- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Growing Child And Its Problems

About this book

First Published in 1999. This is Volume of thirty-two in the Developmental Psychology series. Written in 1937, the object of this volume of essays is to provide insight into problems presented by the mental growth of children from five years of age to the close of adolescence. It is also hoped that guidance will be obtained in steering children through the difficulties encountered in these years when school life begins and presents to the child special stresses.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Health Care DeliveryI. THE CHILD’S NEEDS AND HIS PLAY

By GWEN E. CHESTERS, B.A., INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL PSYCHOLOGY

I. THE CHILD’S NEEDS AND HIS PLAY

By GWEN E. CHESTERS, B.A., INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL PSYCHOLOGY

CHILDREN play the world over. We have all played and we still play; perhaps it is this very universality and constancy of play which makes it possible for us to overlook much of its significance. Deprived of play we should be hardly better off than the proverbial fish out of water. We may not play by active movement; we may not mean to play at all; but we do play, if only in thought. Play should not be regarded as waste of time, or even as a means of merely passing time. It is more than purposeless activity. The effect of “too much” play has often been feared. It has been said that “if boys play when they are boys, they will play when they are men”, and, indeed, it is to be hoped they will, though not in the way implied in the saying. Through fear of its effects, play is sometimes curtailed, in a genuine if mistaken effort to encourage hard workers and a serious outlook on life. The results of such curtailment are often exactly the opposite to those intended.

It has long been recognized that:

All work and no play

Make Jack a dull boy,

yet, though we condone his weakness, we have a feeling that Jack is none the less weak to need to play. Jack’s work, however, rests to a great extent on his play, and his play, as spontaneous, non-directed activity, has a function peculiar to it. Play is the means by which we make good needs not satisfied in any other way. We are to a great extent controlled by our needs, and it is in playing that we relieve many of the stresses we experience, almost without realizing that we are doing so. Through play we preserve our balance emotionally, free ourselves of the domination of primitive tendencies and so become capable of more developed interests and happy social relationships.

Though play is part and parcel of our life, it is by no means certain that at the present time all children have the sort of play they need. Under the usual conditions of modern life it is easy for the child’s play to be inadequate for his needs. There is nothing artificial about good play, and natural surroundings always provide the means for it, however undeveloped these may be. If we were more primitive, we could perhaps afford to give less thought to provision for play, but in becoming to some extent civilized we have unwittingly allowed ourselves to be deprived of elemental play material, and, not realizing its significance, we have provided faulty substitutes for it. Many children have little contact with natural things, not enough space in which to play, and not enough natural material to play with. Even children who may have such opportunities can often make only restricted use of them. They have to be too clean and to play in too tidy a way. They may have elaborate toys, but these are not always the boon they seem, and are poor compensations for the lack of plentiful natural material. It is not possible for us all to live where there is free space with its wealth of play material, but there is a lot we can do to minimize the disadvantage. There is much material within reach of all of us which can meet the child’s needs and support his spontaneous development.

If we are to understand the function of his play and how best to provide for it at any stage, we must review briefly the child’s general development and its relationship to his play. Play is related to the whole life of the child, it is not an isolated piece of behaviour. It shows some sequence as the child develops, but appropriate play cannot be regarded as rigidly determined by age. The sort of play suited to any particular child will depend upon his choice, which in its turn will depend largely on his previous experience and his general state, rather than on his chronological age. Hence successful play in adolescence will be determined by the satisfactoriness of earlier play, and it is therefore of great importance that the child’s play life should be sound from the start. Play may be as much related to the past as to the present. Knowledge of his earlier development and requirements, and so perhaps of his deficiencies, will help us in making provision for him at any later stage. His play affects and is affected by his physical, intellectual, social and emotional development, and so as better to understand their general interdependence we will briefly discuss these four aspects of his life in relation to his play.

We will consider first his physical development. By the time he is five he has normally acquired good control of his body. He has progressed from the lying-down stage, through those of sitting-up, crawling, climbing and walking, and has at the same time gained skill in making many fine and specialized movements. He is very active, and the growing possibility of wider exploration and more skilled movement is a source of great satisfaction to him. Throughout the middle years of his childhood, just as earlier, much of his play tends towards, and in its turn is dependent upon, the development of his musculature, the perfecting of existing skills, and the acquiring of fresh ones. As he reaches adolescence his physical activity generally follows more specialized lines, and more developed interest is added to his pleasure in general physical exercise.

Intellectually the child shows a similar interdependence of play and development. At five years he is aware of his separateness from other people and things. His world has gradually become organized. He knows himself and other people and objects as separate things, though he tends to give them meanings of his own. Many “real” things have for a long time some imaginary significance, but ultimately he separates the real from the imaginary. If progress has been smooth his interest has moved gradually from himself and his immediate concerns to other people and the objects of their interest, and then to similar and different things. All this has occurred largely through his play, where he has had social opportunities of exploration and experimentation. His ingenuity and initiative have been roused and developed, and his interest, through finding a progressive outlet, is available for more cultural pursuits. The development of his speech has increased his possibility of interplay with other minds, and made more developed forms of play possible to him. All through his childhood he will learn from play, and continued exploration and experimenting will at the same time satisfy and maintain his curiosity. As his more primitive interests are satisfied, and his feelings given adequate outlet, he becomes free to follow his genuine interests without over-strong emotional bias. As he grows up, the field of his knowledge widens, and he becomes increasingly able to solve the problems presented by the things round him. Supported by his growing intellectual satisfaction, he becomes more and more capable of sustained effort in the pursuit of his enquiries, and progresses towards a stable cultural level. Such development is spontaneous. We can help him by making provision for his curiosity, and we must be careful not to damp down his enthusiasm by limiting him to restricted and over-specialized lines of enquiry at an early age. At a time when orthodox learning tends to follow a rather artificially selected range of subjects, it is increasingly important ,that the child should find opportunity of making good the deficiency through ample free play in a sympathetic environment.

His social development up to five years makes many demands upon him. Gradually he progresses from absorption in himself, his mother and those most nearly surrounding him, to the gradual acceptance of more and more substitutes for his early relationships and the sharing of his interests with them. His play reflects his social progress. A very young child plays to a considerable extent within himself. He responds to the play of others, but lacks the capacity for making very active play advances to them. As he develops, his play makes demands on the attention of other people and he arranges his play in accordance with his needs. Then he begins to allow for other people’s wishes in playing, till he can play in a more co-operative way. His interest is stimulated by being shared, while its centre moves from himself and his immediate concerns. This gradual extension of his interests and his social contacts will continue all through his childhood, and the fostering of it is one of the most important functions of his play. It is in play that he can find adequate companions in his contemporaries, form sound co-operative relationships with them, and pursue shared interests without undue dependence on other people. He is safeguarded against dislocations of feeling, and ultimately achieves good give-and-take social behaviour not only in his play but in all his activities.

The child’s emotional life is bound up with his social, intellectual and physical life — they are of course all interrelated — and in reviewing them we have already in part considered his emotional life. There can be no rigid definition of a child’s emotional life at the age of five, but some things are true of him then as at any age. A child is potentially as happy and good as he is miserable and bad, and it is more normal for him to grow up happy and good than otherwise. A baby shows responsive, friendly feeling, confidence in those around him, great initiative, cheerful persistence when confronted with some obstacle, and much pleasure in activity and achievement. He also shows anger, anxiety, fear and grief in unduly difficult situations, and in these he appeals for help and comfort. A child has little control of his real situation, and little general understanding of it, and sometimes everyday circumstances or our own lack of insight increase the difficulty. But normally his happiness and confidence are preserved, and his unpleasant feelings reduced, as he has sympathetic handling and opportunity for the development of his own understanding and tolerance of the situation. Through play his pleasure and trust in life are maintained, and his capacity for meeting his experiences with sane and confident optimism develops. There are, however, many problems liable to disturb the child as he grows up, and here again his play is of the greatest importance. Children experience nursing, feeding, and cleanliness training, and these experiences are frequently associated with disturbed feeling, which persists when the actual circumstance with which it was connected has ceased to exist. There are also problems of thwarted activity, of lessening dependence on others, of family and social relationships, and of sexual development, each of them invested with feeling needing relief. The child’s general balance is easily disturbed and his mental health depends upon its progressive restoration. In play he can express and find some solution of his problems. His phantasies are played out and his feelings relieved. His most valuable and variable means of maintaining his confidence and happiness, of meeting the strains and stresses he experiences, and of helping forward his own development is play, and this holds good for play at any age.

We have seen that play has a varied function for the child, and it may make the basis of our provision for him clearer if we summarize briefly our conclusions. In play he can exercise and gain control of his body; his interest is stimulated, satisfied and widened; his social feeling built up; his happiness maintained, and his feelings balanced. Without adequate play his needs remain unmet, and faulty and retarded development results. We can now consider how best we may provide for him, and we must bear in mind that this means both social and material provision. It will be simpler to consider these two aspects separately, though in practice there is no such division.

The child’s social problem is the modification without dislocation of his early relationship to his mother, and he can be greatly helped in its solution through his play. He cannot be satisfactorily forced away from his mother, but she herself can help him to accept other interests by presenting him with them. His friendliness for her can be sustained, while his feeling and interest are spread from her to things she is doing, to other people round her, and to the things they are doing. His dependence on her alone lessens as he finds friendliness in other people and accepts them happily, and it is on a play level that social development can most easily be fostered. Failure to meet his need at an early age will make him over-demanding of attention later, and it is more difficult to satisfy him then than at the right time. An infant is largely dependent on others for his play. He needs play with other minds in a form in which he can take part. That is to say, he depends at this early age on other people’s active play with him, as later he will need and enjoy play with them on a more intellectual level, either directly in talk, or more indirectly in reading, music and art. Most of us play intuitively or unwittingly with a small baby, by giving him freedom of movement, and time to enjoy his bath; by talking to him as we bath, dress and feed him, and generally attend to his needs; by showing him brightly coloured and moving things and putting him where he can see them, and in many other ways. It must not be supposed that such play on our part is trivial or unnecessary. It is in this way that the infant’s contact with his mother is developed yet preserved, as he is given means of extending his interest. When he can sit up, he will enjoy being where household and outdoor work are being done and he should be talked to and not ignored as if he had “no mind”. When he can crawl and walk he will take a more active part in joining in the work, and this for him is play. A fifteen-months-old baby will make his “dinner” in a saucepan, “polish floors”, and “dig”. A small child needs early opportunity of finding pleasure in varied companionship, and it is good for him to play where there are other children, at first rather older than himself and more socially developed. He will soon be found to be imitating their play, and his contact with others is thus further strengthened and the sphere of his interest widened. The age at which a child plays happily with other children depends very much on his experience of them, but his social development will be smoother if he has an opportunity of being with them from a quite early age. He needs the companionship of his contemporaries to help him relinquish his mother without resentment, particularly if he is followed by other babies in his family. His emotional stresses are also greatly eased by his having other children to join in his dramatic and make-believe play, and their presence saves him from becoming too much engrossed in his own phantasies. By the time he is five he should play happily with other children. If he is found towards this age to be still very demanding of adult attention, lacking in interest, unwilling to play with other children or unusually hostile to them, he is needing play in some setting other than his usual. Many nursery schools are run on play lines, and here the child has the needed support of a friendly adult as he makes and strengthens his contacts with other children. From the age of five onwards he increasingly enjoys the companionship of other children. Playing in “gangs” is a normal and spontaneous form of play from the age of six or seven onwards, and is one of the ways in which the child establishes his feeling of oneness with other children, and finds support for his growing social feeling, and for the development of socially directed independence. With other children the child can play and invent innumerable group games, achieving at the same time a sound co-operative relationship with his fellows and a truer sense of proportion. The development of a ready sense of humour depends also to a great extent on the child’s opportunities for play with other children. Throughout his childhood and his youth he needs other boys and girls with whom to play and with whom to share interests, while he must feel that the grown-ups in his immediate circle are genuine, disinterested companions who can appreciate and share his activities without forcing these along their own lines, and yet will let him share their interests as he is able. In playing with him they must let him take the initiative, and be content to follow his lead.

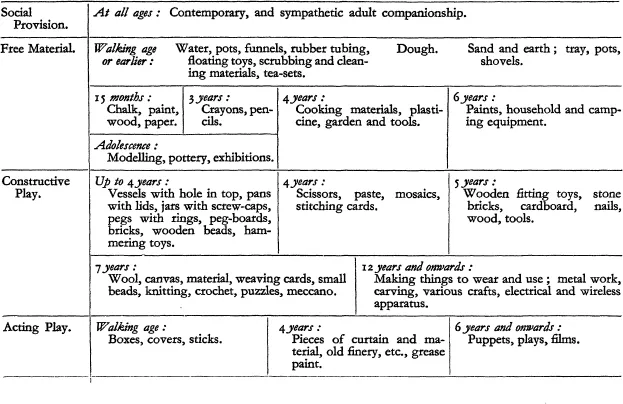

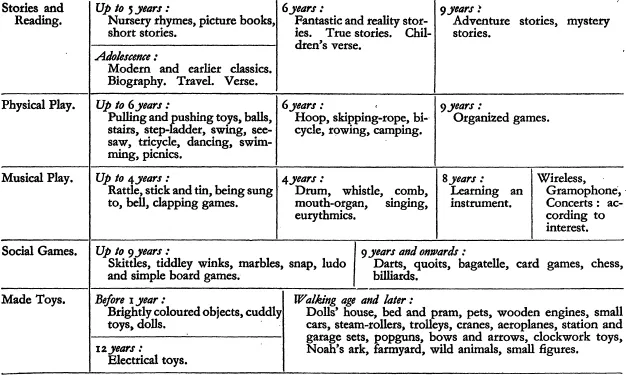

PLAY CHART

The ages given are those at which material * should he introduced, hut are only approximate.

* The material suggested here for earlier ages should be available to the older child until he abandons it of his own accord.

In addition to playing with the child, adults have a role seemingly more apart from, yet having a direct bearing upon his play, and if they fail to fulfil this role the child’s play and general progress will inevitably be hampered. While they meet his social and emotional needs, they must give him the necessary intellectual support. The child has many questions which his contemporaries are no better able to answer than he is, and if he lacks necessary explanations his phantasy solutions will be unduly primitive and prolonged, and his play will be dominated by phantasy to the impeding of his exploration of reality. , The child’s body is an object of great interest to him, and at the same time a source of constant phantasy. He is concerned both with its structure, its “goodness” and its safety. Most children at some time ask questions about their bodies, but, whether they ask questions or not, they should be talked to about the body as a matter of intellectual interest. His strong bones and supple joints with their general arrangement, the little “pipes” for blood and the holding of blood within tissue, how he breathes, what happens to food after it has gone into his mouth, and the fact that he “grows mended” after he has cut or hurt himself, are all matters from the understanding of which the child gains support for his developing curiosity and feeling of general confidence. Without understanding, he remains preoccupied. He is equally if not more interested in where he came from and how he was made, and if left unanswered these problems may arrest the all-round development of his play. There are also many questions about the things that he hears of and sees, and as his interest extends from his own concerns it must be satisfactorily met. The fuller meeting of it is for the most part inevitably left, under our present system, to his so-called education, but where this tends to be too specialized to serve the child’s more general enquiries, a sympathetic hearing at home and the making available of the needed means of satisfaction, must make good the deficiency. The progress of his play to a level where difference in intellectual and emotional demand is one of quality not quantity, while it depends partly on the meeting of his emotional and social needs, is to some extent determined by the provision made for his intellectual development; and it rests largely with adults to help this intellectual balancing of his play.

The discussion of the provision of play material will, of necessity, seem more detailed, but the importance of the social aspect of play must not be lost sight of. Any material can serve as a basis of social play, while some, as we shall see later, is more particularly suited to it. As was suggested earlier, appropriate play material is not altogether age-determined. An attempt will consequently be made here to present it in sequence rather than to classify it according to age. The accompanying chart of play provision gives a rough age classification. Some children seem to play very little, or to use material in an irrelevant way, and this may be because their supply of more primitive material has been inadequate. Sequence of material will therefore be of help in suggesting what earlier material might meet their need. Some children are found to be troublesome and “never out of mischief”, and they may be suffering or have suffered from a general lack of adequate material, and for such children earlier forms of provision are more necessary than those supposedly related to their age.

There are some kinds of play which can stand us in good stead throughout our lives, and though the forms of such play are of great variety, they will be found to be related to primitive kinds of activity. It will be these more permanent and consequently essential kinds of play with their modifications which will be first considered. They will, in the main, be found to be connected with play with free materials, with acting play, with physical play, with banging and “noise” play and with constructive play.

Play with crude materials will first be discussed together with the sequence of play to which it gives rise. These materials provide the child with the means of bridging the gap between his phantasy and reality play, for with such materials he can play according to the needs of his feelings, and at the same time explore and gain understanding of the possibilities of the material, with as much satisfaction in such exploration as in the expression of his phantasies. They help him in the levelling up of his mental development. His feelings are eased and modified, his activity stimulated, and his thought brought into play. A child needs to be able to express his destructive tendencies, and to relieve the underlying anger and anxiety, and crude materials meet this need as no other material can. The child can “ill treat” the material, or destroy what has been made, without doing real damage, and with the possibility of making again. Crude materials allow also for his need to make a mess and to clean up, with the relief of the related feelings and phantasies. He can use them, too, for genuine constructive play. The unifying effect of play with this sort of material helps forward his general mental organization. As his more primitive interests are satisfied and his think...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter I. THE CHILD’s NEEDS AND HIS PLAY

- Chapter II. EDUCATIONAL GUIDANCE

- Chapter III. THE ADOLESCENT GIRL

- Chapter IV. PERSONALITY DEVIATIONS IN CHILDREN

- Chapter V. HABITS" href="ch5.html

- Chapter VI. NEUROSIS IN SCHOOL-CHILDREN

- Chapter VII. PROBLEMS OF THE GROWING CHILD

- End NOTES

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Growing Child And Its Problems by Emanuel Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.