- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Nature of Intelligence

About this book

First published in 1999. The author writing in 1923, starts with the assumption that conduct originates in the actor himself, and tries to discover what intelligent conduct may mean if we follow this assumption to its limits. He then sets about to harmonize three schools of thought about human nature which have the appearance of being irreconcilably disparate. Stated in a nutshell, his message is that "psychology starts with the unrest of the inner self, and it completes its discovery in the contentment of the inner self".

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Nature of Intelligence by L L Thurstone,L.L Thurstone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

THE STIMULUS-RESPONSE FALLACY IN PSYCHOLOGY1

1 The old and the new psychology

2 Stimulus-response

3 The dynamic self

4 The psychological act

5 Psychology as a science

6 Stimulus-response in the animal mind

7 Summary

I. THE OLD AND THE NEW PSYCHOLOGY

There has lately come into prominence before the reading public what is known as the New Psychology. This so-called new psychology is concerned with a wide variety of mental phenomena which have a strong interest appeal to every intelligent person. It purports to explain to us our dreams, our slips of the tongue, our forgetting, our prejudices, how personality is made, and many other mysteries in which we are all interested. It deals with considerable confidence in the problems of capital and labour, economic motives, peace and war. No wonder that it is attracting attention.

As we read the literature of the new psychology we stop to recall our psychological reading of ten or fifteen years ago, and we find that the two kinds of psychology do not even use the same language. The terminology is entirely different. In the psychology which has become established in universities, the categories include sensation and perception, imagination, reasoning, the sense organs, memory, the affective states, and so on. These terms have a familiar sound to anyone who has ever taken a course in psychology. In the new psychology we read about complexes, rationalization, projection, compensation, identification, symbolism, repression, the wish, and many other categories that do not even occur in the indexes of standard textbooks of the subject. What is the fundamental reason for the disparity between the established type of psychological discourse and the so-called new psychology ?

There are several factors that contribute toward this disparity in psychological language, and it is well to keep them in mind in order to understand the present tendencies in the interpretation of mental phenomena. First we must recall the different origins of the old and of the new psychology. The old psychology was written partly by philosophers and later by psychologists who devoted themselves to the scientific study of mind. The new psychology and particularly psychoanalysis has been developed by those physicians who have devoted themselves primarily to the treatment of mental disorder. Here we have two different types of training for the men who represent the two different types of psychology. In general, a fair-minded student would probably admit that the new psychology deals with subjects that are more generally interesting than those which he may recall from his textbooks. On the other hand, one must admit also that the psychology of the standard textbooks is written with greater regard for scientific consistency. The new psychology has very little regard for scientific method, and it does not rest on careful experimental work to ascertain the facts. Nevertheless, the new psychology has a strong appeal to our interests, and in large part its propositions seem to be very plausible. It is only natural that the physicians who devote themselves primarily to the treatment of disordered minds should pay attention mostly to the methods that work, while the psychologists, as scientists, should pay attention mostly to the scientific experimental methods for establishing facts.

Another factor that partly explains the difference between the new psychology and the old is to be found in the character of the mental phenomena that are the basis of the two schools. The psychiatrist deals with minds that are abnormal, minds that have broken under stress of some kind. The psychologist deals with normal minds, minds that are sufficiently calm, quiet, and contented, to submit in the psychological laboratory to experimentation. Obviously the materials on which the two schools of psychology are built up differ at the very source of the observations.

The normal person who has sufficient leisure to serve as a subject of experimentation in the psychological laboratory is not likely to have any major mental disturbance and distress. If, on the occasion of a peaceful psychological experiment, he is mentally disturbed by any serious issue in his fundamental life interests—financial, sexual, social, professional, physical—he reports that he is indisposed, and he does not serve as a subject. It is therefore relatively seldom that the psychological laboratory gets for observation persons who are in a mental condition of major significance. The psychiatrist, on the other hand, continually observes persons whose mental states are dominated, or broken, by issues that are close to the fundamental mainsprings of life.

It is only reasonable, therefore, that we should find a fundamental difference between the new and the old psychology as regards the significance of the mental phenomena that they represent. The established forms of psychological discussion relate mostly to the momentary mental states and related phenomena, such as the sense qualities, colour mixture, the taste buds, the visual illusions, the reflexes, peripheral vision, reaction time, the learning and forgetting of nonsense syllables, the fields of attention, visual and auditory imagery, the momentary nature of emotion, the difference between instinctive and habitual actions. All of these, and in fact most of the discussions in the standard textbooks of psychology, refer to the momentary mental states, situations in which a laboratory experiment may be prepared and in which the subject reports what he at that moment sees, or hears, or feels. There is no criticism to be made against all this scientific experimentation except that it seldom relates to the permanent life interests of the persons who lend their minds to the psychological experiments.

In the new psychology we deal, on the other hand, with a whole series of explanatory categories that have their origin in the psychopathic hospitals, where every person observed is giving vent to a disturbance in the fundamental and permanent mainsprings of his life. This contrast between the new psychology and the old is summarized by noting that the established forms of psychological writing deal mostly with the momentary mental states, while the new psychology deals mostly with the expression of basic and permanent human wants.

There are, of course, many secondary branches of these two large schools of psychology, and there is an ever-increasing number of men who can straddle both schools; but it is clear that their interest in the permanent life motives comes from their clinical experience, while their interest in rigorous scientific experimentation comes from the peaceful psychological laboratory in the college.

The two schools represent two widely differing points of view in the study of the mind, and it is our purpose in these chapters to assist in bridging the gap so as ultimately to combine the worthy features of both schools of thought into a consistent interpretation of the human mind.

One of the basic differences between the old and the new psychology is in the treatment of the stimulus or environment. Writers of the academic schools of psychology treat the stimulus as the datum for psychological inquiry. They put their subject into the laboratory, and confront him with stimuli of various kinds, colours, noises, pains, words, and with the stimulus as a starting-point they note what happens. The behaviour of the person is interpreted largely as a mathematical function of the stimulus or environment. The person's own inclinations are of course recognized as constituting a factor in the situation, but only as a modifying factor. The stimulus is treated as the datum or starting-point, while the resulting behaviour or conduct is treated as the end-point for the psychological inquiry. The medical writers on psychology state or imply a very different interpretation of the stimulus. Here, the starting-point of conduct is the individual person himself. He wants certain things, he has cravings, desires, wishes, aspirations, ambitions, impulses. He expresses these impulses in terms of the environment. The stimulus is treated by the new psychology as only a means to an end, a means utilized by the person in getting the satisfactions that he intrinsically wants. This is a very basic contrast. In the older schools of psychology we have the characteristic sequence: the stimulus—the person— the behaviour. The behaviour is thought of mainly as replies to the stimuli. In the newer schools of psychology we have a different characteristic sequence: the person —the stimulus—the behaviour. The stimulus is treated merely as the environmental facts that we use to express our purposes.

2. STIMULUS-RESPONSE

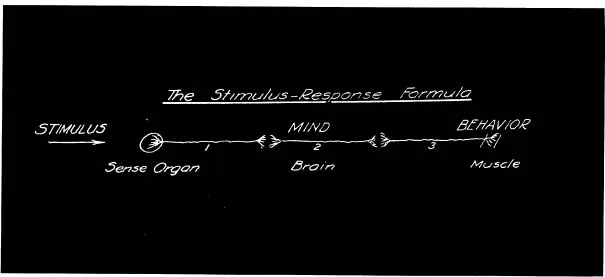

In the current academic psychology we teach a stimulus-response formula about which everything else psychological revolves. The contributions of the newer schools of psychology are certain to modify the rigidity of this formula. By the stimulus-response formula is meant the constant resolution of every psychological problem into three conventional parts: the stimulus, which is treated as a first cause, the mind or central nervous system, and the behaviour which is treated as a reply to the stimulus. After some practice this formula becomes so thoroughly ingrained that every psychological question is habitually broken up into a search for the provocative stimulus, a description of the resulting mental states, and a description of the responsive behaviour.

Fig. 1.

When a mental phenomenon is to be explained, many psychologists and educators of the older schools proceed somewhat as follows. What was the stimulus ? Describe it. What was the muscular response ? Describe it objectively. What happened between these two things ? There were “bonds” between them, and “pathways” and “grooves ”; and “processes” took place, and there were “connexions” in the nervous system between the stimulus and the response. That settles it, and the event is psychologically explained. In order to make it clear they draw three lines on the blackboard with “fuzzy” ends to represent neurones and synapses. (See Fig. 1.) The three parts of the conventional analysis are represented diagrammatically by three neurones, one for the sense organ which receives the stimulus, one or more representing the central nervous system, and one representing the innervation of a muscle. Here we have the basic formula for psychological analysis as it is currently taught. Behaviour or conduct begins with a stimulus, and it ends with a muscular response. One cannot read the authors who represent the findings of abnormal psychology without becoming sceptical about the adequacy of this stimulus-response formula to which we have long been accustomed, although none of these writers explicitly attack the formula as such.

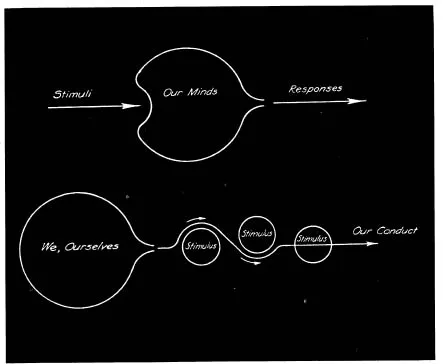

In Fig. 2 the two contrasting points of view are represented in a diagrammatic way. The generally current formulation is represented in the upper part of the diagram. A stimulus hits us. The mind consists of the so-called bonds and pathways, and out comes the response. When we see a muscular adjustment, we point to a known, or unknown, stimulus which has found its way transformed through bonds and pathways into our conduct. It would hardly be fair to say that we are always as totally unmindful of the mental in our mental science as the simple diagram would indicate. And yet, the great majority of discussions in psychology are carried out with this formula, either explicitly or by implication. To the student who approaches the study of psychology in expectation of discovering how his mind works, it is often a legitimate disappointment for him to learn that psychologists have reduced his mind to three unmental categories, the external physical stimulus, or the physiological stimulus, the bonds and pathways which dispose of everything mental, and the physical muscular behaviour. To relegate habitually our mental life into the unmental stimulus-response categories is a procedure which carries the appearance of science in its terminology, but which is not infrequently indicative of a superficial and unsympathetic understanding of mental life.

In the second part of Fig. 2 I have represented the function which, it seems to me, the stimulus really serves. Let us start the causal sequence with the person himself. Who and what is he ? What is he trying to do ? What kind of satisfaction is he trying to attain ? What are the types of self-expression that are especially characteristic for him ? What are the drives in him that are expressing themselves in his present conduct ? Consider the stimuli as merely the environmental facts in terms of which he expresses himself. In the diagram I have represented the causal sequence as starting with the dynamic living self. Self-expression is defined into particular actions at the terminal end of the diagram. The environment, the stimulus, is causally intermediate. The stimulus determines the detailed manner in which a drive or purpose expresses itself on any particular occasion.

Fig. 2.

In the diagram I have attempted to show that the stimuli may be considered as of three kinds with respect to the life impulse of the organism. First, we have the stimuli that promise satisfaction of an impulse. These stimuli call forth acts of appetition. Second, we have the stimuli that mean failure. These stimuli call forth acts of aversion. Both of these types of stimuli are perceived as significant and they are determinants of conduct. Third, we have the stimuli which are entirely indifferent with respect to the impulses of the organism. These stimuli call forth no variation in conduct. If, while walking to your office in the morning, you see a coal-wagon in front of you on the sidewalk, it is a stimulus which determines an avoiding reaction. It is antagonistic to your purpose of the moment. When you see your office door in front of you it determines a positive reaction because it becomes a part of your purpose at that moment. Most of the signs, stores, vehicles, and people are indifferent stimuli which are not even perceived because you do not identify them with your purpose at the moment. In the diagram are represented two stimuli which cause avoiding reactions, and a stimulus which causes a positive reaction. The stimuli which are indifferent to the impulse or purpose are not represented in the diagram because they are not even perceived.

It is also possible to describe your actions according to the first formula. It is possible to say with accuracy that you have a visual impression of the coal-wagon, and that you respond to its presence by dodging it. The stimulus is then placed first, and your behaviour is said to be a response to the coal-wagon stimulus. The temporal sequence of such a description is correct. You first see the wagon, and then you dodge it. This is stimulus and response. It is apparent that both of these formulae may be used with some justice to the facts. It is preferable to use the second formula because it is much more powerful as an explanatory device for complex conduct. It must be remembered that even though the stimulus precedes the response, there is usually present a purpose or objective before the appearance of the stimulus.

There are situations in which the appearance of the stimulus is sudden, and in which there cannot be said to have been any conscious purpose before the appearance of the stimulus. Such is the case when suddenly you jump out of the way in response to a Klaxon horn. You do not then have a conscious purpose to jump before the sound becomes focally conscious. The stimulus appears to be the first cause in such a situation, and it would seem to be primarily provocative of the response. It would seem to fit the first formula better, but a second consideration would bring out the fact that we are always in readiness to maintain our physical, social, financial, professional selves. To be in constant readiness to maintain, defend, and promote the self, in all its aspects, is the very essence of being alive. That is exactly the difference between an organism that is alive and one that is dead. We are so accustomed to this fundamental characteristic of every waking moment, the readiness to maintain the living self, that we do not notice it as a provocative cause for the things we do to maintain it. The Klaxon horn can then be thought of as merely the environmental circumstance at the moment by which you express that which was a part of you before the sound appeared. The sound merely determines the detailed manner in which you maintain yourself at this particular moment.

3. THE DYNAMIC SELF

In the last analysis the datum for psychology is the dynamic living self and the energy-groups into which it may be divided. We may refer to this datum as the Will to Live, or we may call it the Life-impulse, or the Vitality of the organism, or we may discover it to be the energy released by metabolism. We may be able to subdivide our will to live into large energy-groups which manifest themselves in conduct more or less independently. These energy-groups would be our innate, dynamic, and more or less distinct sources of conduct, and we might come to call them drives, motives, instincts, determining tendencies, or any other word that represents that which we as individuals innately really are, that which characterizes us as persons with individually preferred forms of life.

The living self consists of impulses to action, and the conflicts of these impulses. The conscious self I have thought of as made up of impulses that are for some reason arrested while partly formed, incomplete impulses that are in the process of becoming conduct. By this I do not mean that conscious life is different from conduct, that conscious life is merely associated with conduct by any bonds or connexions. I mean that conscious life is made of the same stuff that conduct is made of. The only difference between an idea and the corresponding action is that the idea is incomplete action. Focal consciousness consists of, is actually made of, the impulses that are in the process of becoming conduct. The aggregate of these impulses, this incomplete conduct, constitutes the momentary"me The permanent and more or less predictable characteristics of these impulse...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 The Stimulus-Response Fallacy in Psychology1

- Chapter 2 The Classification of Behaviour

- Chapter 3 Mind as Unfinished Conduct

- Chapter 4 Stages of the Reflex Circuit

- Chapter 5 The Principle of Protective Adjustment

- Chapter 6 The Preconscious Phase of The Reflex Circuit

- Chapter 7 Overt and Mental Trial and Error

- Chapter 8 Inhibition and Intelligence

- Chapter 9 The Sense Qualities

- Chapter 10 Autistic Thinking

- Chapter 11 The Function of Ineffective Adjustments

- Chapter 12 A Definition Of Intelligence

- Summary