- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of China

About this book

First published in 1950. This re-issues the fourth edition of 1977.This is a social history of China, presenting the main lines of development of the Chinese social structure from the earliest times to the present day. The book discusses the origins of the present regime and developments in China in the last years, and political, social and cultural changes are all analyzed.The text is based upon the study of original Chinese sources and also the work of Chinese, Japanese and Western scholars.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of China by Wolfram Eberhard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Prehistory

1Sources for the earliest history

Until recently we were dependent for the beginnings of Chinese history on the written Chinese tradition. According to these sources China's history began either about 4000 B.C. or about 2700 B.C. with a succession of wise emperors who ‘invented’ the elements of a civilization, such as clothing, the preparation of food, marriage, and a state system; they instructed their people in these things, and so brought China, as early as in the third millennium B.C., to an astonishingly high cultural level. However, all we know of the origin of civilizations makes this of itself entirely improbable; no other civilization in the world originated in any such way. As time went on, Chinese historians found more and more to say about primeval times. All these narratives were collected in the great imperial history that appeared at the beginning of the Manchu epoch. The older historical sources make no mention of any rulers before 2200 B.C., no mention even of their names. The names of earlier rulers first appear in documents of about 400 B.C.; the deeds attributed to them and the dates assigned to them often do not appear until much later.

Modern research has not only demonstrated that all these accounts are inventions of a much later period, but has also shown why such narratives were composed. We will discuss this later at the appropriate moment, but briefly mention that on the one hand these accounts can be seen as an attempt of Chinese philosophers to explain the development of culture and society and to use them to legitimize the system of government that existed in their time. On the other hand, the accounts served to legitimize the aspirations and actions of particular persons or groups of persons.

Furthermore, we can now state with certainty that all historical data which were given in written documents for times down to about 1000 B.C. are false. They are the result of astronomical-astrological calculations, made by specialists of later times who pursued their own special political aims by doing these calculations. To this day, we do not have written sources which are earlier than c. 1300 B.C., but we have reason to say that persons and activities mentioned in sources written after that time and said to have lived before it, really did live and seem to have done certain actions, perhaps up to the time shortly before 2000 B.C. There is, however, no reason to accept anything that is said in later sources about periods before 2000 B.C. as ‘historical’. Strictly speaking, then, a history of China should not begin before the time for which written documentation exists. During the last 50 years, numerous excavations have been made on the territory of the People's Republic of China, but to call the cultures which have been found, ‘Chinese’ is just about as logical as to call the people of Mohenjo Dharo ‘Pakistani’. We now know definitely, though not all the evidence has been published, that on the territory of China people of different cultures and even of different races lived. We also know that in present-day China people of different cultures live as minorities, though ‘racially’ most of them are not different from ‘Chinese’, and we know that the people who now call themselves ‘Chinese’ do not all have all the same racial origins—in whichever way we may define this controversial term ‘race’. The matter is not a matter of race or language and not a matter of territory. We should speak of ‘Chinese’ from the moment that we can find a group of people under an organized government, a form of ‘state’ that regards itself as a group with a common culture and as different from other groups. From at least 1000 B.C. on, we find a clear term which the Chinese used for themselves and which excluded others. As the state of that time was a clear continuation of an earlier state, we can speak of ‘Chinese’ probably from about 1500 B.C. on. What is before this time should be called ‘pre-Chinese’ and we can study this period only by means of archaeology and comparative ethnology. However, both methods tend to give different results.

2The earliest periods

For the earliest period, we have nothing but a few excavations. Actually, we cannot expect very many traces of the first man, as there were probably only a few small hordes in some places of the Far East. The main settlement which we know consists of caves in Chou-k'ou-tien, south of Peking. Here lived the so-called ‘Peking Man’. He is vastly different from the men of today, and forms a special branch of the human race, closely allied to the Pithecanthropus of Java. The formation of later races of mankind from these types has not yet been traced, if it occurred at all.

The Peking Man lived in caves; no doubt he was a hunter, already in possession of very simple stone implements and also of the art of making fire. As none of the skeletons so far found is complete, it is assumed that he buried certain bones of the dead in different places from the rest. This burial custom, which is found among primitive peoples in other parts of the world, suggests the conclusion that the Peking Man already had religious notions. We have no knowledge yet of the length of time the Peking Man may have inhabited the Far East. His first traces are attributed to a million years ago, and he may have flourished in 500,000 B.C.

The first remnants of the Peking Man were already found in the 1920s. Only in recent years, remnants of this race were found also in other parts of northern China.

In a later phase of the Pleistocene remnants of a different human race, perhaps related to the Neanderthal race of Europe and Western Asia, have recently been discovered, and the more developed stone scrapers and other implements show some relation to Aurignacian and Mousterian tools of the West. However, it is still much too early to state whether such similarities are the result of transmission or of pure chance.

Finally, in the last part of the Pleistocene, a modern race of Homo sapiens is found in China, first in the upper levels of the Chou-k'ou-tien caves, then in other parts of China; with him appear still further refined and specialized stone tools. Archaeologists are of the opinion that this Far Eastern race may be the ancestor of the Mongoloid races of the northern Far East, but at the same time also the ancestor of a Negroid Oceanic race. Such dark-skinned races are found in parts of the Malay peninsula and the Philippines, as well as in New Guinea. And there are literary allusions in Chinese texts suggesting that a dark-skinned race may once have lived in historical periods in some parts of south China.

Possibly, this new race, which certainly is the ancestor of still existing races, may have developed in the Far East from an earlier Neanderthal race, which again could have developed from the Peking Man race. In any case, none of these earlier human beings has survived anywhere. With the beginning of the ‘recent period’ of geological time, the separation of the Mongoloid and the Negroid race seems to have taken place. Yet the skeletal remains found in An-yang and dating somewhat before the year 1000 B.C. seem to indicate that, at least at that time, still other races may have lived in the area of China.

At the beginning of this ‘recent period’ we find in the Ordos area and north of it a microlithic culture, i.e. a culture in which stone implements of very small size, but well made, were used; similar cultures have also been discovered in the West. At probably the same time, a distinct mesolithic culture appears in the area of the south of China, roughly the area around Canton and west of it. It seems that these people were largely fishers living along the rivers and the coast. It is here that the earliest remnants of a simple, cord-marked pottery have been found. The use of cord indicates that fibres were used, and it is likely that these fishermen already made a kind of bark-cloth by beating fibres from trees into a vegetable felt. This is perhaps one of the most important human inventions, as it may have led to the invention of felt among animal breeders and to the invention of paper and printing many, many centuries later. And it may be that in this southern culture, the first experiments with the cultivation of plants were made. Rice, the staple food of the Chinese, seems to have been cultivated somewhere in South-East Asia; some archaeologists believe in Thailand, others seem to prefer south China. As far as we know, the population of both areas was closely related. Similarly, the cultivation of taro and yam must have begun in the same area.

It is different, however, with those plants which are still typical for the north. It is more generally assumed that wheat and millet came to the Far East from the West, the ‘Fertile crescent’ or even the eastern parts of Africa. Together with these plants came cattle and sheep.

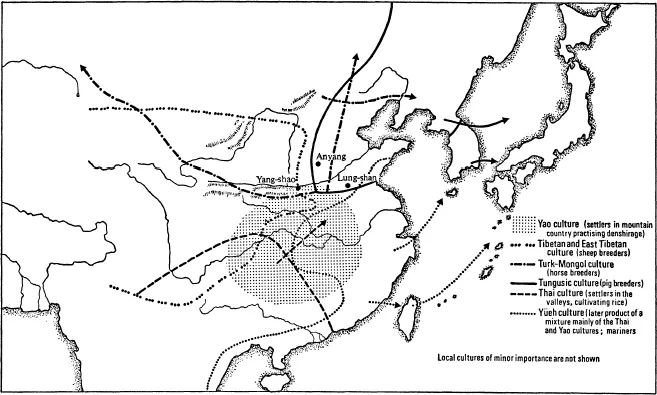

3The eight basic cultures

The principal drawback of archaeology is that what can be excavated is only a small, select section of the total culture of a society. Occasionally, we can draw conclusions from the findings on the religion and the social organization of the people. Thus, even in areas in which archaeologists have done very much work, it often remains impossible and usually questionable to assign to a specific layer that the archaeologists have established, a specific culture which is known from historical accounts to have lived in that same area. Because of the selectivity of archaeological findings, cultures seem to be very much alike over large areas in which numerous different types of societies may have existed. If later archaeologists were to excavate sites of our present time, and if they did not find written documents, they might easily conclude that there was a unified culture all over the world, because they would find the same automobiles, airplanes, radios and televisions everywhere. Here, historical ethnology may come to help. By carefully mapping the distribution of elements of material and non-material culture, by using legends and other traditions, and by tracing the distribution of still existing ‘local cultures’ as far back as possible, it seems possible to establish that in the area which is now China, a considerable number of different, local cultures existed, each developing along its own lines, but finally all contributing in different degrees to the formation of what we then begin to call ‘Chinese culture’. We will mention only the most important local cultures.

(a) The north-east culture, centred in the present provinces of Hopei (in which Peking lies), Shantung, and southern Manchuria. The people of this culture were ancestors of the Tunguses, probably mixed with an element that is contained in the present-day Paleo-Siberian tribes. These men were mainly hunters, but probably soon developed a little primitive agriculture and made coarse, thick pottery with certain basic forms which were long preserved in subsequent Chinese pottery (for instance, a type of the so-called tripods). Later, pig-breeding became typical of this culture.

(b) The northern culture existed to the west of that culture, in the region of the present Chinese province of Shansi and in the province of Jehol in Inner Mongolia. These people had been hunters, but then became pastoral nomads, depending mainly on cattle. The people of this culture were the tribes later known as Mongols, the so-called proto-Mongols. Anthropologically they belonged, like the Tunguses, to the Mongol race.

(c) The people of the culture farther west, the north-west culture, were not Mongols. They, too, were originally hunters, and later became a pastoral people, with a not inconsiderable agriculture (especially growing wheat and millet). The typical animal of this group soon became the horse. The horse seems to be the last of the great animals to be domesticated, and the date of its first occurrence in domesticated form in the Far East is not yet determined, but we can assume that by 2500 B.C. this group was already in possession of horses. The horse has always been a ‘luxury’, a valuable animal which needed special care. For their economic needs, these tribes depended on other animals, probably sheep, goats, and cattle. The centres of this culture, so far as can be ascertained from Chinese sources, were the present provinces of Shensi and Kansu, but mainly only the plains. The people of this culture were most probably ancestors of the later Turkish peoples. It is not suggested, of course, that the original home of the Turks lay in the region of the Chinese provinces of Shensi and Kansu; one gains the impression, however, that this was a border region of the Turkish expansion; the Chinese documents concerning that period do not suffice to establish the centre of the Turkish territory. Recent linguistic research has made it likely that Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic languages are to some degree related and may have developed from one single type of language; it seems also that the Korean language is related to these languages, while Japanese may have more complex origins, though still be related to Korean and through it to the Altaic languages.

(d) In the west, in the present provinces of Szechwan and in all the mountain regions of the provinces of Kansu and Shensi, lived the ancestors of the Tibetan peoples as another separate culture. They were shepherds, generally wandering with their flocks of sheep and goats on the mountain heights.

(e) In the south we meet with four further cultures. One is very primitive, the Liao culture, the peoples of which are the Austro-asiatics already mentioned. These are peoples who never developed beyond the stage of primitive hunters, some of whom were not even acquainted with the bow and arrow. Farther east is the Yao culture, an early Austronesian culture, the people of which also lived in the mountains, some as collectors and hunters, some going over to a simple type of agriculture (denshiring). They mingled later with the last great culture of the south, the Thai culture, distinguished by agriculture. The people lived in the valleys and mainly cultivated rice. The centre of this Thai culture may have been in the present provinces of Kuangtung and Kuangsi. Today, their descendants form the principal components of the Thai in Thailand, the Shan in Burma and the Lao in Laos. Their immigration into the areas of the Shan States of Burma and into Thailand took place only in quite recent historical periods, probably not much earlier than A.D. 1000.

Finally there arose from the mixture of the Yao with the Thai culture, at a rather later time, the Yüeh culture, another early Austronesian culture, which then spread over wide regions of Indonesia, and of which the axe of rectangular section became typical. Linguistically, the languages of the Tibetans (to which minorities in China proper, like the Lolo, belong) are related to the Chinese language. The Thai languages are even closer relatives of the Chinese, while the languages of the Yao and Yüeh seem to have been related to the languages of Indonesia and the South Pacific. The Liao may have relatives in Mon and Kmer cultures of South-East Asia.

Thus, to sum up, we may say that, quite roughly, in the middle of the third millennium we meet in the north and west of present-day China with a number of herdsmen cultures. In the south there were a number of agrarian cultures, of which the Thai was the most powerful, becoming of most importance to the later China. We must assume that these cultures were as yet undifferentiated in their social composition, that is to say that as yet there was no distinct social stratification, but at most beginnings of class-formation, especially among the nomad herdsmen. This picture of prehistoric cultures, each of which is a contributor in its own way to the later ‘Chinese’ culture, is much more detailed than the picture gained from archaeology alone, but is, in my opinion, not in contradiction to the results of archaeology. Doubtless further research will clarify and correct this reconstruction of the last period of Chinese prehistory.

MAP 1Regions of the principal local cultures in prehistoric times

4The Yang-shao culture

The various cultures here described gradually penetrated one another, especially at points where they met. Such a process does not yield a simple total of the cultural elements involved; any new combination produces entirely different conditions with corresponding new results which, in turn, represent the characteristics of the culture that supervenes. We can no longer follow this process of penetration in detail; it need not by any means have been always warlike. Conquest of one group by another was only one way of mutual cultural penetration. In other cases, a group which occupied the higher altitudes and practised hunting or slash-and-burn agriculture came into closer contacts with another group in the valleys which practised some form of higher agriculture; frequently, such contacts resulted in particular forms of division of labour in a unified and often stratified new form of society. Recent and present developments in South-East Asia present a number of examples for such changes. Increase of population is certainly one of the most important elements which lead to these developments. The result, as a rule, was a stratified society being made up of at least one privileged and one ruled stratum. Thus there came into existence around 2000 B.C. some new cultures, which are well known archaeologically. The most important of these are the Yang-shao culture in the west and the Lung-shan culture in the east. Our knowledge of both these cultures is of quite recent date and there are many enigmas still to be cleared up.

The Yang-shao culture takes its name from a prehistoric settlement in the west of the present province of Honan, where Swedish investigators discovered it. Typical of this culture is its wonderfully fine pottery, apparently used as gifts to the dead. It is painted in three colours, white, red, and black. The patterns are all stylized, designs copied from nature being rare. This pottery is still handmade; the potter's wheel is a later invention. Together with this fine pottery, a common grey pottery was still used, and some scholars think that the painted pottery may be a dev...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Maps

- Introduction

- Chapter I: Prehistory

- Chapter II: The Emergence of Feudalism (c. 1600-1028 B.C.)

- Chapter III: Mature Feudalism (c. 1028-500 B.C.)

- Chapter IV: The Dissolution of the Feudal System (c. 500-250 B.C.)

- Chapter V: Military Rule (250-200 B.C.)

- Chapter VI: The Early Gentry Society (200 B.C.-A.D. 250)

- Chapter VII: The Epoch of the First Division of China (A.D. 220-580)

- Chapter VIII: Climax and Downfall of the Imperial Gentry (A.D. 580-950)

- Chapter IX: Modern Times

- Chapter X: The Period of Absolutism

- Chapter XI: The Republic (1912-1948)

- Chapter XII: Present-day China

- Notes and References

- Index