![]()

Editorial

Neighbourhood Effects on Social Opportunities: The European and American Research and Policy Context

JÜRGEN FRIEDRICHS, GEORGE GALSTER & SAKO MUSTERD

In contemporary European and American urban policy and politics and in academic research it is typically assumed that spatial concentrations of poor households and/or ethnic minority households will have negative effects upon the opportunities to improve the social conditions of those who are living in these concentrations. Since the level of concentration tends to be correlated with the level of spatial segregation the ‘debate on segregation’ is also linked to the social opportunity discussion. The central question is “Do poor neighbourhoods make their residents poorer?” (Friedrichs, 1998), i.e. does the neighbourhood structure exert an effect on the residents (behavioural, attitudinal or psychological) even when controlling for individual characteristics of the residents?

The issue of neighbourhood effects on social opportunities of residents possesses rich geographical, sociological, economic and psychological dimensions, and as such has offered a locus for multi-disciplinary investigations on both sides of the Atlantic. Such diversity is amply demonstrated in this Special Issue of Housing Studies, with economists, geographers, planners and sociologists, hailing from Germany, the Netherlands, UK and USA, represented among the contributors. These diverse perspectives often intersect in two realms: spatial relationships and selective household mobility.

The spatial focus of neighbourhood effect studies is clear, for example, in economic geographical studies about the spatial mismatch between demand and supply on the labour market (Kasarda et al., 1992). The thesis here is that economic restructuring has led to a situation in which the peripheral locations of suitable jobs for unskilled workers and inner-city residential locations of these potential workers have grown too far from each other to enable matching on a daily basis; this would aggravate the social conditions of those who live in inner-city areas. The spatial element is also evident in the research underpinnings of American housing policy aimed at changing the locations of low-income or minority households (Briggs, 1997; Del Conte & Kling, 2001; Katz et al., 2001; Ludwig et al., 2001; Rosenbaum, 1995; Rosenbaum et al., 2002). These American policies for changing the spatial distribution of the disadvantaged are related to European ideas about ‘mixed neighbourhood policies’ that nowadays receive considerable attention and critiques (Atkinson & Kintrea, 2001; Kearns, 2002; Musterd et al., 1999, Musterd et al., this issue; Ostendorf et al., 2001). As an illustration, in this issue van Beckhoven & Van Kempen address the urban restructuring effects in two Dutch cities, focusing on the social relations and interactions of residents. They conclude that the neighbourhood restructuring plays only a limited part in the life of most of the residents.

Urban researchers from multiple disciplines also intersect each other when they pay attention to selective residential migration processes in relation to neighbourhood effects. One of the crucial issues in this regard is the increasing concentration of poverty in certain areas, which is exacerbated by middle-class households moving out to more affluent neighbourhoods. In many American cities the flight of these households towards suburban neighbourhoods expresses a process of ‘leaving the cities behind’ (cf. Thomas, 1991; Wilson, 1987). As an effect, the service structure in poor inner-city neighbourhoods declines as the local tax base erodes. Vicious circles are expected to develop in extreme cases, implying a clear, pernicious neighbourhood effect. For example, one might start with the development of concentrations of poor inhabitants (frequently poor immigrants or ethnic minorities), followed by an erosion of public facilities and services, residential abandonment and rising crime, lack of opportunities and therefore again the attraction of those with the weakest positions. Racial factors may overlay class factors in creating a dual-feature segregation that intensifies poverty and constrains outward opportunity (Massey & Denton, 1993).

However, the fact that these kinds of mobility processes are encountered in American cities does not imply there are necessarily special neighbourhood effects. In their paper Kearns & Parkes pay attention to mobility in relation to neighbourhoods in the UK context. Their focus is on home and neighbourhood perceptions and residential mobility behaviour. They include poverty, anti-social behaviour and crime as key variables affecting perceptions and mobility. Nevertheless, their conclusion is that there is “no evidence to support the notion of a distinctive culture in deprived UK areas”, rather, “residents in poor areas were responding to negative residential conditions in the same way as the rest of the population”. It is also interesting to see that in several European cities the levels of segregation and separation are much lower compared to American experiences. This may imply that neighbourhood effects are less significant in Europe.

Moreover, unlike the American experience, usually it is not the inner city that collects the largest problems. Instead it is the outer areas, such as the banlieue in Paris (cf. Wacquant, 1993) and other large French cities, or post-war social housing complexes on the fringes in cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin, Glasgow, Stockholm and Naples, which are characterised by serious concentrations of social problems. One factor contributing to such concentrations is the social housing allocation policy in many European cities. In Germany, for example, poor or ‘problematic’ families are allocated to social housing dwellings by non-profit housing associations. These dwellings are predominantly located in the peripheral housing estates, thereby increasing the spatial concentration of distressed households.

In sum, the field of neighbourhood effects and social opportunities is currently an exciting one, characterised by spirited, multi-disciplinary debates. Unfortunately, one set of debates has been conducted within North America and another within Europe, often with little commonality. It is the goal of this Special Issue to bridge this gap, and offer ways of thinking about this issue that will help advance the discussion in both regions. This issue offers four illustrations of exemplary recent European research on neighbourhood effects, followed by two American-authored papers, one by Galster, offering a new methodological strategy and the other by Briggs, who both offers comments on the European papers by putting the neighbourhood effect debate into a dynamic city-wide, nation-wide and global nested framework; and links the European papers to potential policy arenas.

The Editorial now proceeds by providing a Trans-Atlantic overview of the neighbourhood effects debates. Specifically, the review is organised around the questions: How large are neighbourhood effects? How can these effects be measured precisely? How do these effects transpire? Directions for future research on the topic are then suggested.

How Much, How, and How do we Know? A Trans-Atlantic Overview

Neighbourhood effects have been the source of American scholarly enquiries for over half a century. An early manifestation was the discussion on the proper ‘social mix’ of a neighbourhood (e.g. Gans, 1961; Sarkissian, 1976), but in this literature the effect was assumed to exist but not specified nor explored empirically. American empirical interest in the issue arguably was kindled by the seminal work of William Julius Wilson (1987), who claimed that the socially isolated environments of concentrated poverty neighbourhoods encouraged ‘underclass’ behaviours in US cities. Since then there has been a dramatic increase in the number of scholarly studies produced in the USA that investigate the impact of the residential neighbourhood on a variety of outcomes for youth and adults. The burgeoning findings of this multidisciplinary literature have spawned several comprehensive review articles (see especially Briggs, 1997; Ellen & Turner, 1997; Galster, 2002; Galster & Killen, 1995; Gephardt, 1997; Johnson et al., 2001; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson et al., 2002).

Geographers are among the first who should pay attention to the study of neighbourhood effects. However, as the dissertation of De Vos (1997) shows, it was only some three decades ago when geographical neighbourhood effect studies first emerged in Europe. Most of these studies addressed voting behaviour and only some dealt with other issues. Kevin Cox, Ron Johnston and Kelvin Jones were among the most active European researchers to address the neighbourhood effects. Only recently geographers started to pay attention to the impact of the social environment on social mobility in particular. Andersson (2001) and Musterd et al. (2001), for example, carried out large-scale longitudinal empirical research in Sweden and the Netherlands. They used datasets consisting of several millions of individuals and households who could be followed in their social career and in various socio-spatial settings, controlling for other influences on social careers. They found some independent but not very strong neighbourhood effects and had to conclude that additional research should be carried out before stronger answers can be provided. The review by Friedrichs (1998) also suggests that relatively few European sociologists have focused on this issue.

The vast majority of work in both the US and Europe has addressed the question, ‘How much independent effect do neighbourhoods have?’ Multiple methods have been employed to answer this ‘How much?’ question, and a healthy ferment is bubbling about which are most appropriate and where the most fertile advancements might lie, as will be seen below. Relatively few studies have addressed the question, “How does this neighbourhood effect occur?”, one of the first being the methodological analysis by Erbring & Young (1979).

How Much Neighbourhood Effect?

The American literature on size of impact generally has concluded that the neighbourhood environment makes a non-trivial, independent difference for a variety of outcomes, although the impact is not nearly as decisive as parental or individual characteristics, or macro-economic conditions (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1997; Haveman & Wolfe, 1995; Jargowsky, 1997). The measured impact clearly varies according to what sort of outcome is being considered, the age of the person being affected and how neighbourhood is measured. In Europe it appears that neighbourhood effects may be comparatively muted because of significantly different housing supply and social welfare systems that jointly limit the variation of neighbourhood conditions and ameliorate or compensate for these differences through other support programs (Atkinson & Kintrea, 2001; Musterd, 2002). Even this most general consensus is hardly unanimous, however, with some arguing the measured impacts are over-stated and other claiming just the opposite.

Some have argued that most measured neighbourhood effects are biased upward because of selection effects (Evans et al., 1992; Plotnick & Hoffman, 1999; Tienda, 1991). They argue that parents will self-select certain kinds of neighbourhood environments with the intent of bettering themselves and their families. Yet, because typically the variables that measure such motivations are absent from the non-experimental, longitudinal databases analysed, a substantial degree of the apparent statistical association between neighbourhood conditions and various outcomes is, in fact, due to these unmeasured parental characteristics that led to the differential selection of the observed neighbourhood characteristics. Analogous forms of selection biases plague neighbourhood impacts measured from evaluations of US poverty deconcentration programmes, both quasi-experimental designs, as in the Gautreaux and Yonkers programs (e.g. Briggs, 1998; Rosenbaum, 1995), or random-experimental designs, as in the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration (Del Conte & Kling, 2001; Katz et al., 2001; Ludwig et al., 2001).

On the other hand, it has been argued that previous studies create downward biases in the measured neighbourhood effect (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1997). First, they note that implicit in the selection argument above is the notion that a large number of parents believe that neighbourhood is important and act accordingly, thus belying the conclusion of no impact. Second, ‘neighbourhood’ is typically measured in US studies at the census tract, a relatively homogeneous area of 4000 inhabitants, on average. Such tracts might be too large in scale to measure accurately the variables of ‘local neighbourhood’ that actually are affecting residents. Third, readily available demographic and socio-economic data typically employed as indicators may serve as poor proxies for the essence of ‘neighbourhood’ that may crucially affect outcomes, and may evince limited variation in the databases conventionally analysed (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1997). Finally, as argued by Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn (2000) and Sampson et al. (2002), past studies have typically focused on the direct effects of neighbourhood only, not how neighbourhood might also influence outcomes through intervening variables that conventionally are treated as controls. Galster in this issue, for example, suggests that neighbourhood may influence outcomes through related choices of tenure and mobility, and through longer-run changes in household income and wealth.

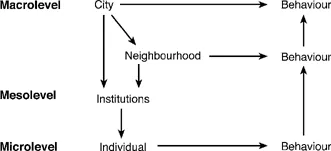

Figure 1. A multi-level model of neighbourhood effects.

The difficulties to specify neighbourhood effects on individuals arise from the complex structure in which the individual is embedded. This structure can be formalised in a multi-level model, shown in Figure 1. Neighbourho...