![]()

1 | THE DREAM: SEAMACH ENGINEERING* |

Case A

In April 1979, Alan Sealey felt that he was finally in a position to leave his present employer and start the first phase to set up his own company which would offer sub-contract machining facilities to the engineering industry. This case outlines his thoughts at that time.

It has been my ambition to start my own company for a number of years, and I have spent these past years trying to accumulate sufficient capital to launch such an operation.

Having left school just before the age of 16, I served an apprenticeship as a turner in a small engineering company in Bath. I was employed in a medium-to-heavy engineering environment and involved in the manufacture of pumps, dockside cranes, deck machinery, construction equipment and, more recently, the offshore cranes used on oil rigs in the North Sea.

Throughout my apprenticeship I attended day-release classes at the local technical college where I gained a craft certificate to City and Guilds standard (passed with credit), but by the end of my apprenticeship I had become disillusioned about my future prospects. Though I enjoyed turning as a job, it was obvious to me that I would never get full satisfaction from it whilst working for someone else. I had my own ideas on the best way to run a machining operation and the type of equipment required to be successful, which were different from those of the companies I worked for. Perhaps the best way of giving you an idea of my opinions regarding areas for improvement in engineering today is to show you an article (see Appendix 1.3) from the Guardian which was based on an interview which I gave over the telephone as a result of a letter I had published in The Financial Times.

As I knew of nobody who would be in a position to finance me I had to rely on my own capacity to save. The best option open to me at that time appeared to be the merchant navy, and so I joined Shell Tankers (UK) Ltd, as a fifth engineer. I stayed with them for just over twelve months. However the job was too career-structured to enable me to make any money in the short term and I also felt too far removed from the manufacturing environment to which I had become accustomed.

Having left Shell Tankers in 1975, I returned to my previous employer who in the meantime had started a nightshift in the machine shop. This seemed to offer me the opportunity of building up my capital base and so I started on the nightshift as a turner in May 1975 and soon gained the top skilled rate as a turner. Indeed, I was the youngest skilled turner to be in that position. I also increased my saving power where possible by investing on the Stock Exchange with which I had some success.

I have now served a four-year period of nights, and it is obvious to me that the method of running the machine shop has deteriorated still further and that the waste of resources, both manpower and machines, is something that I cannot work with any longer. Though I voiced my opinions to management in what I consider to be a constructive attitude, I have been unable to obtain any satisfaction whatsoever and now face the prospect that I may become thought of as a professional moaner. It is under these conditions that I am considering the offer of two friends to go into partnership as property developers. We bought a cottage at the beginning of 1979 and spend weekends and evenings renovating it. However, it is a very slow process and I feel that if I were to work full time on the project, by the autumn we would be able to sell the cottage and I would have enough capital to start my machining business.

Unfortunately the capital which I will have (about £7,000) will not be enough for my original intention which was to base my machining facility on the new generation of CNC [Computer Numerically Controlled] machine tools. Perhaps I should explain the relevance of machine tools in engineering. It is probably best summed up by saying that the machine tool is to engineering what the loom is to textiles. By the new generation of machine tools I refer to machines that are completely programmable for particular jobs. Rather than being controlled by an operator they are run by a pre-programmed tape via a control centre which for all intents and purposes is a computer. It is possible to run each tape through each machine’s individual control system or run a number of machines from one central control. These machines are being developed on a continuing bases with the advent of the micro-chip. They offer great advantages, such as increases in productivity, elimination of operator errors and reduced labour needs for higher output. Up to the present time these machines have been mainly suitable for large production runs of particular components but advances in design are enabling them to be used for much reduced volumes of any one component.

However, as one would expect, the capital costs of starting a facility based on this technology are substantial! I anticipate between £50,000 and £100,000. It is for this reason that I am unable to start my subcontract facility with machines of this calibre. Bearing this in mind I intend to start my facility with the best second-hand machines that I can get for the capital I have. I propose to start by buying two basic machine tools, namely a centre lathe and a vertical borer plus auxiliary machines such as tool and drill grinders costing about £10,000 in total. [An example of this innovation is attached as Appendix 1.1.] These machines will enable me to obtain sub-contract work from various engineering companies in the light to medium range. To give myself a competitive edge I am considering the possibility of adding suitable automation processes to these machines such as now exist on the market. [I anticipate my total start-up costs to be around £20,000.] Updating of basic machine tools looks feasible when compared with the outlay required for purpose built machines of the type mentioned previously. It is my intention, once established, to move into completely automated machines wherever possible, as the growth of my company allows.

The market I am particularly interested in sub-contracting to is the aerospace industry, for example, Rolls Royce. This market appears to me to give the most opportunity for growth over the next decade. Providing I can obtain suitable premises in my own area of Bath, I shall in the first instance approach my previous employer and a number of other firms in the area for work. By establishing myself in this way it will enable me to approach firms such as Rolls Royce, hopefully having gained a reputation for quality work, good delivery times and price.

If it proves impossible for me to obtain premises in my local area I shall look at the possibility of moving to a development area elsewhere in the British Isles, though I would need to investigate each proposal carefully to ensure that I would not become isolated from potential customers.

I shall not be employing anyone at the outset of my business though I hope to employ someone on a part-time basis from December in the first year to enable me to keep up machining time whilst acquiring further business.

I cannot stress strongly enough my belief that the use of the new generation of high technology machine tools represents the best opportunity for the engineering industry in this country to recapture its home market, from which it will once again be able to compete successfully in the world market. We simply must get back to making things competitively, rather than acting as a consumer to the rest of the world. In my own case, by using this new technology, I intend to establish a ‘centre of excellence’ in machining.

DISCUSSION POINTS

Case A – | This case should start the discussion of the skills and goals necessary to start a business. In particular: – What skills does Alan Sealey appear to have? – How realistic is he about the market? – What problems might he face in realising his dream? |

Appendix 1.1: Extract from The Financial Times 7 March 1978

TALISMAN describes equipment by Toolmasters Controls for automating basic machine tools – lathes, drills and mills in a most simple and inexpensive way. The technology has been kept unsophisticated, and it can be adapted to fit either new or existing equipment.

Both single and multiple work-pieces can be produced. In the case of multiples, as the operator makes the first piece, all the movements of the machine are recorded on a magnetic tape cassette. When played back, this will reproduce exactly all the machine movements, without the inevitable delays which result if drawings or charts have to be interpreted.

Talisman can control not only the basic machine movements but also the spindle, coolant, clamps, copy slides, rotary indexing table, indexing tool posts – in all, up to eight auxiliary functions can be controlled.

Individual display modules show the position of each machine axis, and control its movements. Each module has two interdependent counters which indicate either the position from an absolute datum point or an incremental movement. Pushbuttons, marked with simple arrows, cause the machine to move. The feed-rate of the machine movement is selected by a rotary switch on the display, to give rapid, jog, or controlled feed-rate. The machine moves on a predetermined distance when the required figure is dialled on the thumbwheel switches and the direction button is pressed.

The display modules generate pulses which are fed by way of the cassette recording unit to the motor drives; these provide the power for the stepping motors and drive the screws relating to each machine axis. The cassette recorder registers the pulse trains and also the signals for the auxiliary functions and, on play-back, takes complete control of the machine tool.

Toolmasters Controls, Perimeter Road, Woodley, Reading, Berks RG5 4SX.

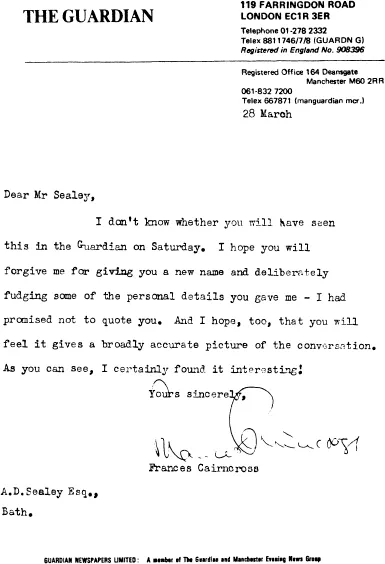

Appendix 1.2: Letter from the Guardian

Appendix 1.3: Article in the Guardian, Saturday March 25 1978

Questions and answers

The most interesting half hour I have spent in the past few days has been on the phone to a young man whom I’ll call Peter. Peter is a 24-year-old turner with a medium-sized engineering firm in the West Midlands.

I rang him because he had written to the newspapers, complaining that while everyone thought that British firms did not invest enough, the real problem was that when they did invest, they made bad buys and used their new machinery inefficiently.

That seemed to me extremely plausible, and I wanted to know how he had reached such a conclusion. After half an hour on the phone, I felt I understood a great deal more about that hoary old question, what’s wrong with British industry. But I also felt perversely optimistic.

The conversation went roughly like this:

Peter: What I was thinking of when I wrote was a new machine tool our firm has just bought. It cost about £80,000. It’s a central lathe-turner, and they bought it to replace an old machine which has been doing the job for 20 years, but is pretty-well worn out.

When the new machine arrived, it turned out it was slower than the old one. At first, the management blamed us, and said it was low productivity. But then they complained to the firm that sold them the machine.

That firm sent a man down to look at it, and he told them it was never intended to do the job they were using it for.

Me: How on earth did they buy it in the first place?

Peter: Well, this is the thing. They sent some chaps up to look at it before they bought it, but they were all from the management – the plant engineer and the planning engineer and so on. There were none of the operators who were actually going to use it. They would have been able to see the snags.

We have a committee which talks about new machines, but only after they have been ordered. Now of course the management have admitted they bought the wrong machine.

Me: Perhaps part of the problem is the kind of people who go into middle management. In some firms the typical works manager seems to be an older chap who wants steady hours and who doesn’t have any particular management talent.

Peter: The trouble in our firm is that the people who get promoted from the shop floor are never the ones with high productivity. They’d rather anyone who was productive stayed on a machine. Of course, a lot of them don’t mind, because if you get promoted to the planning office you earn less money at first. But the younger chaps do want to get into planning office jobs because they see it as a stepping stone to promotion.

Me: How did you come into engineering?

Peter: I did my four years’ apprenticeship here. Then I did a year in the merchant navy. I’ve been back here for four years now.

Me: Why do you think that more school-leavers don’t want to go into engineering?

Peter: I don’t think the firms take enough trouble about their image. Engineering can be the most exciting thing in the world. But the firms never try to tell people that. Take my firm. At the moment, it’s making a new kind of floating dock which is going to replace the ordinary dry dock for ships....