- 370 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Methods In Language Processing

About this book

Studies in Computational Linguistics presents authoritative texts from an international team of leading computational linguists. The books range from the senior undergraduate textbook to the research level monograph and provide a showcase for a broad range of recent developments in the field. The series should be interesting reading for researchers and students alike involved at this interface of linguistics and computing.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Analogy-based methods

1

Skousen’s analogical modelling algorithm: a comparison with lazy learning

1.1 Introduction

Machine learning techniques may help in solving knowledge acquisition bottlenecks in natural language processing. Instead of hand-crafting linguistic knowledge bases like rule bases and lexicons almost from scratch for each new domain, language, application, and theoretical formalism, we can apply machine learning algorithms to a corpus of examples, and automatically induce the required knowledge.

This paper explores one such class of algorithms, “lazy learning” (LL), for which there has been an increased interest in machine learning recently. In this type of similarity-based learning, classifiers keep in memory a selection of examples without creating abstractions in the form of rules or decision trees. Generalization to a new (previously unseen) input pattern is achieved by retrieving the most similar memory items according to some distance metric, and extrapolating the category of these items to the new input pattern. Instances of this form of “nearest-neighbour method” include instance-based learning (Aha et al. 1991), exemplar-based learning (Salzberg 1991; Cost & Salzberg 1993), and memory-based reasoning (Stanfill & Waltz 1986).

The approach has been applied to a wide range of problems using not only numeric and binary values (for which nearest-neighbour methods are traditionally used), but also using symbolic, unordered features. Advantages of the approach include an often surprisingly high classification accuracy, the capacity to learn polymorphous concepts, high speed of learning, and perspicuity of algorithm and classification (Cost & Salzberg 1993). Aha et al. (1991) have shown that the basic instance-based learning algorithm can theoretically learn any concept whose boundary is a union of a finite number of closed hyper-curves of finite size (a class of concepts similar to that which decision-tree induction algorithms and neural networks trained by back-propagation can learn). Training speed is extremely fast (it consists basically of storing patterns), and classification speed, while relatively slow on serial machines, can be considerably reduced by using indexing mechanisms on serial machines (Friedman et al. 1977), massively parallel machines (Stanfill & Waltz 1986), or wafer-scale integration (Kitano 1993).

In natural language processing, LL techniques are currently being applied by various Japanese groups to parsing and machine translation under the names “exemplar-based translation” or “memory-based translation and parsing” (Kitano 1993). In work by Cardie (1993) and by the present authors (Daelemans 1995; Daelemans et al. 1994), variants of LL are applied to disambiguation tasks at different levels of linguistic representation (from phonology to semantics).

One LL variant, “analogical modelling” (AM) (Skousen 1989) was explicitly developed as a linguistic model. On the one hand, despite its interesting claims and properties, it seems to have escaped the attention of the computational linguistics and machine learning communities, while on the other hand, the AM literature seems to be largely oblivious of the very similar LL and nearest-neighbour techniques. In this paper we provide a qualitative and empirical comparison of AM to the more mainstream variants of LL.

In the next section the concept of LL is elaborated further and a basic lazy learner is described. A number of improvements to that basic scheme will be discussed. Next, AM is presented in considerable detail. We will then turn to the main theme of this paper: a comparison of the basic lazy learner and AM. This comparison will mainly focus on two aspects: (a) the global performance of both algorithms on a selected linguistic task, and (b) the algorithms’ resistance to noise: the performance of the algorithms is monitored in conditions in which the learning material contains progressively more “noise”.

1.2 Variants of LL

LL is a form of “supervised learning”. Examples are represented as a vector of feature values with an associated category label. Features define a pattern space, in which similar examples occupy regions that are associated with the same category (note that with symbolic, unordered feature values, this geometric interpretation does not make sense). Several regions can be associated with the same category, allowing polymorphous concepts to be represented and learned.

During training, a set of examples (the training set) is presented in an incremental fashion to the classifier, and added to memory. During testing, a set of previously unseen feature–value patterns (the test set) is presented to the system. For each test pattern, its distance to each example in memory is computed, and the category of the least distant instance is used as the predicted category for the test pattern.

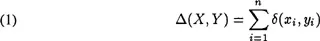

In LL, performance depends crucially on the distance metric used. The most straightforward distance metric would be the one in (1), where X and Y are the patterns to be compared, and δ(xi,yi) is the distance between the values of the ith feature in a pattern with n features.

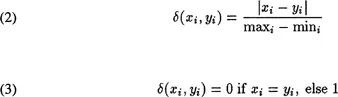

Distance between two values is measured using (2) for numeric features (using scaling to make the effect of numeric features with different lower and upper bounds comparable), and (3), an overlap metric, for symbolic features.

1.2.1 Feature weighting

In the distance metric described above, all features describing an example are interpreted as being equally important in solving the classification problem, but this is not necessarily the case. Elsewhere (Daelemans & van den Bosch 1992) we introduced into LL the concept of “information gain”, which is also used in decision tree learning (Quinlan 1986, 1993), to weigh the importance of different features in a domain-independent way. Many other methods to weigh the relative importance of features have been designed, both in statistical pattern recognition and in machine learning (Aha (1990) and Kira & Rendell (1992) are examples), but the one we used will suffice as a baseline for the purpose of this paper.

The main idea of “information gain weighting” is to interpret the training set as an information source capable of generating a number of messages (the different category labels) with a certain probability. The information entropy of such an information source can be compared in turn for each feature to the average information entropy of the information source when the value of that feature is known.

Database information entropy is equal to the number of bits of information needed to know the category, given a pattern. It is computed by (4), where pi (the probability of category i) is estimated by its relative frequency in the training set.

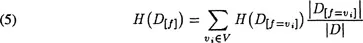

For each feature, the information gain from knowing its value is now computed. To do this, we compute the average information entropy for this feature and subtract it from the information entropy of the database. To compute the average information entropy for a feature (5), we take the average information entropy of the database restricted to each possible value for the feature. The expression D[f = vi] refers to those patterns in the database that have value vi for feature f; V is the set of possible values for feature f. Finally, |D| is the number of patterns in a (sub)database.

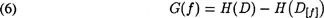

Information gain is then obtained by (6), and scaled for use as a weight for the feature during distance computation.

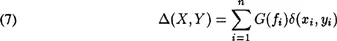

Finally, the distance metric in (1) is modified to take into account the information gain weight associated with each feature (7).

1.2.2 Symbolic features

A second problem confronting the basic LL approach concerns the overlap metric (3) for symbolic, unordered feature values. When using this metric, all values of a feature are interpreted as equally distant from each other. This may lead to insufficient discriminatory power between patterns. It also makes impossible the well-understood “Euclidean distance in pattern space” interpretation of the distance metric. Stanfill & Waltz (1986) proposed a “value difference metric” (VDM) which takes into account the overall similarity of classification of all examples for each value of each feature. Recently, Cost & Salzberg (1993) modified this metric by making it symmetric. In their approach, for each feature, a matrix i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Part I: Analogy-based methods

- Chapter 1 Skousens analogical modelling algorithm: a comparison with lazy learning

- Chapter 2 Analogy, computation and linguistic theory

- Chapter 3 Constraints and preferences at work: an analogy-based approach to parsing grammatical relations

- Part II: Connectionist methods

- Chapter 4 Towards a hybrid abstract generation system

- Chapter 5 Recurrent neural networks and natural language parsing

- Chapter 6 Learning the semantics of aspect

- Chapter 7 Experiments in robust parsing with a Guided Propagation Network

- Chapter 8 Learning semantic relationships and syntactic roles in a simple recurrent network

- Part III: Corpus-based methods

- Chapter 9 A system for automating concordance line selection

- Chapter 10 A machine learning approach to anaphoric reference

- Chapter 11 Some methods for the extraction of bilingual terminology

- Chapter 12 Probabilistic part-of-speech tagging using decision trees

- Chapter 13 A new direction for sublanguage NLP

- Chapter 14 Efficient disambiguation by means of stochastic tree-substitution grammars

- Part IV: Example-based Machine Translation

- Chapter 15 Towards automatically aligning German compounds with English word groups

- Chapter 16 Corpus-based acquisition of transfer functions using psycholinguistic principles

- Chapter 17 A natural-language-translation neural network

- Chapter 18 Direct parse-tree translation in co-operation with the transfer method

- Part V: Statistical approaches

- Chapter 19 Evaluating the information gain of probability-based PP-disambiguation methods

- Chapter 20 Automatic error detection in part-of-speech tagging

- Chapter 21 A method of parsing English based on sentence form

- Chapter 22 A new approach to center tracking

- Chapter 23 Structuring raw discourse

- Part VI: Hybrid approaches

- Chapter 24 Coarse-grained parallelism in natural language understanding: parsing as message passing

- Chapter 25 A stochastic GovernmentBinding parser

- Chapter 26 Evolutionary algorithms for dialogue optimization as an example of a hybrid NLP system

- Chapter 27 More for less: learning a wide covering grammar from a small training set

- Part VII: Methodological issues

- Chapter 28 Software reuse, object-oriented frameworks and NLP

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access New Methods In Language Processing by D. B. Jones,H. Somers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.