![]()

Leisure Constraint Theory and Sport Tourism

Tom Hinch, Edgar L. Jackson, Simon Hudson & Gordon Walker

T.D. Hinch, Faculty of Physical Education and Recreation, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Correspondence to:

[email protected]Introduction

Despite a flurry of recent publications, sport tourism is still in its infancy as an area of academic investigation. As such, it is characterized by ideographic studies which have merit in terms of specific situations but which have had limited success in advancing the field in a systematic manner. This fact leaves the area open to academic criticism based on the prevalence of descriptive rather than explanatory or predictive research. The broader field of leisure research has faced similar censure but has countered it by adapting theories used in other realms to help drive leisure research agendas. Leisure studies researchers have also introduced unique theoretical approaches that have advanced the field. One such theoretical approach focuses on leisure constraints.

Leisure constraints have been defined as 'factors that are assumed by researchers and/or perceived or experienced by individuals to limit the formation of leisure preferences and/or to inhibit or prohibit participation and enjoyment in leisure’ [1]. Researchers would be well served by using constraints-based approaches to drive research questions related to sport tourism. In doing so, insight could be gained as to why sport tourists behave in certain ways and, by extension, why the sport tourism industry is characterized by its own unique idiosyncrasies.

Areas of Constraint in Sport Tourism

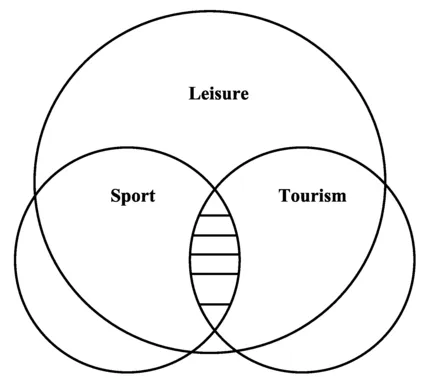

Leisure, sport and tourism are closely related concepts (Figure 1). For the purposes of this discussion, leisure is considered in a broad sense as:

that portion of an individual’s time that is not directly devoted to work or work-connected responsibilities or to other obligated forms of maintenance or self-care. Leisure implies freedom and choice and is customarily used in a variety of ways, but chiefly to meet one’s personal needs for reflection, self-enrichment, relaxation, or pleasure. While it usually involves some form of participation in a voluntarily chosen activity, it may also be regarded as a holistic state of being or even a spiritual experience [2].

In defining sport as 'a structured, goal-oriented, competitive, contest-based, ludic physical activity' [3], it is clearly situated as a subset of leisure. One possible exception is professional sport, although the spectator consumption of this activity clearly falls within the parameters of leisure. Tourism, in turn, can be defined as 'the travel of non-residents to destination areas as long as their sojourn does not become a permanent residence' [4]. While business travel falls outside of the leisure concept, pleasure-based travel is clearly a form of leisure and in this paper, tourism refers to leisure-based travel [5]. The spheres of sport and tourism also converge within the realm of leisure and it is this shaded area in Figure 1 that provides the context for this discussion on constraints.

Figure 1 The Relationship between Leisure, Sport and Tourism.

Although sport tourism is a relatively new concept in terms of contemporary academic vernacular, its scope of activity is far from a recent phenomenon. The notion of people travelling to participate and watch sport dates back to the ancient Olympic Games and, in modern times, the practice of stimulating tourism through sport has existed for over a century Within the last few decades, however, the tourism industry has more fully realized the significant potential of sport tourism and is aggressively pursuing this market niche. Broadly defined, sport tourism includes travel away from one's primary residence to participate in a sport activity for recreation or competition, travel to observe sport at the grassroots or elite level, and travel to visit a sport attraction such as a sports hall of fame or water park [6]. From an attraction perspective, sport tourism has been defined as 'sport based travel away from the home environment for a limited time where sport is characterized by unique rule sets, competition related to physical prowess and a playful nature' [7]. In both cases, it is clear that there are constraining forces that can limit an individual's travel behaviour associated with attending sport events, actively engaging in sporting activities away from the home environment or visiting distant sport heritage sites.

From a constraints perspective, the fundamental question is why do some people not participate in sport tourism activities or not participate to the extent that they may desire? One of the obvious answers to this question includes geographic factors. By definition, tourism requires travel between home communities and the tourist destination. The more isolated the destination or the longer the distance to a destination, the greater the constraint [8]. While not specifically couched in the terminology of constraints, geographers have articulated this idea through the development of distance decay theory which highlights the inverse relationship between increasing distance and the number of travellers visiting a destination [9]. Beyond this fundamental constraint of tourism, there exists a broad range of other constraints. Initial insight into the nature of these constraints can be gained by considering them within the context of: (1) typologies of sport tourism activity; (2) sport attraction frameworks; and (3) the interface of the sport and the tourism delivery systems.

Activity Typologies

A typology developed by Gibson highlights three distinct realms of sport tourism activities: event-based activities, active participation, and nostalgia-based sport travel [10]. Event-based activities are epitomized by major sporting festivals such as the Olympic Games but also include a broad range of large-, medium- and small-scale events. The distinguishing feature of this category in terms of constraints is that the focus is on the spectators at these events. Those things that discourage or prevent potential spectators from travelling to the event need to be considered. Perceptions of crowding or price-gouging represent two possible constraints. Active sport tourism refers to sport activities characterized by the physical involvement of the tourist directly in the sport. Golfers and downhill skiers are two examples of sport tourists falling into this category. In contrast to more sedentary spectators at sporting events, active sport tourists may face a broader range of physical constraints associated with fitness and health. Nostalgia sport tourists include those who travel to venerate sporting facilities and museums, along with the growing number of tourists visiting fantasy sport camps where they can be transported back to their youth or mingle with their sporting heroes. While nostalgia sport tourists may share a variety of constraints with their event and active counterparts, they are more likely to be constrained by lower levels of supply and perhaps by lack of awareness about existing opportunities.

Attraction Systems

Leiper’s attraction system can also be used to suggest the nature of constraints in sport tourism [11]. While the idea of sport as a tourist attraction is not new [12], the theoretical basis of sport as a tourist attraction is just beginning to be addressed in a systematic fashion [13]. Leiper defines a tourist attraction as ‘a system comprising three elements: a tourist or human element, a nucleus or central element, and a marker or informative element. A tourist attraction comes into existence when the three elements are connected’ [14]. Leisure constraints may be found within each of these components. Given the interdependent nature of the attraction system, a constraint in any one of its components is likely to compromise the empirical relationship, thereby diminishing the attraction’s capacity.

The first component of Leiper’s attraction system is the human element [15]. The tourist or human element consists of persons who are travelling away from home to the extent that their behaviour is motivated by leisure-related factors. Five assertions are made about the nature of this behaviour:

First, the essence of touristic behaviour involves a search for satisfying leisure away from home. Second, touristic leisure means a search for suitable attractions or, to be more precise, a search for personal (in situ) experience of attraction systems’ nuclear elements. Third, the process depends ultimately on each individual’s mental and nonmental attributes such as needs and ability to travel. Fourth, the markers or informative elements have a key role in the links between each tourist and the nuclear elements being sought for personal experience. Fifth, the process is not automatically productive, because tourists’ needs are not always satisfied (these systems may be functional or dysfunctional, to varying degrees) [i.e., constraints] [16].

Examples of sport tourists include athletes, spectators, coaches, officials, media and an assortment of other groups for whom sport is an important part of their travel experience. Each of these groups faces their own unique set of constraints. Competitive athletes, for example, often have to qualify for competition based on performance measures.

The second major element of the tourist attraction system is the nucleus, which refers to the site where the tourist experience is produced and consumed. More specifically, in the context of sporting attractions, the attributes of the sporting activity make up the nucleus of the attraction [17]. In the case of sport tourism, this nucleus is determined by unique rule sets, competition related to physical prowess, and the ludic nature of a featured sport. Constraints may be embedded explicitly in the rules, in the competitive nature of the sport, and the type of physical prowess required. These constraints may also be imbedded in the ludic nature of the sport related to whether it is played at an elite or recreational level. Constraints related to the nucleus may also vary according to attraction hierarchies as perceived by the tourist. Some sport nuclei may serve as the primary attraction for the trip, while others are secondary attractions and still others are incidental or tertiary attractions [18]. Even when faced with a similar constraint (for example, cost of event admission), differing perceptions of the attraction within this hierarchy may mean that the power of the constraint varies substantially among potential visitors.

The third element of the attraction system consists of markers, or items of information about any phenomenon that is a potential nucleus element in a tourist attraction [19]. These markers may be positioned consciously or unconsciously to function as part of the attraction system. Examples of conscious attraction markers featuring sport are common. Typically, they take the form of advertisements showing visitors involved in destination-specific sport activities and events. An even more pervasive form of marker includes televised broadcasts of elite sport competitions and advertisements of non-travel products featuring sports in recognizable destinations. Broadcast listeners and viewers have the location marked for them as a tourist attraction, which may influence future travel decisions. These markers may serve as constraints where they are absent or where, in the case of media coverage, negative destination images are projected.

Interface between Sport and Tourism

Traditionally, the sport system and the tourism system have operated quite separately from each other. Tourism can be described in terms of an integrated system featuring tourists, transportation linkages, destinations (inclusive of attractions, accommodation, hospitality and services), and a marketing component. Fragmentation within these systems can introduce an assortment of supply-based constraints. The sport delivery system is characterized by a variety of public and private stakeholders. While profit-driven professional sports franchises receive much media attention, the vast majority of sport falls under the administration of the not-for-profit volunteer sector. This delivery system tends to suffer budget crises in times of economic restraint and must deal with the limitations as well as the benefits of a large voluntary sector. Limitations include the transitory nature of volunteers, a general lack of formal management training, and the tendency to focus on the performance aspect of the sport at the ex...