![]()

Chapter 1

In London under James I

The London weavers in the seventeenth century lived in and around a crowded city, bustling and noisy, lying in a crude crescent along the north bank of the Thames from Wapping to Westminster. Its length was barely six miles and it was some two miles from north to south. Along the south bank of the river, linked to the City by London Bridge—the only bridge—lay Southwark, a pulsating extension of London, in shape like a finger and thumb pointing across marshes and meadows towards Kent and the Continent. The ‘Stately Thames enriched with many a flood’, gliding on ‘with pomp of waters unwithstood’, was then the City’s main highway; the most safe and speedy of routes, much used by Londoners of all classes upon all occasions, commercial, social and ceremonial; and by visitors from abroad, many of whom came upstream from Gravesend by river ferry-boats.

The tidal estuary of the ‘river of Thames’, says Stow, is the best way, ‘by which all kind of Merchandise be easily conveyed to London, the principal storehouse and staple of all commodities within this realm; so that omitting to speak of great ships and other vessels of burthen, there pertaineth to the cities of London, Westminster and borough of Southwark, above the number, as is supposed, of 2,000 wherries and other small boats, whereby 3,000 poor men, at the least, be set on work and maintained’.1 All day and every day these small boats—the water-taxis of the seventeenth century—threaded their way between the busy hoys,2 deep-laden lighters and moored merchant vessels, along and across the river, picking up and setting down passengers at the various stairs, piers and landing-stages. There were even ferries with platforms to take a coach and horses.

Elizabethan and Stuart London, though small by modern standards, was to the people of the seventeenth century an enormous city, both absolutely and relatively. By comparison with other cities and towns in the British Isles, London stood forth as fabulously rich and populous. In 1597 a government document estimated that the City of London’s rights to ‘measurage of commodities’ brought into the Port of London was worth as much as all similar rights throughout the whole of the rest of England.3 Another estimate is that, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, three-quarters of the country’s foreign trade paid toll in the London customs house.4

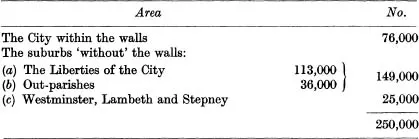

At the turn of the century (c. 1600) London’s population5—city, liberties and suburbs—was probably around 225,000 (or a quarter of a million if one includes Westminster, Lambeth and Stepney) distributed as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 The population of London c. 1600

No other city or town had one-tenth of that number of inhabitants. For instance, the City of Norwich with its out-parishes, a leading manufacturing centre in the seventeenth century, had, at most, 17,000 inhabitants,6 or less than one-fifteenth of the number in London and its environs. Furthermore, London’s rate of growth was quite remarkable by comparison with the other cities and towns of the kingdom. Although the birth-rate in London was low and the death-rate appallingly high, because of frequent outbreaks of bubonic plague and other epidemics, the City and suburbs—especially the latter—were continually refilled by immigrants from the provincial towns and the countryside, far and near, and from continental countries, France and Holland in particular. The metropolis was a mighty magnet pulling people, including great numbers of young people,7 from every direction. It attracted men of status and substance as well as those seeking their fortunes; the affluent, the ambitious, the innocent boy-apprentices and the smart Alecs ‘full of cozenage’, as Shakespeare (the best eyewitness we could wish for) tells us:

Disguised cheaters, prating mountebanks,

And many such like Liberties of sin.

There were, also, refugees from persecution and from justice—’people of desperate fortunes’. ‘At length they all to merry London came’, pushing and crowding in, ‘an immense concourse of men and animals’ multiplying the pressing evils of bad housing and primitive sanitation, pestilence, poverty and crime, and creating a perpetual nightmare for the authorities, both central and local. Only by continuous large-scale immigration could London’s population have increased at such a rate that the estimated 250,000 of the year 1600 had become an estimated 320,000 by 1625, and 600,000 by the end of the century.8

In Elizabethan and early Jacobean times London remained essentially a medieval city in which noblemen, merchants, craftsmen and shopkeepers lived side by side, hard by the haunts of criminals and the hovels of the poor. It was just a jumble of buildings large and small, magnificent and mean; residential, industrial and commercial premises; public buildings; churches set in ‘little green churchyard’ burial grounds shaded by stately trees; and—to astonish the stranger —many ‘fair gardens’ like Sir John Hart’s, where flowers and fragrant herbs and even fruit could be seen.9 All this (and much more) was tightly compressed within the ancient defensive wall, with its eight massive gates—Aldgate, Bishopsgate, Moorgate, Cripplegate, Alders-gate, Newgate, Ludgate and Bridge Gate. The monks and friars, it is true, had long disappeared from the streets, their great clusters of monastic buildings having been seized and turned to other uses.

The old walled city had overflowed to form a number of ‘liberties’10 and suburbs which were for the most part nothing better than closely built, noisome slums, huddled immediately ‘without’ the walls,11 extending outwards from the edge of the city ditch, which was originally some 200 feet broad and part of the medieval defences, but ‘now of later time’ (says Stow) ‘. . . is enclosed and the banks thereof let out for garden-plots, carpenters’ yards, bowling allies and divers houses thereon built, thereby the city wall is hidden, the ditch filled up, [only] a small channel left, and that very shallow’: in places it had become ‘a filthy channel’.12 The famous Dr William Harvey (15761657), discoverer of the circulation of the blood, lived in London during James I’s reign and remarked upon ‘the filth and offal . . . scattered about’ and the ‘sulphureous’ coal smoke ‘whereby the air is at all times rendered heavy, but more so in the autumn’.

Along the few main roads leading outwards from the City gates an unplanned riot of ribbon-development—houses, cottages, sheds and workshops of all sorts and sizes; many constructed of weatherboards— was slowly eating its way towards the nearest villages, such as Bethnal Green and Shoreditch to the north-east, Mile End to the east, and Bermondsey and Lambeth to the south. The result, on both sides of the principal thoroughfares, was a nightmarish maze of ill-paved or unpaved entries, yards, courts, alleys and tortuous, narrow lanes, in which all sorts of activities, legitimate, shady and downright criminal, were carried on. Some of the old mansions and larger houses, abandoned to decay and dilapidation when, for any reason, their original owners moved away, were each divided into as many as twenty or thirty tenements, and soon became part of an unsavoury medley of ruinous rookeries, dirty lodgings, dram shops, inns, taverns and brothels. Coldharbour, the Earl of Shrewsbury’s great mansion on the south bank, was demolished in 1600 and ‘the site given up to small tenements at large rents’.13

In such liberties and suburbs—Cripplegate Without, Bishopsgate Without, Farringdon Without, Southwark—the majority of the respectable ‘householders’ were master craftsmen: weavers, felt-makers, tanners, wheelwrights, carpenters, coppersmiths, dyers, glovers and the like; each family, with servants and apprentices, all under the same roof, which usually covered their workshop and stores as well. The range and variety of London’s crafts were a wonder to behold; and as the decades passed the demand for living and working accommodation was intensified by the incessant immigration of ‘foreigners’ from the provinces and ‘strangers’ (aliens) from the Continent.

One of the weavers’ chief complaints was that ‘most of the poorest sort of strangers are packed and thrust up with their whole families within divers . . . tenements ... of very small and narrow compass. . . . Insomuch as the City and the Suburbs . . . are filled, pestered and much annoyed with many . . . troublesome and offensive Inmates.’14 All this resulted in rising rents which brought forth certain property ‘developers’—carpenters, bricklayers, plasterers and chandlers—who saw a chance to make easy money by buying up the leases of premises occupied, often for many years past, by weavers and other craftsmen, and ‘dividing of houses, erecting (upon new foundations) Sheds, Hovels and Cottages, putting into every room a family, to the great pestering of the City, Suburbs and places adjoining with Inmates, Aliens and Undersitters’.15

Such gross overcrowding in conglomerations of ill-ventilated wood-and-plaster dwellings, separated only by narrow lanes and alleys with kennels full of muck coursing down the middle; with polluted water supplies;16 with ditches and open sewers running this way and that, and laystalls heaped with rotting refuse in close proximity to the houses; all this was a terrible threat to public health, as the Weavers’ Company told the Lord Mayor in 1632, for (they said) it ‘brings with it an unavoidable danger to breed contagious and infectious diseases, if God should visit the same with any sickness or mortality’.17 They had, indeed, good reasons for their fears. The reign of James I was sandwiched between two severe outbreaks of bubonic plague (in 1603 and 1625) and there were a number of comparatively minor visitations in the intervening years. What neither the weavers nor anybody else knew was that the black rats that infested their houses and sheds carried fleas, and these were the deadly distributors of ‘the poor’s plague’, the ‘great sickness’, which so often struck down with swift ‘spotted death’ man, woman and child, regardless of rank or calling.

No doubt people’s resistance and resilience were buttressed by the widespread interest in ‘sports’ and contests (accompanied, of course, by gambling), and by the nearness of the countryside. The London populace, high and low, gentry and journeymen, merchants and master craftsmen, loved a fight in any form: cock-fighting, bull- or bear-baiting, fencing with swords ‘very little, if at all, blunter on the edge than the common swords are’, or a furious fracas between traditional enemies such as men of rival occupations. The Thames watermen, toughened by their ancient trade and masters of the most lurid language, were in every way formidable opponents of those competing upstarts, the coachmen of the ‘Hackney hellcarts’ or ‘four-wheeled tortoises’ so detested by John Taylor, the Water Poet;18 the butchers had a reputation for truculence and a readiness to resort to violence (which is, perhaps, not surprising), and even the weavers occasionally had their militant moments.19

It was a community in which men and women alike ate and drank heartily whenever they ...