![]()

Tourism Crises and Marketing Recovery Strategies

Noel Scott

Eric Laws

Bruce Prideaux

SUMMARY. The recent frequency and intensity of crises and disasters affecting the tourism industry has resulted in a growing body of research into their causes, effects and management, as the bibliographies of the ensuing papers catalogue. To date, most papers and collections of research have taken a broad approach, describing the origins of a particular event which triggered a tourism crises, followed by an examination of the differential effects of the crisis on local residents, staff, tourists and tourism organizations or the environment and infrastructure. They have also discussed rescue efforts and the complexity of management tasks in the immediate aftermath of an event, often pointing to the need for preplanning to mitigate the consequences of any future disaster. Other researchers have contributed directly to the academic debate about how to theorise tourism crisis management, often by drawing on the wider crisis management literature.

The present collection of research differs in that it focuses on one phase of the tasks which managers face after the immediate consequences of a crisis have been dealt with. This phase addresses the question of how to rebuild the market for a tourism service or a destination which has experienced a significant catastrophe, and how to learn from the experience in planning for future crisis response strategies. It is suggested in this paper that the challenges are actually more varied and complex than is implied by the suggestion, found in much of the literature, that the task is about ‘restoring normality’. The chaos and complexity experienced in the aftermath of a crisis raise general issues of how organizations learn and adapt to change.

INTRODUCTION

What does it actually mean for a tourism organisation to suffer a crisis and to recover from it? In the case of natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes or tsunamis, the devastation to life and property is all too evident, both to those in the locality and to global audiences who may be described as remote witnesses through the medium of TV, press and internet coverage. Similarly, the suffering and ruin caused by acts of terrorism as well as disasters involving transport, communications and other infrastructure is immediately visible to the global community through the media. The media also rapidly draws attention to the outbreak of a war or insurgency, and on epidemics, thereby turning tourists' travel intentions to alternative destinations. In all these cases the need for rescue, clear up operations and rebuilding is selfevident. It is also widely understood that a further set of management responses are required at a later stage to inform the public and industry partners that tourism services have resumed and that recovery is taking place.

In developing this volume, we have focused on the specific skills and understandings that can assist in post crisis tourism recovery. As the papers in this collection demonstrate, there is more to recovery than the restoration of normal services. Although each crisis has its own distinct causes, impacts and pattern of recovery, it is evident from the papers which follow and from the wider tourism crisis literature that certain tourism organisations are more resilient than others in terms of the speed of recovery and/or their ability to adapt to change in the post crisis period. An organizations' vulnerability to crises and the effectiveness of their recovery efforts vary in ways, and for reasons which are not yet fully understood.

Earlier studies of crises (including previous work by the present editors; Laws, Prideaux and Chon, 2007; Laws and Prideaux, 2005; Prideaux, Laws and Faulkner 2003; Campiranon and Scott, 2007) have focussed on management of the crisis itself and have highlighted how a crisis precipitates a complex and changing situation where the pre-existing rules of action for the organisation are suspended and other tasks take priority. These other tasks lack the normal clarity of organisational procedures, and at first glance many appear to be difficult to prioritise on the basis of past experience. There may be no consensus about what to do, how to do it and who should be undertaking the work. In these situations, leadership becomes a critical issue, both within an organisation and in terms of coordinating and directing the multitude of stake-holders participating in recovery. In summary then, crises are chaotic, dynamic and dangerous and are events where leadership becomes a key factor in prioritization, redirection and creation of new patterns of post event activity.

In this paper the editors of this volume argue that tourism crisis recovery may mean a change to the pre-existing ways of operating. The standard means of measuring recovery by the success of an organisation in restoring business flows to an earlier trend line may not be adequate because this benchmark it does not take into account the adaptation that may take place during the crisis and ensuing recovery period processes. The consequences for an organisation of a crisis (beyond its immediate impacts in terms of suffering, damage, and loss of business) are often more fundamental and may necessitate changes to the way the organisation operates, forces it to create new networks, and even stimulate the development of new business opportunities or social objectives.

The objectives of this paper are to: present a summary of theoretical understanding of tourism crisis management from the perspective of crisis recovery with a particular emphasis on the systems approach and the role of networks; to introduce the other papers in this collection; and to contribute an adjustment to Faulkner's (2001) model of disaster management to incorporate that role of marketing in post crisis recovery. This aspect of the paper is summarised in Figure 4.

The objectives of this paper are to: present a summary of theoretical understanding of tourism crisis management from the perspective of crisis recovery with a particular emphasis on the systems approach and the role of networks; to introduce the other papers in this collection; and to contribute an adjustment to Faulkner's (2001) model of disaster management to incorporate that role of marketing in post crisis recovery. This aspect of the paper is summarised in Figure 4.

TOURISM CRISIS RECOVERY — AN OVERVIEW

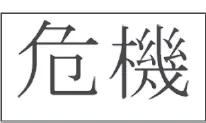

From the practical perspective of managers, the general challenge of the recovery phase is to restore operations to normal, but increasingly there is evidence of more radical, strategic thinking in reshaping the offer as social and tourism infrastructure, equipment and even staff may have to be replaced, new patterns of operation developed and new markets sought. It is in this context that viewing tourism as a system has a number of advantages. It is interesting that the Chinese word for crisis (shown in Figure 1) is composed of two symbols meaning “danger” and “opportunity”. Some destinations, including a number of Thai resorts devastated by the 2004 Boxing Day Tsunami, have

FIGURE 1. The Chinese Word for Crisis Is Composed of Characters Meaning Opportunity and Disaster

used the event as an opportunity to restructure by identifying new market segments and in some cases discouraging some market sectors they feel are less desirable. This usually equates to ‘moving up market’. A related recoverys trategy focuses on rebuilding high margin sectors such as MICE (Campiranon and Arcodia, below).

The focus of much of the existing research has been on the events leading up the crisis which then results in a perturbation of the normal state, followed by the steps required to restore the ‘normal’ situation. In their review of different perspectives on the study of crises and their development of propositions for further study, Pearson and Clair (1998:6) discuss the outcome of a crisis as a system being restored to its normal state. This approach views the crisis as distinct from the remainder of the environment in which the organization functions, with the consequences of the crisis affecting internal technical and social elements of the tourism system operating at the time of the onset of the disaster or crisis event. Restoration in this view is achieved through a series of steps or stages. An alternative view is to consider crisis events from a systems perspective where a change such as a crisis event causes changes to other parts of the system. In many cases these changes have system wide implications that prevent a return to the precrisis specifications of the system.

The previous discussion has conceptualized the study of crises and disasters by using a view of tourism systems in which there exist networks of organizations. Three implications of this should be considered. First a systems view questions the boundaries that should beused to study crisis and disasters. Second, the idea of complexity or chaos theory can add new insights to recovery. Third, a social network view provides a different perspective focusing on the interactions between organizations. Together, the implications point to the need to review existing models and incorporate new perspectives from the lessons learnt during recent disasters and crises.

The Role of Boundaries

A systems perspective is useful as it highlights another range of effects or impacts of crises that have not been sufficiently recognised within the tourism literature. Scott and Laws (2006) discussed the idea of system resilience, of change in system states and in improvements or degeneration in the overall system of tourism as a result of acrisis. These ideas were also identified and explored in a paper using floods in Katherine, Australia asa case study to examine how a disaster may lead to a positive change in a destination's tourism (Faulkner & Vikulov, 2001).

Within a system the impact of an event such as a crisis is felt to either agreater or lesser scale by all members of the system. The implication of this is that the effects of a crisis may be transferred across system boundaries by organizational relationships. As a simple example, a baggage handlers' strike at one airport may delay passengers, impose costs on airlines in accommodating passengers, moving luggage and rescheduling flights, and result in extra stress for airport staff. However it may also have follow on effects at distant airports and cause a loss of business to hotels in those destinations. Systems theory perspectives can therefore assist to identify the range of stakeholders involved, and lead to a study of factors influencing speed of recovery, the intensity of effects and the factors causing the effect (see Armstrong and Ritchie; Carelsen and Hughes; and Vitic and Ringer, below).

Complexity or Chaos Theory

Complexity or chaos theory provides an insightful paradigm for the investigation of rapidly changing complex situations where multiple influences impact on non-equilibrium systems. In these conditions of uncertainty, there is a need to incorporate contingencies for the unexpected into policy framework that may result in adaptation of the system itself. Chaos theory demonstrates that there are elements of system behaviour that are intrinsically unstable and not amenable to formal forecasting. If this is the case, a new approach to forecasting is required. Possible ways forward may include political audits and risk analysis to develop a sense of the possible patterns of events that may emerge. In this sense future tourism activity may be forecast using a series of scenarios. The latter may involve the use of a scenario building approach incorporating elements of van der Heijden's (1997) strategic conversion model, elementsof the learning organisation approach based on a structured participatory dialogue (Senge, 1990) or elements of risk management described by Haimes et al. (2002). Which ever direction is taken, there are a number of factors that must be identified and factored into considerations of the possible course of events in the future. A typical large scale disruption precipitates complex movements away from the previous relation ships which often trend towards stability and partial equilibrium. Keown-McMullan (1997: 9) noted that organisations will undergo significant change even when they are successful in managing a crisis situation. It is apparent that traditional Newtonian (linear) thinking with its presumption of stability is not able to adequately explain the impact of crises where the previous business trajectory is altered and a new state emerges.

Richardson's (1994) analysis of crisis management in organisations provides another perspective on community adjustment capabilities by drawing on “single” and “double loop” learning approaches (Argyris and Schon, 1978). In the former, the response to disasters involves a linear reorientation ‘more’ or less in keeping with traditional objectives and traditional responses (Richardson, 1994, 5). Alternatively, the double loop learning approach challenges traditional beliefs about what society and management is and what it should do. This approach recognises that management systems can themselves engender the ingredients of chaos and catastrophe, and that managers must also be more aware and proactively concerned about organisations as the creators of crises. Pike (below) presents a cautionary tale of a destination which suffered a crisis through its inability to recognise that changing government policy could adversely affect it. As Blackman and Ritchie (below) point out, lessons can be learned from the experience of a crisis, or from studying other destinations and organisations which have experienced serious disruption. Forexample, the absence of any post crisis recovery planning and action following the 1994 volcanic eruption in Rabaul, Papua New Guinea resulted in a slow decline of a destination that was internationally recognised as a dive location. Today, former...