eBook - ePub

The People of Aritama

The Cultural Personality of a Colombian Mestizo Village

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The People of Aritama

The Cultural Personality of a Colombian Mestizo Village

About this book

This book covers the life of a small Mestizo community in Columbia, with its people and institutions, its traditions in the past and its outlook on the future.

Chapters include:

· information on the health and nutritional status of the community

* discussion of formal education and certain sets of patterned attitudes such as those which refer to work, illness, food and personal prestige.

Originally published in 1961.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The People of Aritama by Alicia Reichel-Dolmatoff,Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Fundamental Conditions of Individual Existence

I

THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL SETTING

THE SIERRA NEVADA DE SANTA MARTA

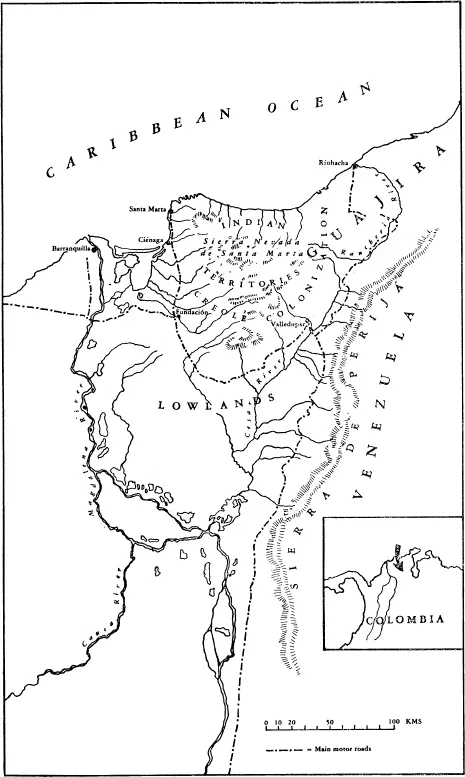

THE most outstanding physiographical feature of the Caribbean coast of Colombia is the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, an isolated mountain mass which rises abruptly from the tropical lowlands, between the delta of the Magdalena River and the northernmost extension of the Eastern Cordillera. Like a solitary island set between the dry deserts of the Guajira Peninsula and the green plains and swamps of the Lower Magdalena, this mountain massif covers approximately the third part of what is known as the Departmento del Magdalena, one of the twenty-four territorial districts which form the Republic of Colombia. With its highest peaks the Sierra Nevada reaches an altitude of 5,775 meters above sea level, which makes it the highest mountain in Colombia, but in proportion to its elevation its base is small, occupying an area, roughly triangular in shape, which measures not more than about 150 kilometers on each side.

Rising from the alluvial plains between the Magdalena River to the west and south, and the Ranchería and Cesar rivers to the east, this mountain is approximately pyramidal in shape. The steep northern slopes descend toward the Caribbean; the slightly less steep western slopes look toward the delta of the Magdalena River, and the gentle southeastern slopes face the Sierra de Perijá, a branch of the great system of the Colombian Cordilleras. The Sierra Nevada is separated from the Andes by the wide valleys of the Ranchería and Cesar rivers, both of which have their sources on the southeastern slopes, not far apart. But whereas the Ranchería River describes a wide curve toward the north and, at the end of its semicircular course, enters the sea near the town of Ríohacha, the Cesar River flows southward and joins the Magdalena near the town of El Banco. The watershed between the upper parts of the two rivers is hardly more than 200 meters high so that both drainages form a single, wide flood plain between the Sierra Nevada and the Cordillera of the Andes which, in this particular region, bears, from south to north, various names: Sierra de Perijá, Serranía de Valledupar, and Montes de Oca.

To the south of the Sierra Nevada there extend the wide lowland plains, interrupted here and there by low hills, reaching down to the immense, semiaquatic region which borders the Magdalena River, with its innumerable lagoons, backswamps, and oxbow lakes. To the same general region pertains the vicinity of the Ciénaga Grande, a large inland sea separated from the Caribbean by a narrow, sandy strip of land, the Costa de Salamanca, which extends between the mouth of the Magdalena and the little town of Ciénaga, south of the departmental capital, Santa Marta.

From these fertile alluvial plains abruptly rise the first foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Except for a stretch along the northern slopes where the forest reaches down to the coastline, the first elevations are covered with thorn scrubs. Then the ‘dry forest’, with a fringe of humid forest along the streams, reaches to about 500 to 700 meters altitude. From there on the humid forest extends to the lower limit of the paramos, the tundra-like summit plateaus which lie between 4,000 and 4,500 meters and above which the snow begins. This zonification can be observed best on the western slopes but it is not as clear in the southeast, where large extensions are covered with savannas, reaching sometimes to 2,000 meters altitude. These grassy savannas, interrupted here and there by small forests or fringes of dense vegetation, lend very special characteristics to this southeastern part of the Sierra Nevada, distinguishing it from the other slopes where there is denser forest. On the northern side the humid forest covers almost the entire extension from the seashore up to 3,000 meters, but here also occasionally appear small savannas which cover the principal valleys. The tropical zone covers the largest part of the total area, reaching in the Sierra Nevada to about 1,300 meters, an altitude which corresponds approximately to the upper limit of the low cloud layers. The subtropical zone follows, reaching to about 2,500 meters, where the temperate zone begins, which, in turn, is limited by the paramos at 3,500 or 4,000 meters. About 1,000 meters higher begins the snowline.

But climate and vegetation, and with them, the general aspect of the mountain, change not only according to altitude but also in relation to the geographical orientation of the slopes. The entire Caribbean coast of Colombia, between the Guajira Peninsula and the mouth of the Magdalena River, lies under the trade winds, which blow from the northeast during several months of the year, violently and continuously, reaching the Sierra Nevada after having passed over the sandy expanses of the Guajira desert. The southeastern slopes are, therefore, the most exposed to these winds, and so offer the characteristic aspect of grassy savannas and shrub covered ridges and hills, while higher trees and small forests occur only along the streams or in the mountain folds which are protected from the trade winds. The northern slopes and, to a lesser degree, the western slopes, which are less exposed to the winds, are covered to a greater extent with true forest.

In the entire Caribbean lowlands of Colombia only two yearly seasons can be distinguished: the rainy season or ‘winter’ (invierno), which begins late in April and lasts through November or to the beginning of December, and the dry season or ‘summer’ (verano), which lasts from December to April. A short intermediate period of little rainfall in June and July is called ‘little summer’ or veranillo. During the rainy season heavy showers fall almost every day except in the semiarid regions of Santa Marta, Ríohacha, and some of the lower valleys in the southeast where precipitation is less marked and where occasionally weeks may pass without rain. During the dry season, on the other hand, the rains stop completely. The months of heaviest rainfall are May and October. Depending upon the orientation of the three slopes of the Sierra Nevada, precipitation varies considerably. The driest region is the southeastern slope, which is exposed to the trade winds, whereas the northern and western slopes are relatively wet.

The geographical isolation of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta imposes a certain biological and cultural isolation upon life, an isolation which can be observed to have existed since prehistoric times. Situated on a crossroad of aboriginal migrations, provided with permanent streams, arable land, abundant fish in both the sea and the inland lagoons, it is only natural that this solitary mountain, visible at great distances, should have caught the attention of migrating tribes and attracted them. Remains of their ancient cultures have been found everywhere, in hundreds of sites which dot the valleys and hills. Potsherds, remains of large architectural complexes built of stone, agricultural terraces, slab-paved roads, petroglyphs, and much other evidence of ancient cultures bear testimony to the Sierra Nevada’s having been peopled since remote times by human groups who chose this mountain and its valleys for a temporary or permanent habitat. However, archeology has not yet succeeded in establishing a chronological sequence of these cultures, following them through time and space since their earliest beginnings. Most remains studied so far date from relatively recent periods and show a highly developed culture, the earlier phases of which are still largely unknown.

Although archeologists have hardly begun to decipher this abundant record of the past, many characteristics of a culture of Regional Florescent type are obvious. The ancient Indians lived in large nucleated villages of several hundred houses each, the foundations of which were constructed with carefully dressed or cut stone. A network of roads and bridges, stairs and trails, all built of stone slabs, covered the mountain folds, connecting these centers and allowing their inhabitants to travel easily from one valley to the other, from one slope to the adjoining, from the coast to the highlands. Agricultural terraces provided with irrigation ditches covered large areas. Society was stratified and directed by secular chieftains and priests, the latter beginning to exercise almost absolute authority. Two incipient ‘states’ had begun to take shape from alliances between numerous villages under the leadership of individuals. Metallurgy, pottery, and the stonecutter’s craft had reached a level only rarely equaled by other pre-historic cultures of Colombia. This, then, was the aboriginal culture the Spaniards found when they first discovered the Sierra Nevada.

The first Europeans to see these mountain peaks rising over the plains of the South American mainland were the soldiers and sailors of Rodrigo de Bastidas, in 1501. Bastidas explored the coast between the Guajira Peninsula and Panama, visited several of the beaches at the foot of the northern slopes of the Sierra Nevada, discovered the Magdalena River, and established the first contacts with the natives. After him came other explorers and conquerors. Alonso de Hojeda, Rodrigo Hernández de Colmenares, Martin Fernandez de Enciso, the expedition of Pedrarias Dávila—all followed this coast and took back the first news of the Sierra Nevada and its inhabitants. But they hardly ever left the safety of their ships, preferring to trade with the Indians for gold and pearls without trying to explore their hostile land.

But in 1521 the Spanish Crown decided to take possession of and explore this coast and Rodrigo de Bastidas, who by then had become a resident of Santo Domingo, was named by the Council of the Indies governor of the unknown lands lying between the Guajira and the mouth of the Magdalena. After long preparations, Bastidas landed in the Bay of Santa Marta in 1525, where he took formal possession of the land and founded what proved to be the first Spanish settlement, calling it Santa Marta. From here Spanish troops entered the valleys, penetrated to the highlands, explored the coast. The loot of gold and pearls, and the slave trade, which produced huge profits in the Antilles, were powerful incentives, but so was the zeal to convert the Indians to the Christian faith. The Spaniards quickly realized that a region which could sustain thousands of inhabitants in large villages, with thousands of men who were masons, agriculturalists, and navigators, was an excellent place for large-scale colonization. So the conquest of the fierce Tairona Indians, creators of this highly developed culture, was begun.

During their first encounters the Indians had shown little resistance and had received the Spaniards well. But soon this situation changed. The establishment of the first encomiendas, the abuses committed by their administrators and the soldiers, and the pressure brought to bear by missionaries who tried to suppress the aboriginal religion, began to cause serious difficulties. The Indians organized their resistance and practically the entire sixteenth century, from 1525 to 1599, was passed in bloody battle for possession of the lands to the east and south of Santa Marta.

In 1599 the governor, Don Juan Guiral Velón, led the Spanish forces in a war of extermination. Condemning all native chieftains to death at the stake or the gallows, the governor ordered their houses and fields burned, and their villages sacked by his troops. At this price peace was finally obtained, but the land had been devastated and the human element that had made it productive had been eliminated or dispersed. By the middle of the sixteenth century, many of the coastal villages had already been abandoned, their inhabitants having sought refuge in less accessible regions. The paved roads that in former times had been maintained by the communal labor of the villages they connected had become covered by the jungle. The villages themselves had fallen into ruins, because their inhabitants had fled, or had fallen victims to new epidemic diseases or to the blades of Spanish troops. The large maize fields which had been burned had overgrown with forest. When at last, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Velón laid waste the Sierra Nevada, the Spaniards found themselves masters of jungle and ruins— the flourishing villages, with their fields, their roads, their numerous and active people, having disappeared.

And so the Sierra Nevada was abandoned again. Not a single Spanish village established in the mountains by force during the sixteenth century survived this war. The focus of colonization was transferred instead to the banks of the Magdalena River, to the littoral, and to the interior of the country. Even the town of Santa Marta almost disappeared. Burned to the ground by Indians and fugitive Negro slaves, sacked by English, French, and Dutch pirates, its inhabitants decimated by epidemics and isolated from other centers of Spanish colonization, the town barely survived the centuries of conquest and colonization and, in spite of its excellent harbor, lost its former importance. Not until the beginning of the twentieth century, with the advent of large-scale plantation and exportation of bananas, did there begin a new period of growth and development for Santa Marta. Even now for the most part Santa Marta continues its somnolent and provincial ways, overshadowed by the great commercial town of Barranquilla and the walls and fortresses of Cartagena of the Indies.

While the sixteenth century, which had seen the conquest of the Sierra Nevada with Spanish troops penetrating its most hidden valleys, is well documented, the seventeenth century remains almost a blank in the history of this region. Perhaps because of the wars that Spain was waging against her continental enemies or because of the Inquisition or for some other historical reason, there exist very few data on colonizing or missionary activity in this part of Colombia. It is known that there still existed a few encomiendas with a small number of Indians; that there were a few Indian parishes or villages whose inhabitants paid tribute to the Crown, but little is known of the processes and impacts of contact between the native culture and the Spanish overlords from 1600 to 1700.

For the eighteenth century, however, there is more concrete information. The archives and the Spanish chronicles of this period give many details on missionary activity among the surviving Indians of the Sierra Nevada and occasionally contain valuable data on colonization and aboriginal culture. From these sources it appears that during the eighteenth century the missionaries, mainly friars of the Franciscan community, again penetrated the valleys, establishing missions in several villages, building chapels, and bapti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyrights Page

- Original Copyrights Page

- Contents

- Plates

- Preface

- Introduction

- PART I. FUNDAMENTAL CONDITIONS OF INDIVIDUAL EXISTENCE

- I. THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL SETTING

- II. THE BIOPHYSIOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS

- III. THE SOCIOPSYCHOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS

- PART II. SPECIFIC INSTITUTIONAL FORMS OF SOCIAL LIFE

- IV. FORMS OF SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

- V. FORMS OF PRODUCTION AND PROPERTY

- VI. FORMS OF DISTRIBUTION AND LABOR

- PART III. CULTURAL CONFIGURATIONS OF REALITY

- VII. DIMENSIONS OF THE NATURAL

- VIII. DIMENSIONS OF THE SUPERNATURAL

- IX. DIMENSIONS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

- X. SUMMARY

- APPENDIX: CURES FOR DISEASES

- INDEX