eBook - ePub

A Breton Landscape

From The Romans To The Second Empire In Eastern Brittany

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Breton Landscape

From The Romans To The Second Empire In Eastern Brittany

About this book

First Published in 1997. This is a case study of changing land-use patterns in Brittany over nearly 2000 years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Breton Landscape by Wendy Davies,Dr Grenville Astill,Grenville Astill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

THE APPROACH

CHAPTER 1

The problematic

Looking at East Brittany in 1978, when we began work there, its rural communities of small farmers appeared timeless: strongly agricultural, committed to their localities, with limited external connections, living beside their work, and farming the land in a mixed regime. We knew, because of our familiarity with ninth-century texts, that this land was well peopled and intensively used before the year AD 1000, with an apparently similar mixed agricultural regime. Had there been no change?

In the first instance, therefore, we posed these questions: has land-use in eastern Brittany changed during the historic past, that is in the period since records began in northern Europe? Has the organization of human settlement in relation to the land changed during those two millennia? And if so, how, and how much, and when, and why?

Since there are no series of maps across the millennia, nor photographs, nor statistical data like that collected by the French state in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, we thought hard about how to investigate change. Was it possible to use some of the approaches that have characterized prehistoric studies in the past couple of decades? Could modern field survey methods contribute anything that was not recoverable from documents?

In the second instance, therefore, we posed the question of how to establish a viable methodology for such a study.

Given each author’s background of both historical training and archaeological experience, to draw upon written and archaeological data was obvious. But how to marry the two was not at all obvious. So, thirdly, we set out to test the parameters of interdisciplinary work. We wanted to explore the interface between documents and fieldwork: how easy (and how useful) is it to correlate several (and different) classes of evidence? Can one ever be a viable control on the other?

Figure 1.1 The present landscape in the survey area: a view towards Carentoir, from the southwest

These, then, were the three problem areas that we set out to address: how much did land-use change in eastern Brittany in the last 2,000 years; how can such a set of issues best be investigated; and how far can useful interdisciplinary work be done?

We decided to look – at micro-level – at an area that had both good documentation across a long period and also the potential for an archaeological programme of extensive field survey. At an early stage, observing both the rate of decay of standing buildings and the resource that they offered for investigating sixteenth- to twentieth-century change, we also included a systematic study of standing structures in the area.

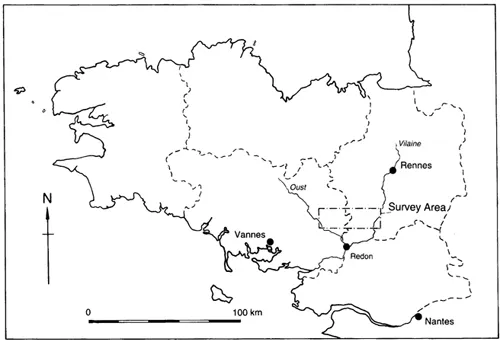

We chose the Oust–Vilaine watershed, in the Département of the Morbihan (Fig. 1.2). This allowed us to investigate a well-used landscape, in no way “marginal” or “peripheral” in the archaeological sense, with plenty of land under plough, giving us an opportunity to exploit modern fieldwalking techniques to the full. It is an area well supplied with written source material, from the early middle ages to the twentieth century, with a particularly rich corpus of localizable material relating to land-use from the later middle ages and early modern period.

Figure 1.2 Location of the survey area

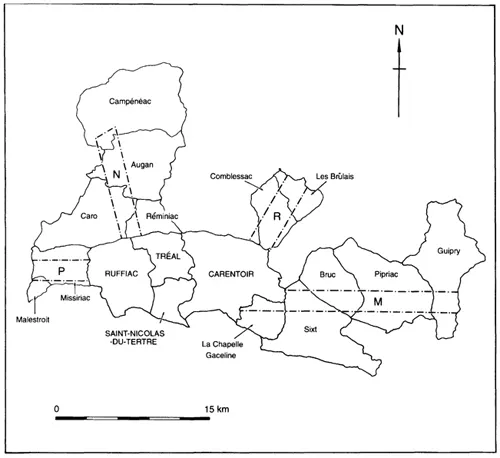

The project focussed on an area of 128 km2, the four communes of Ruffiac, Tréal, Saint-Nicolas-du-Tertre and Carentoir, as a core for intensive study, with the communes surrounding the core sampled to take in the whole of the watershed. Sampling was organized by taking four transects, to north, east and west: Transect P ran west to the River Oust and Transect M ran east to the River Vilaine; Transects N and R ran, respectively, northwest and northeast (Fig. 1.3).

The landscape of the late twentieth century is gently undulating, open, with small patches of tree cover, some coniferous plantations and isolated trees – particularly fruit-bearing apple trees and pollarded chestnuts (see Fig. 1.1). While small streams are common throughout, it is only the larger valleys of the Vilaine, the Oust and its tributary the Aff that strike the attention of the visitor. There are very few permanent boundaries: large arable fields dominate the landscape although zones of pasture and temporary grassland occur too. A prominent menhir in Ruffiac, a modest alignment in Carentoir and a couple of dozen stone crosses (especially of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century date) remind us of the human past, but it is the number of settlements that signals the ubiquitous presence of people in this landscape (Gouézin 1994: 102, 48; Ducouret 1986).

Figure 1.3 The survey core, with sample transects

At the time of the survey, in the 1980s, settlements in the core comprised the four principal villages or bourgs (the commune centres) and 348 subsidiary farms and hamlets: despite the central nucleations, a strongly dispersed pattern, with hardly anywhere more than 500m from a settlement; it is a pattern that is repeated in the sample transects. Carentoir, at 59.02 km2, was by far the largest of the four communes, with a population of 2,495 in 1990; Ruffiac followed, at 36.47 km2 and 1,381 inhabitants; then Tréal at 19.28 km2 and 632 inhabitants, and Saint-Nicolas at 12.93 km2 and 454; densities of population were therefore low, at between 33 and 43 inhabitants per km2 (see further below, pp. 55–6, 52).1 The nearest market towns are Malestroit, at the western end of Transect P and 3 km west of the Ruffiac border; La Gacilly, 1½ km south of the Carentoir border; and Guer, 6 km north of the Carentoir border. Though Guer is larger than the other two, all these are small towns, with populations of between 2,000 and 6,000. The capital of the Département, Vannes, lies 35 km to the southwest, on the coast; the regional capital, Rennes, lies 45 km to the northeast; and the town of Redon lies 18 km to the southeast.

Figure 1.4 Rangée at Triguého (Tr)

The survey area is notable for its distinctive vernacular architecture and for the use of siltstone orthostats (large upright slabs) as walling, both in buildings and in property boundaries. The buildings are, typically, single-cell dwellings, with ground floor living quarters and storage loft above, usually arranged in south-facing rows (rangées) of anything from two to twelve houses (Fig. 1.4). There are also some more substantial houses, petits châteaux, with implicit or explicit aristocratic associations, especially of early modern date (see Fig. 7.8) – often accompanied by walled garden and courtyard, with farm buildings and dovecot, and a landscaped aspect from the front of the house. Long-houses, with byre as well as domestic residence, and a common lateral doorway, are also notable. Some of the latter were converted into two-cell domestic dwellings in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; plenty of two-cell dwellings were built afresh in the same period, while bungalows and modern two-storey multi-cell houses (typically built on mounds on the outskirts of settlements) characterize post-war housing. Other recent construction includes pig and poultry units, and modern farm buildings, whose number has increased noticeably since 1978.

*********

It did not take long to discover that the aura of timelessness that first impressed us was completely misleading: the rate of change through the 1980s was all too evident; the briefest look at the maps of the Napoleonic cadastre revealed a landscape that had been very different a hundred and fifty years before; and the visible decay of standing buildings suggested both changing settlement patterns and a once-larger population.

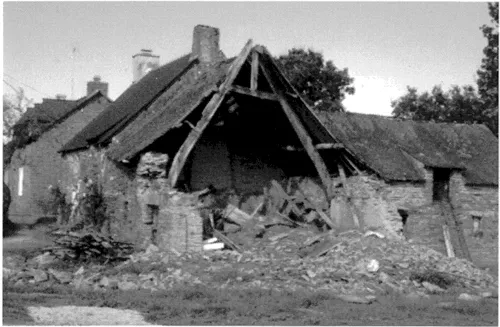

Figure 1.5 Collapsing building at Bois Neuf (Saint-Martin-sur-Oust)

The image of the roofless and collapsing house has often been used to characterize inland Brittany and inland problems in the late twentieth century. It is an instant symbol of rural depopulation, of the desertion of the countryside and decline of local employment. Of course, the roofless house is a powerful image – but we think it is more powerful than it is useful. As we discovered, houses have collapsed and been left to rot for centuries; this is no new development of the late twentieth century. People forget that rebuilding happens close by and the collapsing house is part of a continuum of occupation. And although there certainly has been a decline of population in inland Breton communes, that decline can be as much a reflection of dynamic relationships and new opportunities as of dying communities (see below, pp. 52–4). Witness the 19 British families now domiciled in Ruffiac.

Rural Brittany has seen, and continues to see, a great deal of change. What is interesting is the relationship between the changing and the unchanging; as also what causes the changes and what makes them happen when they do: internal dynamic, external influence, or combinations of the two?

CHAPTER 2

Method and methodology

This project was planned as a multi-disciplinary study. While drawing on the techniques of a range of specialists, the principal methods used were gathering and analysis of written data from archive collections, a staged programme of archaeological fieldwork and a systematic survey of standing buildings in the core communes. At an early stage of the project we also went through all the then available (high level and oblique) aerial photographs; and in 1996 we consulted the recent photographs taken by Maurice Gautier. Both early (1980–81) and late (1995) we consulted the records of existing sites and previous archaeological activity in the region; these were originally housed in the archives of the Direction des antiquités de Bretagne at Brest but are now at the Service régional de l’archéologie de Bretagne, in Rennes (hereafter SRAB).1 We made no more than a modest use of place-name evidence since, although there are many excellent studies, place-names are difficult to use for microhistory when there are no, or few, dated early name forms.

Archives

The corpus of texts specific to the core communes and sample transects begins in the early middle ages with the collection of charters in the Cartulary of Redon. This is an eleventh-century collection of (largely) ninth-century documents about properties in southeastern Brittany in which the monastery of Redon had an interest (Davies 1990a); most of the properties lie north of Redon, and within 40 km of the present town. At least 65 of these...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- PART 1: THE APPROACH

- 1 The problematic

- 2 Method and methodology

- 3 Context

- PART 2: CHANGING LAND-USE IN THE LANDSCAPE OF EAST BRITTANY

- 4 Romans and provincials

- 5 The problem of the early middle ages

- 6 Nobles and peasants

- 7 Landscaping

- 8 Rising population

- 9 Work and housing

- 10 After the Revolution

- 11 The Longue Durée

- Bibliography

- Notes

- Index