![]()

CHAPTER I

SOCIAL OUTLINE OF KAMPALA

Kampala’s Development

Kampala lies just north of the Equator, to the north-west of Lake Victoria, about six miles from the Lake itself. It enjoys an altitude of some 4,000 feet above sea level and a pleasant, equable climate, a dominant feature of which is the frequent showers of heavy rain. The seasonal variations are slight. There are no real rainy seasons, and temperatures rarely rise above 30°C. during the day or fall below 16°C. at night. Kampala and its environs are amply provided with green and lush vegetation all the year round.

It is a commercial, administrative and communications centre, with a substantial minority of small-scale manufacturers. The growth of industry has been especially conspicuous since 1946, due mostly to high sales of cotton and coffee after the war and also to the accompanying development of engineering factories and enterprises producing a whole range of consumer goods.

Since Uganda’s independence in October 1962, Kampala has been the nation’s official capital. In effect, it has always been Uganda’s commercial capital and, through the years, has gradually assumed from Entebbe the position of administrative capital.

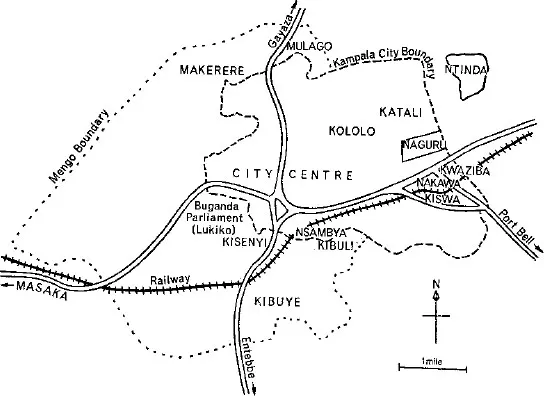

At independence, too, Kampala became a city. The city may be regarded as one of the two main areas which together make up a single urban agglomeration. The other area is Mengo Municipality which accommodates the palace and parliament of the former kingdom, now region, of Buganda and is its capital. The whole agglomeration may be referred to as Kampala-Mengo,1 which is rather more precise than the older term, Greater Kampala.

Mengo Municipality lies to the west and south of Kampala city. Though adjacent, Mengo and Kampala are administratively highly distinct. Service benefits in Mengo for a long time lagged behind those in Kampala. With the old capital of Buganda kingdom acting as a focus, and with a degree of economic specialization made possible by a cash-crop economy and individual land tenure, settlements of what is now Mengo arose spontaneously in a very self-sufficient manner to accommodate a whole range of migrants from professional to unskilled, with a preponderance of the latter.2 Except for a very high status elite, mostly Ganda, the pattern of life in Mengo is of people moving fairly frequently from one room to another, and into and out of different areas. These movements would appear to constitute an element in a general pattern of internal movement in Kampala-Mengo as a whole.

The élites of Mengo and Kampala are highly involved. But Mengo has its own distinct system of relations. Though Mengo provides much of Kampala’s labour force, many of Mengo’s residents are self-employed and contribute towards its partial economic and social self-sufficiency. Most of these residents are of the local tribespeople, Ganda, whose customs and institutions have come to be accepted and imitated by certain other tribespeople.3

Until recently Europeans and Asians were politically dominant in Kampala, while Ganda were dominant in Mengo. In the years immediately after the Second World War, housing estates to the east of Kampala municipality were built. They were established on Crown land and administered by the Uganda Government. In 1956 they were brought into Kampala itself. This extension of the Kampala municipal boundary most clearly marks the beginning of what is at present a rapidly increasing political and social integration of Africans into their nation’s capital.

The second major historical landmark in this process of integration was the decision in March 1962, by the Minister of Local Government of the then internally self-governing Uganda Democratic Party, that a larger proportion of municipal councillors were in future to be elected by popular vote. Up to this time all town council members had been appointed by the Governor, or by the Minister of Local Government during Uganda’s short period of internal self-government. Now there was to be the election of councillors on a political party basis. The Uganda political parties are the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC), the present ruling party, and the Uganda Democratic Party (DP). The Ganda Kabaka Yekka Party (KY) established a coalition with the UPC during the 1962 national elections.

For the purpose of its council elections Kampala was divided into three wards, Kampala South, West and East. The two former are still mostly European and Asian high-status residential areas, though an increasing number of high-status Africans have taken up residence in them. Kampala East is the one dominantly African area. It is the area of the housing estates. In the Kampala municipal elections of 1962, the potential power and effectiveness of Kampala East’s population as leaders and voters was obvious. African candidates and elected were in the majority for Kampala East, while Asians were still in the majority in the other two wards. In Kampala East, Kenya African migrants had provided much of the drive in this ward’s political activity.

By the time of the Kampala city council elections of February 1964, all persons who were not Uganda citizens were disfranchised. This disfranchisement included not only European and Asian non-citizens but Kenya Africans as well. A further clause disqualified non-resident property-owners, including many Ganda. The city elections of February 1964, therefore, concerned a much smaller number of people than in 1962. All three wards were indeed represented by a greater proportion of Africans to non-Africans, though the political drive and activity of 1962 were lacking. The point remains, however, that the population of Kampala East, as it stands, is one which is aware of the current demand for the greater political and social Africanization of a town like Kampala in an independent African State like Uganda. In contrast, with the exception of an indeterminate number of mostly Ganda of high status, the people of Mengo are largely disinterested in the problem of how quickly Kampala city may come under the greater commercial and social, as well as political, control of its African residents.

Why should the African population of Kampala East, most of whom live in city council housing estates or areas, be differentiated in this way?

In 1956, Southall and Gutkind noted the popularity of the estates in the long waiting lists for houses on them. They noted also that the population in the estates was above the socio-economic average for the African population in Kampala-Mengo as a whole. Their hypothesis was ‘that the estates will in the long run cater principally for the non-Ganda whose skill and income is above the average level and who appreciate a more secure and conventionally respectable existence than is at present possible for those who rent rooms in suburbs such as Kisenyi or Mulago’ (the two areas intensively described and analysed by the authors).4 Eight years after the statement, at least, it is possible from the evidence of my data to say that this hypothesis has been borne out. It was these authors who first drew attention to the developing tripartite structure of Kampala-Mengo, in which, in addition to the older duality of Kampala and Mengo, the people on the housing estates were emerging as a distinctive category in special relationship to both Mengo and Kampala municipality of which they were part.

Kampala-Mengo

According to the 1959 census the total population of Kampala-Mengo was 107,058. According to the census of 1948 it was 62,264. Even allowing for the fact that Kampala-Mengo in 1959 included the extension into Crown land of Kampala East, the overall increase in population is reasonably pronounced. The increases in non-African population are from 14,324 in 1948 to 26,800 in 1959 for Asians, and from 1,497 to 3,539 for Europeans. The increase for Africans alone is from 46,443 to 76,719. It is interesting to note that Europeans, followed by Asians and then Africans, have shown the greatest proportional population increase during these years, and after, even though this was a period of Africanization immediately prior to independence. Indeed, as some following figures show, the same period has seen a considerable decline in African labour.

The increase in African population from 1948 to 1959 is largely due to labour migration. The officially enumerated Kampala labour force itself increased from 29,381 in 1952 to 38,023 in 1957, declining to 36,635 and 27,878 in 1958 and 1961.5 While the population of Kampala-Mengo has not dropped and is probably even higher than the 1959 census figures, the number of wage-earning employees listed by the government department of labour had dropped considerably in the year before independence. Fewer jobs were then available, and the wide-scale unemployment had already given cause for alarm.

Yet, in the estates of Kampala East, the number of unemployed is relatively low. Few household heads are unemployed, and it is relatives who are seeking work or have just lost jobs and who may be lodging with them who are likely to constitute the majority of unemployed in the ward.

MAP 1

KAMPALA — MENGO

The 1959 census also gives figures indicating the distribution of persons according to rather arbitrary age-groups in Kampala, Mengo, and Kampala-Mengo as a whole.

| % | % | % |

| under 16 | 16–45 | over 45 |

| Kampala | 25∙8 | 69∙0 | 5∙1 |

| Mengo | 31∙8 | 57∙9 | 10∙3 |

| Kampala- Mengo | 29∙9 | 61∙5 | 8∙6 |

| Uganda (estimated) | 43∙5 | 43∙7 | 12∙8 |

As might be expected, migrants in Kampala-Mengo fall mostly in the 16–45 age group. There are more of this age group in Kampala, presumably due to the larger proportion of migrant employees. In Mengo the greater proportions of old persons, especially, and also of children are related both to the large numbers of Ganda who have owned land and property in the area for a long time and to the general tradition of residence by Ganda families at the king’s capital.

Within the working age-group the proportions of males and females are:

| % | % |

| Males | Females |

| Kampala | 69∙9 | 30∙1 |

| Mengo | 6o∙6 | 39∙4 |

| Kampala- Mengo | 63∙8 | 36∙2 |

| Uganda | 48∙9 | |

The proportion of males to females is significantly higher in Kampala than in Mengo. Yet, as I shall illustrate, on the estates I studied in Kampala East, there is much less of this imbalance. But there are considerable variations in the adult sex ratio for individual tribespeople. I cannot reproduce the approximate proportions for the 16–45 age group but the general sex ratio according to tribe probably reflects the adult ratio. Thus, of the Ganda in Kampala-Mengo 50∙5 per cent are females, a ratio of females to males of 101∙9 per cent. The Ganda are the only tribespeople in Kampala-Mengo among whom females outnumber males. They are followed by the Soga and Nyoro, among whom the ratios of females to males are 76 per cent and 64 per cent respectively. The ratios for the Acholi and Jonam are 53.5 per cent and 50 per cent, but no other tribespeople have as many as half the number of females to males.

The average length of residence in Kampala by migrants is not given in the census, but Elkan puts it at abou...