eBook - ePub

Forming Entrepreneurial Intentions

An Empirical Investigation of Personal and Situational Factors

- 148 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forming Entrepreneurial Intentions

An Empirical Investigation of Personal and Situational Factors

About this book

This book examines the relationship between a person's intentions to start a business and specific personal and situational factors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forming Entrepreneurial Intentions by David F. Summers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

Introduction

The need to understand entrepreneurship has never been more important than it is today (Bygrave, 1993, p.256). In the United States alone, entrepreneurial activity accounts for 38 percent of the gross domestic product and 40 to 80 percent of all new jobs (Dennis, 1993). This significant economic impact has fueled the current interest in research of the entrepreneurial phenomenon.

In spite of growing interest in entrepreneurship, little consensus exists among researchers concerning entrepreneurial theories, definitions, and research directions (Bull & Willard, 1993; Carland, Hoy, & Carland 1988; Gartner, 1988; Wortman, 1987). One explanation is that entrepreneurship is a multi-faceted phenomenon that crosses many academic disciplines (Low & MacMillian, 1988). Regardless of the complexity of the phenomenon or research debate, the importance of entrepreneurship demands research attention.

Early research into entrepreneurship and the individual decision to become an entrepreneur has focused primarily on “who entrepreneurs are” (trait approach) or “what entrepreneurs do” (behavior approach) (Gartner, 1988). For example, Boyd and Vozikis (1994) point out that such traits as McClelland’s (1961) need for achievement, locus of control (Brockhaus, 1982), risk-taking propensity (Brockhaus, 1980), and tolerance for ambiguity (Schere, 1982) have been associated with entrepreneurship. On the other hand, Gartner (1988) argues that individual traits are ancillary to the entrepreneur’s behavior. The focus, therefore, should be on what the entrepreneur does and not who the entrepreneur is. Research by Herbert and Link (1982) and Shapero (1982) has taken a more behavioral approach in explaining how entrepreneurship occurs by focusing on the activities of entrepreneurship (e.g., opportunity recognition, gathering resources). Neither the trait nor the behavior approach alone, however, fully explains the complexity of the entrepreneurial phenomenon.

In an attempt to combine the trait and behavior approaches, expand the research arena, and more accurately capture the complexity of entrepreneurship, researchers have presented comprehensive flow models of the venture creation process (i.e., Behave, 1994; Gartner, 1985; Martin, 1984; Moore, 1986; Vesper, 1980). These process models include a series of critical entrepreneurial behaviors such as opportunity recognition (Behave 1994; Krueger, 1989), firm initiation (Behave, 1994; Martin 1984; Moore, 1986; Shapero, 1982), and firm growth (Moore, 1986). Also included in these models is the influence of personal traits such as those previously mentioned: need for achievement, locus of control, risk taking propensity, and tolerance for ambiguity. Finally, these models consider the roles that personal characteristics (e.g., age, education, gender, minority status) along with social influences (e.g., role models, parents, family, community) and environmental factors (e.g., government influence, capital availability, competition) play in the entrepreneurial process (Gartner, 1985; Martin, 1984; Matthews & Moser, 1996; Moore, 1986).

Regardless of the comprehensiveness or the complexity of the entrepreneurial model, organizations are founded by individuals who make the critical cognitive decision to start the business (Learned, 1992). Each of these individuals brings an accumulation of unique combinations of background and disposition that trigger the decision to start or abort the whole idea of starting a business (Naffziger, Hornsby, & Kuratko, 1994). Not all individuals have the potential for entrepreneurship, and of those who do, not all will attempt the process. Of those who attempt, not all will be successful (Learned, 1992). Therefore, the primary element of entrepreneurship is the critical combination of the individual, his or her past experience, background, and the decision to start an enterprise.

Learned (1992) developed a framework of the founding process that includes the consideration of the individual and his or her experience and background. He proposed that the founding process has four primary dimensions: 1) propensity to found, 2) intention to found, 3) sense making, and 4) the decision to found. Propensity to found suggests that some individuals have a combination of psychological traits that interact with background factors to make them likely candidates to attempt to start a business. Intention to found posits that some individuals will encounter situations that will interact with their traits and backgrounds to cause the intention to start a business. Sense making implies that intentional individuals interact with the environment while attempting to gather resources and make their business a reality. As a result, intentioned individuals will ultimately make the decision to start a business or abandon the attempt to start depending upon the sense made of the attempt (Learned, 1992).

Critical to Learned’s (1992) process is the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. In addition, as Learned (1992) suggested, the formation of intentions is the result of the interaction of psychological traits and background experiences of the individual with situations that are favorable to entrepreneurship. Therefore, the focus of this study is to develop a model that explains the unique combination of the individual entrepreneur and his or her experiences and background that ultimately leads to the formation of entrepreneurial intentions to start a business.

STATEMENT OF PROBLEM

Intentions have been clearly demonstrated to be the single best predictor of planned behavior (Krueger, 1993). Considering the fact that new entrepreneurial organizations emerge over time as a result of careful thought and action, entrepreneurship is an example of such planned behavior (Bird, 1988; Katz & Gartner, 1988). In addition, entrepreneurship is a process that does not occur in a vacuum but is influenced by a variety of cultural and social factors as well as personal traits and characteristics (Reynolds, 1992). Intentions-based process models are able to capture the complexity of entrepreneurship and provide a framework to build robust, testable process models of entrepreneurship (Krueger, Reilly, & Carsrud, 1995; MacMillian & Katz, 1992).

Researchers have developed several intentions-based models of planned behavior and entrepreneurship such as the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980) and Shapero’s (1982) model of the entrepreneurial event. Expansions and revisions of intentions models have been proposed by Bird (1988) and Boyd and Vozikis (1994). Despite the interest in intentions-based models, few studies explicitly use theory-driven intentions-based process models of entrepreneurship (Gartner, 1988; Mac-Millian & Katz, 1992). Fewer still include theory-based models of entrepreneurial intentions (Krueger, et al., 1995). The lack of research using intentions-based models is interesting considering that these models have the potential to address the critics of entrepreneurship research who decry that models built from censored samples and from “20–20” hindsight produce spurious results and explanations (Krueger et al., 1995). Therefore, the current study uses an intentions-based model to answer the following research question: “What personal and situational factors relate to the formation of entrepreneurial intentions?”

PURPOSE OF STUDY

The study was designed to be a theory-building effort in which the relationships among the personal traits and characteristics of the entrepreneur along with predisposing events can be examined for their relationship with the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. The study focused on using a theoretically sound intentions-based process model of entrepreneurship that includes traits and characteristics of the entrepreneur along with predisposing events. The results are used as the first step in predicting entrepreneurial behavior.

The following section provides an overview of the literature that constitutes the theoretical foundation for the study. Work done on previous intentions-based models of entrepreneurship plus research conducted in contexts outside entrepreneurship provide the basis for the research model.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

Central to entrepreneurship is the ultimate decision of the entrepreneur to start the enterprise. Learned (1992) described the starting, or as he put it the founding, process as having four dimensions -1) propensity to found, 2) intention to found, 3) sense making, and 4) the decision to found. Some individuals have a combination of psychological traits that interact with background factors that give them a propensity to found and, thus, become likely candidates to attempt to start a business. Not all individuals with a propensity to found, however, will develop the intentions to found. Only when individuals encounter situations positively that interact with their traits and background factors, will they develop the intentions to found. Not all intentioned individuals will make the final decision to found. Sense making implies that intentioned individuals interact with the environment while attempting to gather resources and make the business a reality. As a result, intentioned individuals will ultimately make the decision to start a business or abandon the attempt depending upon the sense made of the attempt (Learned, 1992). Based on the discussion of Learned’s framework, the formation of entrepreneurial intentions is critical to making the final decision to found the business. Therefore, intentions-based models of entrepreneurship hold significant potential to explain the early entrepreneurial process, even before the firm emerges (Bird, 1992; Carsrud & Krueger, 1995; Katz & Gartner, 1988; Krueger & Brazeal, 1994).

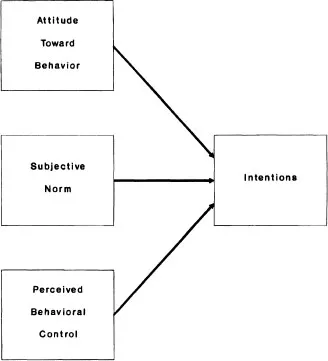

The theoretical foundation of the research study is rooted in Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior (see Figure 1) (Ajzen 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The theory of planned behavior suggests that behavior is predicted by behavioral intentions, which are a function of individual attitudes toward the behavior, a subjective norm, and perceived behavior control (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Individual attitudes are a person’s overall evaluation of whether performing the behavior is good or bad (Ajzen, 1991). A subjective norm is a person’s belief that people who are important to the person think that he or she should, or should not, perform the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Finally, perceived behavioral control is an individual’s judgement of the likelihood of successfully performing the intended behavior (Ajzen, 1991).

Subsequent testing of the model has supported its validity by demonstrating the ability of intentions to predict behavior in a variety of situations (e.g., Ajzen, 1991; Doll & Ajzen, 1990; Nettemeyer, Andrews, & Durvasula, 1990; Schifter & Ajzen, 1985). In fact, research suggests that intentions are the single best predictor of planned behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Krueger et al., 1995). Entrepreneurship is clearly planned behavior (Krueger et al., 1995). Therefore, the formation of entrepreneurial intentions holds significant potential to predict entrepreneurial behavior.

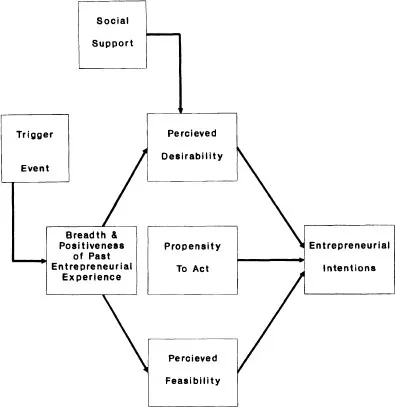

Shapero (1982) extended the focus on intentions by developing an intentions-based model of the entrepreneurial event (see Figure 2). Like Ajzen, Shapero theorized that a person’s intentions of starting a business would accurately predict his or her engaging in entrepreneurial activity (Shapero, 1982). He further suggested that the direct antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions consisted of the perceived desirability of starting a business, a person’s perception of the feasibility of starting a business, and a person’s propensity to take action (Krueger, 1993; Shapero, 1982). Shapero (1982) also suggested that the extent of past exposure to entrepreneurship (breadth) and an evaluation of the positiveness of the past experiences influence perceptions of desirability and feasibility (Krueger, 1993).

Figure 1. Ajzen’s (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior

The perceived desirability of entrepreneurial activity is influenced by social forces, especially those forces of family and friends (e.g., Bird, 1988; Bygrave, 1997; Martin, 1984). Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) also provide support for this assertion by suggesting that the attitudes that help form intentions are influenced by what people (i.e., family, friends) who are important to the person forming the intentions think. Therefore, the literature suggests that the social influence of family and friends, or social support, impact the formation of entrepreneurial intentions.

Figure 2. Shapero’s (1982) Model of the Entrepreneurial Event

Perceived feasibility is defined as “. . . the degree to which one believes that he or she is personally capable of starting a business” (Krueger, 1993 p. 8). Perceptions of feasibility appear closely related to the construct of perceived self-efficacy (Ajzen, 1991, 1987) as theorized in Bandura’s social learning theory (Bandura, 1977). Self-efficacy is a comprehensive summary or judgement of a person’s perceived capability of performing a specific task (Gist & Mitchell, 1992). Previous research has shown that self-efficacy predicts motivation and task performance in a variety of work-related situations (Gist, 1987) such as sales for insurance agents (Barling & Beattie, 1983), career choice (Lent, Brown, & Larkin, 1987), and adaptability to new technology (Hill, Smith, & Mann, 1987). Therefore, as suggested by Boyd and Vozikis (1994), self-efficacy is useful in explaining the process of evaluation and choice that surrounds the development of entrepreneurial intentions.

Gist and Mitchell (1992) suggested that perceptions of self-efficacy are determined by three types of assessments. First, there is an analysis of task requirements, which requires an individual to develop inferences about what it takes to perform the required task at various levels of performance. Second, individuals make an assessment of personal and situational resources and constraints. Third, individuals attribute past experiences of success or failure to the task to be performed (Gist & Mitchell, 1992).

Applying the three assessments to entrepreneurial behavior would suggest that individuals would first development inferences about what it takes to start a business such as opportunity recognition, writing a business plan, and obtaining financing. Next, the individual would assess his or her ability to perform the required tasks and the availability of the necessary resources to start a new business. Finally, the individual would draw on either positive or negative past entrepreneurial experience to help formulate his or her perceptions of the chances of successfully starting a new business....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Chapter I - Introduction

- Chapter II - Literature Review and Development of Research Model and Hypotheses

- Chapter III - Method

- Chapter IV - Results

- Chapter V - Discussion

- Appendix

- References

- Index