Language consists of words, but the way in which these words are modified and joined together to express thoughts and feelings differs from one language to another.

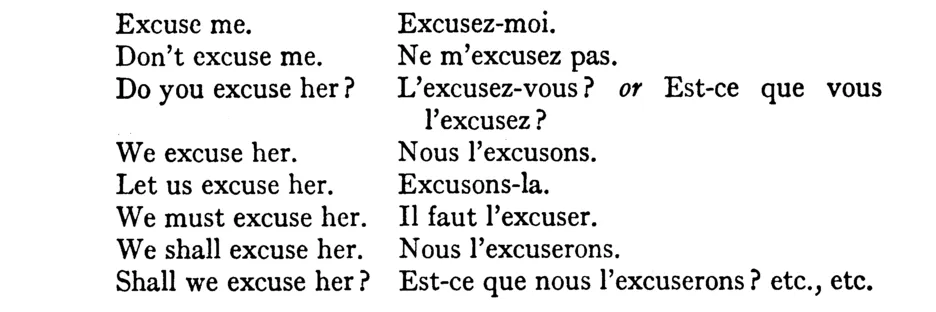

English and French have many words in common but treat them in a totally different way. Take the word excuse, which is spelt in the same way in the two languages. But the pronunciation is different, the vowel in the last syllable of the French word being unknown in English. In English we make a difference in pronunciation between to excuse and an excuse, but no such difference is made in French. Still greater differences appear when we make up complete sentences. Compare, for instance, the following:

1.12. The grammar of each language constitutes a system of its own, each element of which stands in a certain relation to, and is more or less dependent on, all the others. No linguistic system, however, is either completely rigid or perfectly harmonious, and we shall see in some of the subsequent chapters that there are loopholes and deficiencies in the English grammatical system.

Language is nothing but a set of human habits, the purpose of which is to give expression to thoughts and feelings, and especially to impart them to others. As with other habits it is not to be expected that they should be perfectly consistent. No one can speak exactly as everybody else or speak exactly in the same way under all circumstances and at all moments, hence a good deal of vacillation here and there. The divergencies would certainly be greater if it were not for the fact that the chief purpose of language is to make oneself understood by other members of the same community; this presupposes and brings about a more or less complete agreement on all essential points. The closer and more intimate the social life of a community is, the greater will be the concordance in speech between its members. In old times, when communication between various parts of the country was not easy and when the population was, on the whole, very stationary, a great many local dialects arose which differed very considerably from one another; the divergencies naturally became greater among the uneducated than among the educated and richer classes, as the latter moved more about and had more intercourse with people from other parts of the country. In recent times the enormously increased facilities of communication have to a great extent counteracted the tendency towards the splitting up of the language into dialects—class dialects and local dialects. In this grammar we must in many places call attention to various types of divergencies: geographical (English in the strictest sense with various sub-divisions, Scottish, Irish, American), and social (educated, colloquial, literary, poetical, on the one hand, and vulgar on the other). But it should be remembered that these strata cannot be strictly separated from, but are constantly influencing one another. Our chief concern will be with the normal speech of the educated class, what may be called Standard English, but we must remember that the speech even of "standard speakers" varies a good deal according to circumstances and surroundings as well as to the mood of the moment. Nor must we imagine that people in their everyday speech arrange their thoughts in the same orderly way as when they write, let alone when they are engaged on literary work. Grammatical expressions have been formed in the course of centuries by innumerable generations of illiterate speakers, and even in the most elevated literary style we are obliged to conform to what has become, in this way, the general practice. Hence many established idioms which on closer inspection may appear to the trained thinker illogical or irrational. The influence of emotions, as distinct from orderly rational thinking, is conspicuous in many parts of grammar—see, for instance, the chapters on gender, on expanded tenses, and on will and shall.

1.13. In our so-called civilized life print plays such an important part that educated people are apt to forget that language is primarily speech, i.e. chiefly conversation (dialogue), while the written (and printed) word is only a kind of substitute—in many ways a most valuable, but in other respects a poor one —for the spoken and heard word. Many things that have vital importance in speech—stress, pitch, colour of the voice, thus especially those elements which give expression to emotions rather than to logical thinking—disappear in the comparatively rigid medium of writing, or are imperfectly rendered by such means as underlining (italicizing) and punctuation. What is called the life of language consists in oral intercourse with its continual give-and-take between speaker and hearer. It should also be always remembered that this linguistic intercourse takes place not in isolated words as we see them in dictionaries, but by means of connected communications, chiefly in the form of sentences, though not always such complete and well-arranged sentences as form the delight of logicians and rhetoricians. Such sentences are chiefly found in writing, but the enormous increase which has taken place during the last few centuries in education and reading has exercised a profound influence on grammar, even on that of everyday speech.

1.21. There is an important distinction between formulas (or formular units) and free expressions. Some things in language are of the formula character—that is to say, no one can change anything in them. A phrase like "How do you do?" is entirely different from such a phrase as "I gave the boy a lump of sugar." In the former everything is fixed: you cannot even change the stress or make a pause between the words, and it is not natural to say, as in former times, "How does your father do?" or "How did you do?" The phrase is for all practical purposes one unchanged and unchangeable formula, the meaning of which is really independent of that of the separate words into which it may be analysed. But "I gave the boy sixpence" is of a totally different order. Here it is possible to stress any of the words and to make a pause, for instance, after "boy," or to substitute "he" or "she" for "I," "lent" for "gave," "Tom" for "the boy," etc. One may insert "never" or make other alterations. While in handling formulas memory is everything, free expressions involve another kind of mental activity; they have to be created in each case anew by the speaker, who inserts the words that fit the particular situation, and shapes and arranges them according to certain patterns. The words that make up the sentences are variable, but the type is fixed.

Now this distinction pervades all parts of grammar. Let us here take two examples only. To form the plural—that is, the expression of more than one—we have old formulas in the case of men, feet, oxen and a few other words, which are used so often in the plural that they are committed to memory at a very early age by each English-speaking child. But they are so irregular that they could not serve as patterns for new words. On the other hand, we have an s-ending in innumerable old words (kings, princes, bishops, days, hours, etc.), and this type is now so universal that it can be freely applied to all words except the few old irregular words. As soon as a new word comes into existence, no one hesitates about forming a plural in this way: automobiles, kodaks, aeroplanes, hooligans, ions, stunts, etc. In the sentence "He recovered his lost umbrella and had it recovered," the first recovered is a formular unit, the second (with a long vowel in the first syllable) is freely formed from caver in its ordinary meaning (4.62).

1.22. In all speech activity there are, further, three things to be distinguished, expression, suppression, and impression. Expression is what the speaker gives, suppression is what he does not give, though he might have given it, and impression is what the hearer receives. It is important to notice that an impression is often produced not only by what is said expressly, but also by what is suppressed. Suggestion is impression through suppression. Only bores want to express everything, but even bores find it impossible to express everything. Not only is the writer's art rightly said to consist largely in knowing what to leave in the inkstand, but in the most everyday remarks we suppress a great many things which it would be pedantic to say expressly. "Two third returns, Brighton," stands for something like: "Would you please sell me two third-class tickets from London to Brighton and back again, and I will pay you the usual fare for such tickets." Compound nouns state two terms, but say nothing of the way in which the relation between them is to be understood: home life, life at home; home letters, letters from home; home journey, journey (to) home; compare, further, life boat, life insurance, life member; sunrise, sunworship, sunflower, sunburnt, Sunday, sun-bright, etc.

As in the structure of compounds, so also in the structure of sentences much is left to the sympathetic imagination of the hearer, and what from the point of view of the trained thinker, or the pedantic schoolmaster, is only part of an utterance, is frequently the only thing said, and the only thing required to make the meaning clear to the hearer.

1.3. The chief object in teaching grammar today—especially that of a foreign language—would appear to be to give rules which must be obeyed if one wants to speak and write the language correctly—rules which as often as not seem quite arbitrary. Of greater value, however, than this prescriptive grammar is a purely descriptive grammar which, instead of serving as a guide to what should be said or written, aims at finding out what is actually said and written, by the speakers of the language investigated, and thus may lead to a scientific understanding of the rules followed instinctively by speakers and writers. Such a grammar should also be explanatory, giving, as far as this is possible, the reasons why the usage is such and such. These reasons may, according to circumstances, be phonetic or psychological, or in some cases both combined. Not infrequently the explanation will be found in an earlier stage of the same language: what in one period was a regular phenomenon may later become isolated and appear as an irregularity, an exception to what has now become the prevailing rule. Our grammar must therefore be historical to a certain extent. Finally, grammar may be appreciative, examining whether the rules obtained from the language in question are in every way clear (unambiguous, logical), expressive and easy, or whether in any one of these respects other forms or rules would have been preferable.

This book aims at giving a descriptive and, to some extent, explanatory and appreciative account of the grammatical system of Modern English, historical explanations being only given where this can be done without presupposing any detailed knowledge of Old English (OE., i.e. the language before A.D. 1000) or Middle English (ME., i.e. the language between 1000 and 1500) or any cognate language. Prescriptions as to correctness will be kept in the background, as the primary object of the book is not to teach English to foreigners, but to prepare for an intelligent understanding of the structure of a language which it is supposed that the reader knows already.

1.4. Grammatical rules have to be illustrated by examples. It has been endeavoured to give everywhere examples that are at once natural, characteristic, and as varied as possible. Many have been taken from everyday educated speech, while others have been chosen from the writings of well-known authors. It should be noted that in quotations from old books the spellings of the original editions have been retained; Shakespearian quotations are given in the spellings of the First Folio (1623), and Biblical quotations in the spelling of the Authorized Version (1611, abbreviated AV.), the only deviations being that the use of capitals and of the letters i, j, u, v has been made to conform to modern usage.

Apart from the phonological part which deals with sounds, grammar is usually divided into two parts: accidence—also called morphology—i.e. the doctrine of all the forms (inflexions) of the language, and syntax, i.e. the doctrine of sentence structure and the use of the forms. This type of division has been disregarded in this book, which substitutes for it a division in the main according to the chief grammatical categories. In most of the chapters the forms have first been considered and then their use, but more stress has everywhere been laid on the latter than on the former. In this way it is thought that a clearer conception is gained of the whole system, as what really belongs together is thus brought closely together.

1.5. As the system in this book differs from that followed in most grammars, a few new technical terms have been found necessary, but they will offer no serious difficulty; in fact, they are far less numerous than the terminological novelties introduced in recent books on psychology and other sciences. On the other hand, we have been able to dispense with a great many of the learned terms that are often found abundantly in grammatical treatises and which really say nothing that cannot be expressed clearly in simple everyday language.

Chapter II

Sounds

Phonetic script.—Lips.—Tip of t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- PREFACE

- Contents

- CHAPTER I INTRODUCTORY

- CHAPTER II SOUNDS

- CHAPTER III EVOLUTION OF THE SOUND-SYSTEM

- CHAPTER IV EVOLUTION OF THE SOUND-SYSTEM—continued

- CHAPTER V EVOLUTION OF THE SOUND-SYSTEM—concluded

- CHAPTER VI SPELLING

- CHAPTER VII PAGE WORD-CLASSES

- CHAPTER VIII THE THREE RANKS

- CHAPTER IX JUNCTION AND NEXUS

- CHAPTER X SENTENCE-STRUCTURE

- CHAPTER XI RELATIONS OF VERB TO SUBJECT AND OBJECT

- CHAPTER XII PASSIVE

- CHAPTER XIII PAGE PREDICATIVES

- CHAPTER XIV CASE

- CHAPTER XV PERSON

- CHAPTER XVI DEFINITE PRONOUNS

- CHAPTER XVII INDEFINITE PRONOUNS

- CHAPTER XVIII PAGE PRONOUNS OF TOTALITY

- CHAPTER XIX GENDER

- CHAPTER XX NUMBER

- CHAPTER XXI NUMBER—concluded

- CHAPTER XXII DEGREE

- CHAPTER XXIII PAGE TENSE

- CHAPTER XXIV TENSE—continued

- CHAPTER XXV WILL AND SHALL

- CHAPTER XXVI WOULD AND SHOULD

- CHAPTER XXVII PAGE MOOD

- CHAPTER XXVIII AFFIRMATION, NEGATION, QUESTION

- CHAPTER XXIX DEPENDENT NEXUS

- CHAPTER XXX NEXUS-SUBSTANTIVES

- CHAPTER XXXI THE GERUND

- CHAPTER XXXII PAGE THE INFINITIVE

- CHAPTER XXXIII CLAUSES AS PRIMARIES

- CHAPTER XXXIV CLAUSES AS SECONDARIES

- CHAPTER XXXV CLAUSES AS TERTIARIES

- CHAPTER XXXVI RETROSPECT

- INDEX