![]()

Introduction: Independence Day Ceremonials in Historical Perspective1

DAVID CANNADINE

Institute of Historical Research, University of London

Colony by colony, the [British] Empire was dismantled … The procedure became almost standard, like an investiture … Down came the flag, out rang the last bugle…. Out from England had come some scion of royalty; and there was an Independence Day ball, at which the new Prime Minister danced enthusiastically with Her Royal Highness; and there were sundry ceremonies of goodwill and fraternity … Just for a moment they all meant it, and it seemed hardly more than a passing of tradition from one hand to another, or a coming-of-age.2

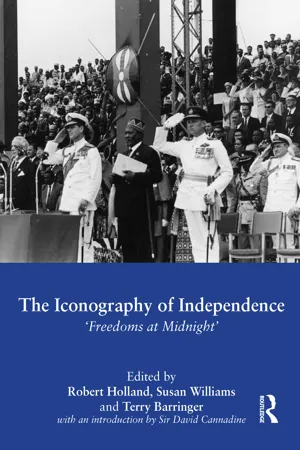

When I was growing up in Birmingham during the 1960s, there were two unforgettable images that repeatedly appeared on the evening news bulletins on our recently-acquired television. They were from distant places, to none of which I had yet travelled, but they intruded themselves so regularly and so insistently into our living room that they were formative influences on my youth, as I suspect they were for many members of the immediate post-war generation to which I belong. From one perspective, these pictures were as different in their frequency as they were dissimilar in the stories they made so vividly visible. Night after night, or so it seemed, there were horrifying images of B52 bombers dropping napalm on the cities and rice fields and peoples of Vietnam, in a violent, brutal and ultimately vain projection of American military might and global reach to a far-off land of which most of us knew nothing. Less often, but at least once, and sometimes twice or three or even four times a year, there was a very different item on the television news, reporting that the Union Jack had been pulled down at midnight, in a former British colony, in the presence of a member of the royal family, and in a newly built stadium located in the capital city.3 Thus was power transferred from the old empire to a new nation, and from a pro-consular elite to a popularly elected government, in the orderly and dignified manner described by James Morris, and on what would thereafter become known in the newly begotten country, following the American precedent of the fourth of July, as its Independence Day.4

At the time, these different and discrepant images seemed to be depicting two distinct and disparate worlds and, as such, they were particularly reassuring to those in Britain who believed (as many did then, and some still do now) that we were much better at dealing with non-western parts of the globe than were the Americans. The British understood empire, so this argument ran, which meant we were able to end our own dominion over palm and pine relatively amicably and successfully, with the result that many former colonies, on achieving their independence, immediately joined the Commonwealth; the Americans, by contrast, never comprehended or appreciated empire, and so it was scarcely surprising that they botched their neo-imperialistic intervention in the former colonies of French Indo-China.5 Yet for all these contrasts and dissimilarities, the traumas of Vietnam (and of neighbouring Laos and Cambodia), and the ceremonial obsequies of the British Empire, were parallel and simultaneous manifestations of the same contemporary trend: for they were both part of that process whereby relations between ‘the west’ and those large areas of the rest of the world which had previously been European colonies, were being re-negotiated and re-configured.6 And the decade in which those relations were most significantly altered and fundamentally adjusted was the 1960s: at the beginning of it, as Harold Macmillan made plain in his ‘winds of change’ speech, delivered to the South African parliament in Cape Town in February 1960, the British Empire had become unsustainable; by the end of it, the American intrusion into Indo-China was doomed to failure.7

Such were the mood and the mores of that decade, so it was scarcely surprising that, when Bernard Levin produced his coruscating contemporary history of Britain during the 1960s, which was published in London as The Pendulum Years, it was repackaged in the United States, more resonantly and more imaginatively, as Run Down the Flagpole.8 It was a good alternative title, for while it took the British half a century to wind up their global imperium, from the independence (and partition) of India and Pakistan in 1947 to the Hong Kong handover precisely 50 years later, it was during the 1960s that that process of imperial withdrawal was at its most intense, and there were more independence celebrations across that decade than during the 1950s (when the momentum of African decolonization was only beginning to gather), or the 1970s (by which time most of the British Empire was truly one with Nineveh and Tyre). Indeed, so frequent were these imperial departures and goodbyes between the years 1960 to 1970 that a retired British army officer, named Colonel Eric Hefford, embarked on a new (but essentially time-limited) career as a sort of late-imperial, trans-oceanic, globe-trotting Earl Marshal, organizing the events that declared and proclaimed ‘freedom at midnight’: in one guise he was the undertaker of the British Empire, orchestrating valedictory colonial observances, in the other he was the impresario of freedom, planning the independence day celebrations by which new nations came to birth.9

Taking a longer view across the half century from 1947 to 1997, there were more than 50 such occasions in as many years, and they form an extraordinary and unique sequence of hybrid spectaculars—collectively for the British Empire whose end they signified and symbolized, and individually for the post-imperial, successor states whose beginning they marked and memorialized. To those who regard such state-sponsored flummery as nothing more (or better) than insubstantial pageants and tinsel ephemera, such happenings are of no scholarly interest or historical significance; but since the British Empire had (among other things) existed and endured as a pageant, it was at least consistent with that element of caparisoned theatricality that it ended and expired in a succession of valedictory rituals, which were not so much, as Colonel Hefford claimed, “plucked from the book of ancient British traditions”, but were deliberately made up and self-consciously invented.10 It is more than ten years after the Hong Kong handover, it is nearly 40 years since the peak decade of independence ceremonials by which I was so struck when I was growing up, and it is over 60 years since the initial celebrations took place in New Delhi and (less enthusiastically) in Karachi; and this means there is now sufficient distance on these episodes and events to see and study them in a historical perspective which, as so often in imperial and post-imperial matters, is simultaneously global and general, yet also place-bound and particular.

I

The independence ceremonials that took place in Britain's former colonies between 1947 and 1997 form, in all conscience, a large enough topic, encompassing substantial parts of the globe across half a century; but like many aspects of the history of empire and of decolonization, they also need to be de-parochialized, and set in a longer historical time-frame and a broader geographical perspective.11 Before 1776, the very notion of a former colony becoming ‘independent’ of its conquering coloniser was scarcely conceivable, and in the early modern period (and in certain instances thereafter) the great European powers regarded their overseas territories as possessions, which might be won or lost or (occasionally) exchanged, but which never gained or were granted something called ‘freedom’. The Mediterranean island of Menorca, for instance, was traded back and forth across the 18th century between Britain, Spain and France, and was eventually ceded by Britain to Spain in 1802.12 In the same way, the Ionian Islands were given to Greece in 1864, Heligoland was returned to Germany in 1890, and Wei Hai Wei went back to China in 1930. Indeed, it is in this venerable category of territorial transfer and exchange between great powers, rather than that of colonial liberation from a European empire, that the handover of Hong Kong to the Chinese government ought to be set. For no one seriously believed that Britain's last great colony was becoming a free and independent nation state in 1997.13

There were also three instances of colonial separation from the British Empire, well before 1947, and none of them were marked by the sort of celebrations and fireworks and transient expressions of mutual admiration that subsequently became so familiar. The first ‘British experience of decolonization’ was the rejection of imperial authority by the 13 colonies from the mid 1770s: royal statues and coats of arms were torn down by rebellious Americans; the Declaration of Independence denounced George III as an evil and wicked tyrant; and after the British defeat at Yorktown in 1782, there was nothing for it but for the King's troops to cut and run and scuttle.14 The second was the creation of the Irish Free State in the aftermath of the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. Unlike the 13 former colonies, this new nation did not initially repudiate the British connection, but instead became a dominion within the Empire. Yet once again, there were no independence celebrations: the last British Lord Lieutenant, Viscount Fitzalan, departed from Dublin Castle in 1922 in a private car; the low-key successor post of governor general was abolished in 1937; and Eire eventually became a fully independent republic outside the British Commonwealth on Easter Monday 1949,...