![]()

PART ONE

THE FACE OF MONASTICISM

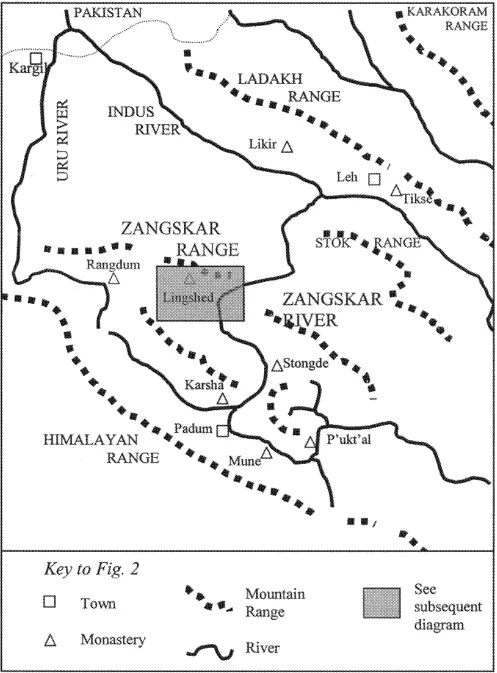

FIGURE 1 Ladakh and Zangskar on the South Asian map (for inset see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 Kumbum’s surrounding towns and monasteries in Ladakh and Zangskar.

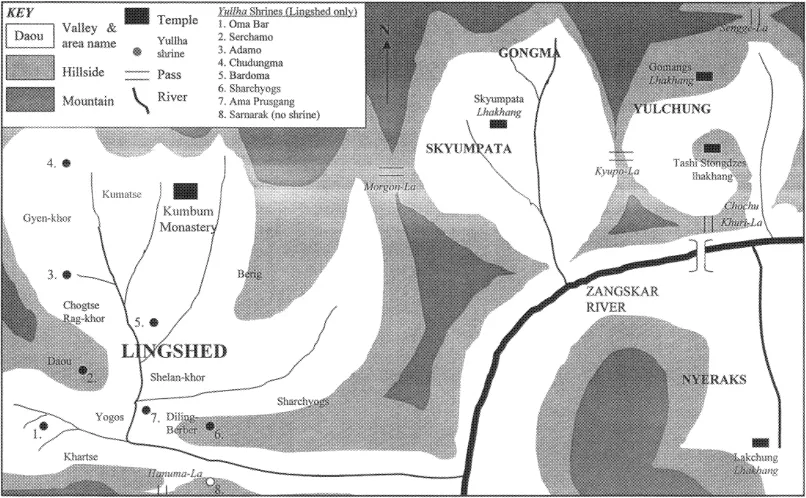

FIGURE3 The Trans-Sengge-La Area – Lingshed and its surrounding villages.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

HISTORY AND AUTHORITY

There are none left to be trained by me. Because there are none left for me to train, I will demonstrate the way to nirvana to inspire those who are slothful to the doctrine and to demonstrate that what is compounded is impermanent. The snowy domain to the north [i.e. Tibet] is presently a domain of animals, so even the word ‘human being’ does not exist there – it is a vast darkness. And all who die there turn not upwards but, like snowflakes falling on a lake, drop into the world of evil destinies [i.e. the hells and so forth]. At some future time, when that doctrine declines, you, O Bodhisattva, will train them. First, the incarnation of a Bodhisattva will generate human beings who will require training. Then, they will be brought together [as disciples] by material goods. After that, bring them together through the doctrine! It will be for the welfare of living beings!

Addressed to the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara by the dying Buddha Sakyamuni (Kapstein 1992: 86)

THE VIEW FROM ABOVE

If one were travelling from Leh – the regional capital of the Ladakh region of north-west India, on the very border of Himalayan Tibet1 – to Kumbum Monastery in the summertime, traversing the 5000 metre Trans-Sengge-La Pass once most of the snow had melted away, Lingshed village and its surrounding communities would seem to be nestled within a vast cauldron of mountains, criss-crossed with mountain spurs that point down towards the fast flowing waters of the Zangskar River. As one descends from the pass above Lingshed village itself, and passes clockwise around one of its many entrance cairns (chorten, S. stupa), the layout of almost the entire village greets one in a single vista, spread out in deep greens and yellows across the valley, nestled on ridges and slopes, built up with evident care around a fan of tumblingmelt water streams that descend from mountain waterfalls and braid together into a single tributary at the valley floor, flowing out of the village through the gorge that leads south to the Zangskar River.

During the winter months, when the high passes of the Zangskar Range become impassable with snow, this river acts as a vital lifeline between Lingshed and the surrounding areas of Ladakh and Zangskar: normally virtually unnavigable, the water’s surface freezes solid along much of its length in temperatures plummeting to –45 C, transforming the Zangskar River Gorge into a treacherous but passable ice-road, referred to as the chadar. Through this route, traders carry winter supplies of yak-butter, tea and medicines into and out of the snow-bound villages of the region, sleeping in frozen caves at night, and braving the changeable and often treacherous surface of the ice by day.

Within Lingshed valley, almost every available spot of land that can be viably used, is; these marks of human habitation separate the village off from the comparative desolation of the areas between. Unlike many villages in Ladakh and Zangskar – which cluster their houses together into lonely cliff-top citadels – the houses of Lingshed are dotted about on all sides of the main and subsidiary valleys, interspersed with fields of barley and peas, fed by intricate canals and miniature streams, distributing carefully negotiated quantities of precious water to ensure another year’s harvest for the village’s 400 inhabitants. The houses are mud-brick constructions varying in size from the larger khangchen (‘great houses’) where the young household head and his or her family live, to the smaller subsidiary dwellings called khangbu (‘offshoot houses’), inhabited by elderly grandparents or celibate lay-nuns.

If entering the village from the East, Kumbum Monastery itself is hidden behind a deceptive curve in the hillside, only becoming visible once the hour-long trek down the mountainside is almost complete. Once in full view, however, its physical presence is impressive, draped across a south-facing mountain slope in long hanging lines of monastic quarters, or shak (literally, ‘pendant’) that taper down from the central temple complex at its peak. In the sharp Himalayan sunlight, the crisp edges of the whitewashed monastery buildings are broken up by the maroon robes of monks going about their business, hurrying to prayer in the main temple, studying texts or entertaining the many laity that visit the monastery. Especially on the numerous ‘holy days’ of the year, the corridors and courtyards of the monastery buzz with life, and monastic quarters are filled with the chatter of monks’ various friends and relatives come to visit, bringing food, swapping news or requesting rites to be performed in the village. Physically separated from the village though Kumbum may be, it is hard to overcome the impression that it remains the social crossroads of the area.

One of the many lower-ranking monasteries of the Gelukpa order of Tibetan Buddhism, Kumbum is neither very large nor very important, especially by comparison with the vast monastic universities that flanked Lhasa in the days of old Tibet, or the new and highly politicised monasteries of the Kagyu and Gelukpa orders that, at the time this account was being written, were becoming the nerve centres of Tibetan Buddhism’s growing influence in the post-industrial cultures of Europe, America and East Asia. Lacking a resident incarnate lama to attract wealthy patrons, and disconnected from the hubs of South Asian economic life by high passes traversed only by mule tracks, and bitterly cold, isolating winters, Kumbum and its resident monks nonetheless do their job, serving the agricultural communities that surround it, and continuing a Buddhist tradition of monasticism whose origins can be traced back to the time of Sakyamuni Buddha, four centuries before the birth of Christ.

Although this book will range across a variety of issues – the nature of authority and truth in Tibetan Buddhist ritual, the role of incarnate lamas and the religious, political and legal ideologies that constituted Tibetan systems of statehood – it is also a book about Kumbum monastery and its surrounding villages, and the everyday activities of daily ritual life which dominate the lives of ordinary monks. To understand such local level events, and the processes that brought them into being, we must also look to the larger picture: in contrast to the ethnographic assertions of many early anthropologists and South Asian specialists, it is impossible to understand the village life of places such as Lingshed in isolation from the wider histories and political, social and economic flows that flood over it. Most clearly, it is impossible to understand the kind of religious life practised in Tibetan Buddhist communities such as Lingshed and Kumbum, without looking deep into its own, and Buddhism’s, past.

Before looking at that history, a few words of caution are required. One of the central difficulties of writing any anthropological work about Tibetan Buddhist monasticism comes in attempting to encapsulate the sheer volume of history that stands behind its various institutions and traditions. For many ‘modern’ thinkers – both Tibetan and Western – such histories have two particular manifestations: the ‘objective’ histories of the archaeologist and secular historian on one hand; and the interpretative histories of Buddhist self-representation on the other. Generally, these two are seen as at odds, with the former acting to progressively deconstruct and disprove the pious and post hoc reconstructions of the latter, unearthing the ‘true’ history of Buddhism to its (presumably conservative and indignant, but ultimately ‘enlightened’) proponents. After all, as we shall see in this chapter, the religious history of Buddhism, both at its source in India, and in its later manifestations in Tibet, is replete with tales of magical feats and battles, of miraculous powers and divine interventions, a cacophony of superstitions and improbabilities that are anathema to many modern, rational commentators, Buddhist or otherwise.

From the perspective of the anthropologist, however, the situation is more complex. Whilst the findings of archaeologists and Buddhologists aid in the production of historical accounts of the transformation of institutions, the manner in which Tibetan Buddhists in Lingshed monastery, Lhasa or Dharamsala seek to represent their own history is itself part of that very objective history. Indigenous historical accounts give crucial insights into the manner in which people perceive themselves now as inheritors of such histories, and elaborate the meanings and significances behind crucial activities and ritual actions. As Geshe Ngawang Changchub – head scholar and principal teacher in Kumbum – explained to me once when I expressed some doubt as to the confidence that could be placed in historical claims made by deities when they ‘possessed’ local individuals, the purpose of historical accounts from a Buddhist perspective lay not in their simple factual accuracy, but in their ability to generate faith in Buddhism – something which was, to his mind, of greater benefit than the dry technicalities of ‘objective’ history. In what follows, therefore, I have attempted to balance the kind of historical information agreed on by secular historians, and more ‘legendary’ accounts of historical process. Both, I believe, have a place in any understanding of the present.

THE ORIGINS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM

Within the vast history of Buddhism in Asia, Tibetan Buddhism was a relative late-comer. As the doctrines and practices of Gautama Sakyamuni, the Buddha (‘Awakened One’) spread from their place of origin in Kosala and Magadha in North India, Buddhism’s power and influence flourished with enormous speed, spreading swiftly along the trade routes of Asia in the centuries following his death and paranirvana in 483 AD2 influencing and transforming the histories and states of Northern India, East and South East Asia. The deserts and valleys of Tibet, locked within the mountainous walls of the Himalaya, Karakoram and Kunlun mountain-ranges, were by contrast left as an empty hole in the heart of Buddhist-dominated Asia. Even the influence of the vast Kushan (or Mauryan) empire, under the Buddhist Emperor Asoka (r. 270–240 AD), centred on the very doorstep of Tibet’s Western flank in modern-day Kashmir, failed to make substantial inroads into the high plateau. The Tibetan regions of the time were barren and politically fragmented wastelands, populated by nomadic herders, brigands and local warlords, whose religious life was dominated by local mountain worship and other earth cults. This heterogeneous indigenous ritual life is now often subsumed under the wider rubric of Bon – centred principally on the priestcraft of local deity worship.

It was not until the middle of the seventh century AD that the military expansion of Central Tibet’s Yarlung kingships brought local ruler...