- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 2001. As an architect and ornamentist by profession, the author of this volume has specialist knowledge of many manufacturing processes and presents his observations on architectural edifices and Japanese art. Includes photos and commissioned drawings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Japan by Christopher Dresser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

JAPAN:

ITS ARCHITECTURE, ART, AND ART MANUFACTURES.

PART I.

CHAPTER I.

Yokohama—The Grand Hotel—Sights in the Streets—Jinrikishas—Japanese hospitality —Sachi—Yedo, or Tokio—Letter-writing—The Castle—Winter in Japan—Temple of Shiba—Tombs of the Shôguns.

IT was on the 26th day of December at 6.30 in the morning that I first saw Japan. As yet this strange country was enveloped in a soft mist above which the sun was only just rising, but as the mist dispersed we could see that the land was pleasantly undulating and richly wooded ; that in some of the valleys, fissures, and gorges nestled little picturesque villages ; that in sheltered spots palm-trees, with their plumous tops, rose high above the houses that found shelter beneath them, and that junks of quaint aspect ploughed the shallow waters of the coast.

A cry arises from the Japanese passengers, who are earnestly looking to the left (for we have several on board) —Fujiyama! I look in the direction in which they gaze, but see no mountain. The undulating land in front is perfectly distinct, and is thrown out on a background of gray-and-white cloud which rises high behind it ; but I see no mountain. Under the guidance, however, of Japanese friends, I look above these clouds, and there, at a vast height, shines the immaculate summit of Japan’s peerless

B

cone. I have seen almost every alpine peak in the land of Tell ; I have viewed Monte Rosa from Zermat, Aosta, and Como ; I have gloried in the wild beauty of the Jungfrau and the precipitous heights of the Matterhorn ; but never before did I see a mountain so pure in its form, so imposing in its grandeur, so impressive in its beauty, as that at which we now gaze. I do not wonder at the Japanese endowing it with marvellous powers ; I do not wonder at this vast cone around which clouds love to sleep being regarded as the home of the dragon—the demon of the storm,—for surely this mountain is one of nature’s grandest works !

Rounding a promontory we soon enter the bay of Yokohama, fire two cannon, and drop our anchor.

In a few minutes certain officials come on board, and the ship is surrounded by a score of native boats. Some belong to hotels, some seek to take passengers or merchandise on shore, some bring out servants of the company to which our ship belongs, and others a variety of things which it is impossible to describe. A scene of life and activity thus springs up around us of a character so novel as to be both interesting and amusing. A small steam-launch is now moored to the side of our great vessel, and General Saigo, the commander-in-chief of the Japanese army, who is on board, invites me to step into the launch and accompany him on shore : the launch is a Government boat which has been sent to convey the General to land.1 Accepting the kind invitation I am soon seated in the boat, where we find the son of the General, who is a cheerful smiling-faced urchin about two years old. No sooner does the father see the little fellow than he caresses him with that warm affection which the Japanese at all times show towards their children ; but there is no kissing, for kissing is unknown in the East, and while the General manifests his love for his child I yet feel that the little fellow has not received all his due, and I almost long to kiss him myself. The screw of our little launch is soon in motion, and in a few minutes I stand on a land which, as a decorative artist, I have for years had an intense desire to see, whose works I have already learned to admire, and amidst a people who are saturated with the refinements which spring only from an old civilisation. With the view of reaching my hotel I now get into a jinrikisha, a vehicle somewhat resembling a small hansom cab, only with a hood that shuts back. It is lightly built, has two somewhat large wheels, and slender shafts united together by a tie-piece near their extremities. It is drawn by a man who gets between the shafts and most ably acts the part of the best of ponies, or sometimes by two, or even three men. In the latter cases the tandem principle is adopted, and the leaders are attached to the vehicle by thin ropes. As soon as I am seated in my carriage, which is scarcely large enough to contain my somewhat cumbrous body, my tandem coolies (for I have two) set off with a speed which is certainly astonishing, if not alarming, and I soon find myself at the entrance to the Grand Hotel—a European house—where I secure my room (terms three and a half dollars or fourteen shillings a day, including everything save fire and wine).

Breakfast this morning was somewhat neglected, for the excitement of nearing land after a twenty-one days’ sea-voyage had lessened our appetites. It seemed impossible to spare time for a hearty meal when, with the movement of our vessel through the water, shifting scenes both strange and beautiful were constantly presenting themselves to our sight. The keen, fresh, exhilarating air, the cloudless sky, the bright and cheering sunshine, and the gallop through the wind in my tiny carriage had caused nature to assert itself and demand some refreshment for the inner man.

Sitting down to table at the hotel I partook of a somewhat hurried meal. Fish, entrées, and joint were presented in due sequence, as though I were sitting in the Grand Hotel at Paris ; while grouped on dishes were tins of Crosse and Blackwell’s potted meats, and Keiller’s Dundee marmalade and jam. I confess that while these luxuries were in the most perfect state of preservation, and in every sense enjoyable, I was disappointed in seeing such familiar forms of food instead of the tentacle of an octopus, the succulent shoot of a bamboo, the fin of a shark, or some other such natives dainties as I looked for.

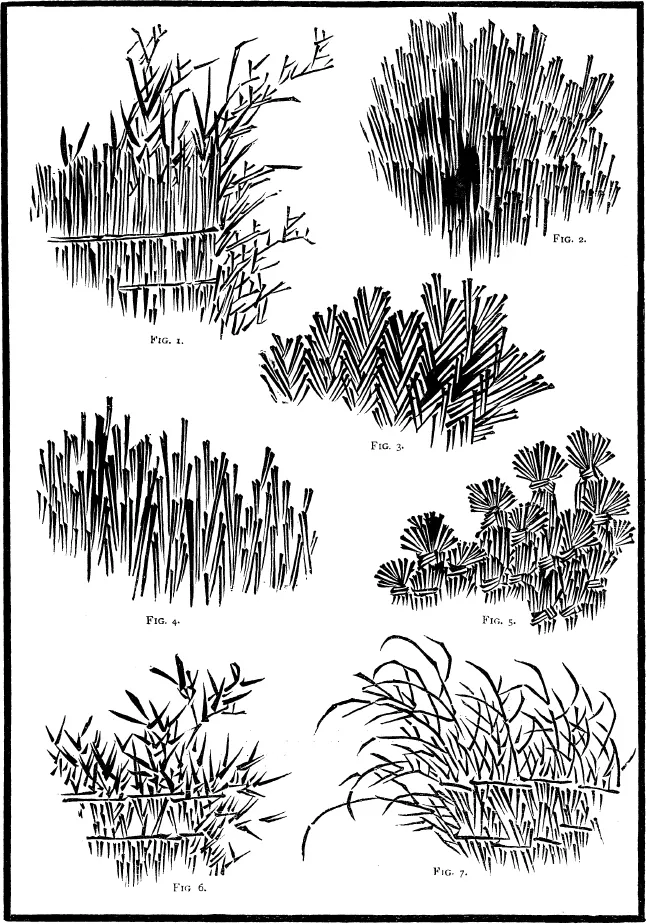

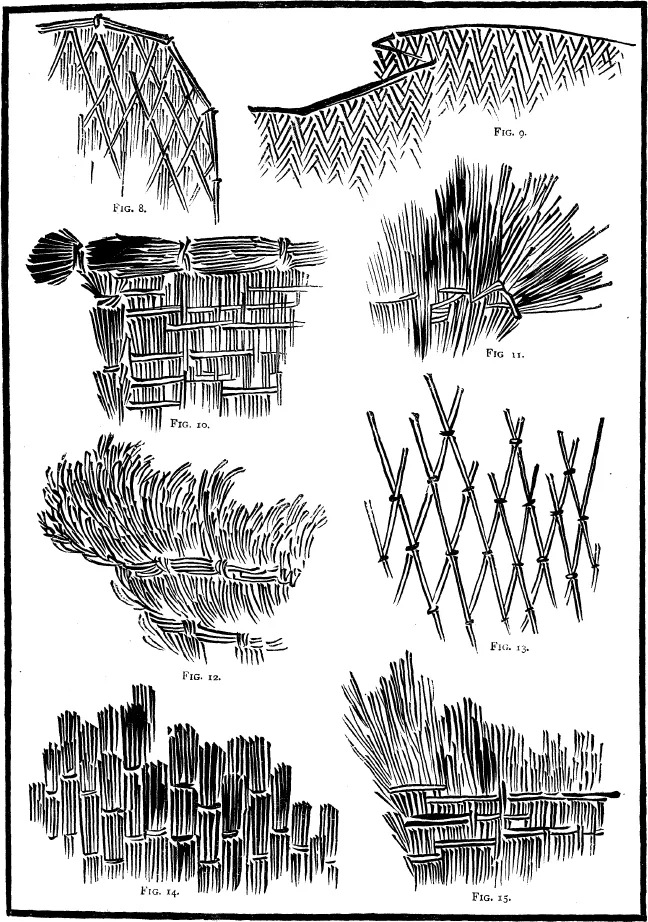

Having finished my meal, I am joined by a gentleman who is to act as my secretary while I am in the country, by Prince Henri of Liechtenstein, and by Prince Alfred Montenuovo (two Austrian princes with whom I have been a fellow-passenger from San Francisco), and we start for a walk, the secretary being our guide. We pass through the European settlement of Yokohama, where beautiful villas—in character half English and half Japanese —nestle in lovely gardens, and on to the native town. Here all is strange and quaint beyond description. The shops are without fronts and their floors are raised above the ground by one high step ; they are matted, and the goods are displayed on stands which resemble the so-called “stage” of a greenhouse. Strange articles of food, strange people, strange objects meet the eye on every side. We stop, we look, we admire, we wonder. We are looked at : smiles of amusement at the interest which is taken in things, to them common, meet us at every turn. We watch children play,—a little girl bounces a ball and turns round while the ball is ascending from the ground for her to hit again. We pass by a canal which is tunnelled through a hill, and on which the strangest of boats float ; we enter the precincts of a Buddhist Temple, but we must take our boots off before we cross the threshold. We return home by crossing “the bluffs,” from which we have a glorious view of the town and the bay, and by a road which, bordered by curious fences (Figs. 1 to 15), winds its way through nurseries where strange trees abound. I need scarcely say that we have enjoyed our walk more than words can tell. Indeed it would be almost impossible to describe the impression of novelty left on our minds ; but to give the reader some notion of the strange aspect of things I may repeat a remark made by one of the Austrian princes during the stroll. “Had we died,” he said, “and risen from the dead the scene presented could not be more strange.”

The princes dine with me, and at 8.30 we set out again ; this time in jinrikishas, each drawn by one man, who now bears a lantern, as it is dark, and off we go at almost the pace of a race-horse. We laugh heartily at the shouts of the men, the bobbing of the lanterns, the shaking of the vehicles, and the excitement of the furious run. In about fifteen minutes we alight in front of a large house, into one room of which we enter. Here our conductor orders for us a native repast, to which are to be added the pleasures of music and the dance. The room is a plain square, but there is European glass in the windows, and the doors have European fasteners. Mats cover the floor, and on the mats stand two brazen vessels (called hibachi), each containing a few bits of ignited charcoal ; and these primitive and insignificant fires afford the only means by which a Japanese room is warmed. We are favoured with Chinese chairs and two small tables, while the natives, who shortly come to serve the repast, or to amuse us by their music and dancing, kneel in front of us on the floor. Preparations having now been completed, a large lacquer tray is brought in, and placed in the centre of the group of kneeling female attendants. On this tray rests a dish of sliced raw, unsalted fish, with condiments of various kinds, all being arranged much like the French dish of Tête de veau vinaigrette if tastefully garnished with leaves. European plates are used out of compliment to us strangers, but chop-sticks are supplied instead of knives and forks. We taste the dish after many unsuccessful attempts at getting the food to our mouths by the aid of the chop-sticks, but strange to say, the viands have the flavours, and the condiments are almost tasteless. After the raw fish comes fried fish, and with it hot sachi.

Sachi, although generally regarded in England as a spirit, is in reality a white beer made from rice. Like all alcoholic drinks, sachi varies much in quality ; and the Japanese estimate its excellence by flavour, aroma, and other qualities, as we do our port and other wines. It is drunk both cold and warm, but it is not made hot by admixture with water, but is itself warmed ; and in this condition it is now offered to us.

NATIVE DRAWINGS OF THE FENCES WHICH BOUND GARDENS.

NATIVE DRAWINGS OF THE FENCES WHICH BOUND GARDENS.

Sachi cups are usually small earthen vessels of about two inches in diameter, much resembling in character shallow teacups, or deep saucers. They are without handle, and are offered to the guest empty after being placed in hot water for a few moments if he is to drink the sachi warm. Into these empty cups a second serving-maid pours the warm sachi from a delicately-formed china bottle.

Following the fish and the wine a dish of sea-slugs with herbs and sea-weed is served, but the mollusc is as tough as leather, and my powers of mastication are altogether overcome. After the repast, music begins with the samasin (banjo), and the coto (horizontal harp), together with certain drums (the tsudzumu and the taiko), while girls dance to the weird sounds—their motions being graceful but strange. This over, there is singing of native songs, after which we all leave, take our places in the jinrikishas, and are drawn home at almost lightning speed.

On the following morning I begin to make observations with some care. Yesterday everything was so new that impressions resulted chiefly from general effects, or curious incidents, while details were passed almost unnoticed. I now, however, seem to be more able to mark accurately what comes before me. Standing on the steps of our hotel, I glance upwards with the view of noticing the nature of the building in which I have for the present taken up my abode. To my astonishment what I yesterday regarded as a solid stone edifice turns out to be a mere wooden framework bearing on its surface thin slabs of stone, each of which is drilled partially through and is hung on two common nails.

This hotel is beautifully situated, having its chief face overlooking the sea, from which it is separated by a broad and well-made road. On its right is a canal which here meets the ocean. As I stand on these steps I have above me a cloudless sky of the deepest blue, an ocean rippled by the smallest of waves, and reflecting the azure of the heavens above. The white sails of picturesque boats reflect the rays of the sun, hidden from my view by the house in front of which I stand ; while the air has a crispness, due to the slight frost of the night, which makes it in the highest degree exhilarating. I breakfast off fish, ham, eggs, and tea, as though I were sitting at my own table in London, instead of being 12,000 miles from home, and then set out to view the shops and their contents. During my walk I find many curios that are to me quite irresistible, and I buy, I fear, in a truly reckless fashion. At 5.15 I return home somewhat tired, having had a perfect “field day” amidst the shops.

While I was dressing, Prince Henri came into my room and asked me to join him and Prince Montenuovo at dinner. Thus passed my second day in Japan.

I find the following scraps noted in my diary under date December 27th. It is customary here to go to a shop to select a number of goods, and then to ask the owner to send all the objects selected to your house, or hotel, for you to look over and decide upon at your leisure.

The people here are most polite and charming ; at one place while we were making purchases tea was served to us. The tea is by no means strong, is pale yellow (almost amber) in colour, and is drunk without milk or sugar. It is served in small cups without handles or saucers.

The native town of Yokohama is lit with gas, while the European quarter has at night dark streets. The foreign settler objects to a gas rate.

The next morning I go by appointment to Yedo (Tokio, or the northern capital) by 9.34 train. The railway connecting Yokohama (the port of Tokio) with Tokio is eighteen miles in length, is well built, and is one of two railways now existing in Japan ; the other railway connects Hiogo (Kobe) with Kioto (the southern capital). The Yokohama railway is of specially narrow gauge, and the carriages are more like omnibuses than any to be found on our lines—being small in size and entered at the end. A train leaves Yokohama for Tokio, and Tokio for Yokohama, every hour of every day in the year, and every train carries mails ; hence, while Yedo and Yokohama are eighteen miles apart, there is a delivery of letters in both places every hour of every day.

These places, and indeed all the towns of Japan, are now connected by telegraph wires, by the agency of which messages can be sent in the native character or in most of the European languages ; but for conveying a message in a strange tongue an extra fee is very reasonably demanded.

...Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Part I.

- Part II