- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A Secret World is a valuable contribution to the field of Family Therapy. Looks at the history and origins of celibacy, discusses its role in the priesthood, and considers the psychological aspects of celibacy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

THE BACKGROUND AND THE CONTEXT

Chapter 1

WHY THIS SUBJECT? Apologia Pro Studiis Suis

His great subject was the relation of corruptible action to absolute principle; of worldly means to transcendent ends; of historical commitment to personal desire.

—Irving Howe

Introduction to Bread and Wine (Silone)

The potential value of this study lies in the questions that it addresses: What is celibacy? How is it really practiced by those who profess it? What is the process of celibacy? What is the structure of celibate achievement?

In short, this is a search for a structural and dynamic model of an ancient practice that crosses cultural and religious boundaries. Although this study is limited to Catholic priests in the United States, the questions are meaningful to the understanding of celibate practice universally, including the Buddhist and Hindu traditions. The most commonly assumed definition of “celibate” is simply an unmarried or single person, and celibacy is perceived as synonymous with sexual abstinence or restraint. Those assumptions, although incomplete for the purpose of our study, will be sufficient to sustain the reader for the first three chapters. In Chapter 4, a more precise definition will be delineated both to amplify and to challenge incomplete notions.

In spite of the fact that celibacy has not been a constant tradition even in the Roman Catholic Church, there is a common psychic presumption of a “virginal” clergy which even extends to the Jewish rabbinate. More than one psychologically sophisticated rabbi has told me that they are aware of this phenomenon among members of their congregations. Especially in the celebration of any sacred service or in the recitation of sacred texts, clerical acts and words need to be separated in the minds of the faithful from the sexuality of the minister, much as children must separate their parents from any sexual “contamination.”

Questions about celibacy are not commonly asked, nor do they very often stir common interest. Some justification—apologia in the traditional sense—may help the reader understand why anyone would pursue such questions systematically for 25 years and, more important, why the subject of celibacy should merit a reader's time and interest.

SEX/CELIBACY: BREAKING THE TABOO

The time period spanned by this search is the quarter-century that has marked the “sexual revolution.” We have learned a great deal about/from sexual expression and sexual indulgence in these 25 years. However, there is also much to be learned about sexuality from sexual restraint and abstinence. C. S. Lewis noted that you learn more about an army by resisting it than by surrendering to it.

What better examples of sexual control are there than those who publicly profess a life full of meaning yet devoid of sex—Roman Catholic priests? Yet information that would seem so easily accessible from every priest by the simple question—What is your sexual/celibate adjustment?— is often shrouded in secrecy, denial, and mystery, even to the priest himself.

“Before the 60s, celibates were presumed to have no sexuality. Any priest who showed signs of sexuality was considered at least strange,” said a priest participant in a dialogue on the sexual maturing of celibates (Tet-low, 1985). Asking a priest about his celibacy is like asking a banker about his honesty—if one questions the closely guarded and highly defended assumptions, insult, confusion, and even rage result.

Carl Eifert, a lay spokesman for the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, asserted in an interview with Gustav Niebuhr that statements by U.S. bishops on the issue of celibacy are “based on the assumption that priests are consistent in their adherence to their vows” (Niebuhr, 1989). A priest spokesman for the same agency was typically defensive about the suggestion made in prepublication material from this work that a substantial proportion of professed celibates do indeed have a sexual life. Said he, “Priests are humans and have feelings; but the great, great majority of priests that I know are faithful to their vows. I know hundreds and hundreds of priests—it's certainly not true.” (Niebuhr, 1989).

This study looks for fact beyond all the assumptions—both positive and negative—about celibacy, for there are equally unfair contrary suppositions surrounding celibacy, and not only among secular nonbelievers. One middle-aged priest, a poetic cynic, said, “Celibacy is like the unicorn—a perfect and absolutely noble animal. … I have read eloquent descriptions of it and have seen it glorified in art. I have wanted desperately to believe in its existence, but alas, I have never been able to find it on the hoof” (personal communication).

In short, even priests who know “hundreds and hundreds of priests” often do not know the sexual/celibate adjustment of even their closest friends, as we found time and time again in our search. This adjustment is mostly a secret one. A priest's sexual/celibate life becomes visible primarily through a scandal in which a pregnancy, a lawsuit, or an arrest comes to public attention.

Some priests will share the secret of their celibate achievement or compromise in the confessional or, as it is called now, the sacrament of reconciliation. However, many priest informants in our study revealed that they do not consistently confess what might at least technically be termed a transgression of the vow or the practice of celibacy, e.g., masturbation.

Whereas confession can be accomplished in the dark and anonymously, spiritual direction and psychotherapy are two areas in which a priest can reveal his intimate life-style and deal openly and yet in a privileged manner with issues of sexuality. During the period of our study, priests increasingly talked more openly to friends or in small groups about their sexual struggles. In Chapter 2, I expand on the shifting sociosexual context that made this study of celibacy possible. Individual revelations and collections of data can make the penetration of the veil of secrecy possible and useful both to those who wish to understand sexuality better and to those who wish to live celibacy effectively.

The factors outlined in Chapter 2 are among many that provided a window into the hitherto secret world of the celibate. The ideal of celibacy has been gloriously extolled throughout history, just as it has been inglo riously ridiculed. However, it has never been examined in a way that could open it to scientific research. This study is an attempt to make such research more plausible.

There is no unseemliness in attempting to examine the secrets of celibate practice and achievement. In fact, Pope John Paul II, in speaking to journalists on January 27, 1984, said, “The Church endeavors and will always endeavor more to be a house of glass, where all can see what happens and how it fulfills a mission” (Baltimore Sun, Jan. 28, 1984). He was speaking in a general sense, and certainly not specifically about celibacy, but how could he exclude an element so vitally entwined with the priesthood? Personal celibacy is a public stance. Religious leaders and their own personal standards contribute significantly to the understanding of sexuality and sexual morality among their flocks. Certainly, the public witness and teaching of the clergy cannot be separated from their personal attitudes toward sexuality and the observance of their vow.

HISTORY: THE BROADER CONTEXT

Henry C. Lea wrote a classic nineteenth-century study of sacerdotal celibacy. He hoped that his study would be of interest to the general reader, “not only on account of the influence which ecclesiastical celibacy has exerted, directly and indirectly, on the progress of civilization, but also from the occasional glimpse into the interior life of past ages afforded in reviewing the effect upon society of the policy of the church as respects the relations of the sexes” (Lea, 1884). Lea wrote that for the preface to the 1867 edition of his study.

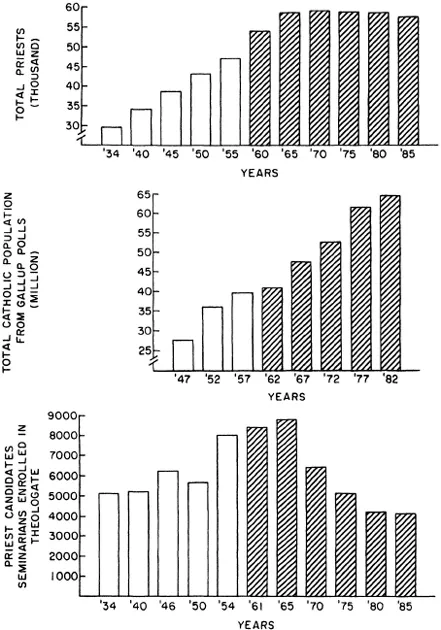

FIGURE 1:1. Top, growth in the U.S. priest population from 1934 through 1985. Center, growth in the general U.S. Catholic population during the same time period. Bottom, number of priest candidates enrolled in the seminaries in the United States during this period.

However, where Lea focused on the interior life of past ages, I focus on the current picture and hold the same hope that he did. I have invoked the broader context of celibacy and historical connections wherever I thought they would help the reader understand the aspects of celibate practice being discussed or wherever they might be of interest. Unlike Lea, I do believe that celibacy has its genuine origin in the apostolic community, but I am well aware that it was not then nor in the first Christian millennium a universal requirement for the priesthood. 1 think that it is necessary to put celibacy into its historical reality (cf. Chapter 3) for two reasons: (1) for an understanding of its relationship to ministry, and (2) to delineate clearly the problems of charism (or spiritual grace) versus discipline (church law).

I believe that the careful reader will find this study free of some of the bias attributed to Lea.

One final comment on the historical context is in order. In 1960, there were 53,796 Catholic priests in the United States and about 8,000 men in the final four years of their preparation for ordination. In 1985, 57,317 priests were recorded as active, with 4,063 men studying (Hoge, 1987, p. 229). If one looks at the priest population since 1934 (see Figure 1.1, top), one cannot help but be struck by the steady progress in numbers between 1935 and 1965 in glaring contrast to the plateau and decrease in total numbers between 1965 and 1985. The leveling of the total priest population is another factor that made this study possible during these years. This leveling does not reflect the growth in the total Catholic population in the United States (see Figure 1.1, center) during this same time period. The concomitant decrease in candidates for the priesthood (Figure 1.1, bottom) is at least in part due to a decline in the understanding and appeal of celibacy (Hoge, 1987).

FORMAT AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY: WHAT IT IS AND WHAT IT IS NOT

There is currently a hot debate in clerical circles about a married clergy versus a celibate priesthood. This study is not a defense of either position. The facts and analysis that follow can be used to support either view, just as they challenge partisans of both to a deeper understanding and clarification of their arguments.

This work is based upon interviews with and reports from approximately 1500 people who have firsthand knowledge of the sexual/celibate adjustment of priests. One-third of the informants were priests who were in some form of psychotherapy either during inpatient or outpatient treatment. The clinical setting provides a tremendous advantage in gathering personal information because of the depth and duration of the observation. It is not merely the sexual behavior or the celibate ideal that is revealed or recorded, but the person—the history, development, and context of a life that can be observed and analyzed. Brief evaluations and longer treatment modalities have both contributed to the insights garnered for this study. Several reports from psychoanalysis were available to us; the longest involved 1700 sessions.

A word of caution is necessary for those who are unaware of psychotherapy or who have a bias against persons who enter it. To see those who use psychotherapy as “sick” and thereby dismiss them and their observations is like denigrating anyone who uses the sacrament of reconciliation as merely a “sinner” who has nothing to teach us about values and virtue. Also, one who is sexually active, even if vowed to celibacy, may indeed be beset by a conflict of values but may be “healthy” sexually.

Another third of the informants were clergy who were not patients but who shared information during meetings, interviews, and consultations, both individually and in small groups. The secular cultural upheaval of recent decades as well as that resulting from the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) made priests more self-aware, as well as open and searching, especially during retreats and workshops, as well as in training programs. Each man knew not only his own sexual/celibate history but also had some observation, experience, or knowledge of the sexual/celibate experience of the group with whom he lived or worked. As a confessor, religious superior, or confidant of others, he brought a perspective to the subject that no outsider could expect to master alone or through a mere attitudinal survey. A number of men from this group have kept contact with this study from five to 10 years, and a handful endured most of the 25 years.

The remaining third of the informants were especially valuable in validating and corroborating the priests’ observations and conclusions because they had a perspective on priests who themselves would never have reported on their sexual/celibate adjustment. This group had firsthand information on the priests’ behavior because they were their lovers, sexual partners, victims, or otherwise direct observers of it. This group included both men and women, married and single, nuns, seminarians, and men who had left the priesthood. The first data were recorded from this group in 1960 but increased as the study progressed, especially in the years 1975-1985.

There are undoubtedly readers who will cry “foul” at the fact that estimates of celibate practice and achievement are made on the basis of the life experience of 1500 men. “They are the sick ones,” or “They are the exceptions,” may be the first lines of defense against the simple facts. All of us involved in making generalizations and estimates from the facts available to us were so cautious and had so much time and opportunity to revise our calculations that I am confident that if we have erred at all, it is on the side of conservative percentages.

We consistently asked informants to estimate the sexual/celibate practice among their group or in their area. We took into account the relative viewpoint of each man reporting. If there was a vested interest in a response, that interest was taken into account. For instance, a bishop or religious superior would sometimes present a case or series of cases for consultation while stating defensively that these were the “only” such instances, whereas active homosexual priests who knew of one or more other active homosexual priests tended to make relatively high estimates. Persons with a relatively long association with the study or who had broad past experience within clerical circles offered estimates remarkably close to ours. Older participants tended to have higher rather than lower estimates; however, there were startling exceptions to that rule also.

Priests have at their disposal an important tool enabling them to be in touch with the “sexual truth”—confession. Michel Foucault (1978), in The History of Sexuality, points out the broadest implications of this vehicle of knowledge and power:

Since the Middle Ages at least, Western societies have established the confession as one of the main rituals we rely on for the production of truth: the codification of the sacrament of penance by the Lateran Council in 1215, with the resulting development of confessional techniques, the declining importance of accusatory procedures in criminal justice, the abandonment of tests of guilt (sworn statements, duels, judgments of God), and the development of methods of interrogation and inquest, the increased participation of the royal administration in the prosecution of infractions at the expense of proceedings leading to private settlements, the setting up of tribunals of Inquisition: all this helped to give the confession a central role in the order of civil and religious powers, (p. 58)

A confessor will have an approach different from a therapist. A priest is trained to “forgive sins” as an agent of God. The slate is wiped clean upon the acknowledgment of an act, its repentance, and a firm resolve not to repeat it in the future. The observer of human behavior cannot be quite so segmented in evaluating the sexual/celibate behavior of a person. For instance, a priest may be sexually involved with another person only four times a year for a period of a few years. According to the former calculation, this man can be judged to be celibate with some periodic lapses due to human frailty. The student of celibacy who cannot relegate the behavior merely to the category of sin will not necessarily see the sexual behavior as unrelated sexual acts or as behavior divorced from the man's sexual/celibate orientation or adjustment. As one lay informant said of these four annual “lapses,” “That's as much sexual activity as some married folks have.”

In some instances we have included the ages of ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Part I The Background and the Context

- Part II The Practice Versus the Profession

- Part III The Process and the Attainment

- References

- Additional Readings

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Secret World by A.W. Richard Sipe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Human Sexuality in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.