![]()

XV

Scottish Mints

by IAN STEWART

[Plates XV–XIX]

INTRODUCTION

The study of mints is in many respects a subject almost as wide as coinage itself. In this paper I have generally confined myself to the consideration of where, when and why minting took place in Scotland; many other aspects of minting – in particular the administrative and technical – which could reasonably claim treatment under such a heading, have had to be limited to occasional references when relevant to the principal theme. Nevertheless, the paper has outgrown its original plan, since the more deeply I investigated the question of location and function of mints and the significance of obverse die-links between them, the more clearly I realised that previous studies of Scottish coinage,* including my own, were often far short of having provided a sufficiently exact analysis of the numismatic evidence. As a result, I have had to set out period by period – in sections III to VI – the framework and chronology of the earlier coinage in order to assess the occasion, duration and intensity of the activity of different mints. Overall it is an attempt to set numismatic analysis against the historical background, for neither alone is sufficient. Sometimes history will supply, with more or less certainty, an occasion – and thus both a date and an explanation – for an issue which could be dated only imprecisely on purely numismatic grounds; in other cases the evidence of the coins may stand alone, and only when die-analysis has established the anatomy of a coinage can the numismatist legitimately offer explanations of why or when individual mints took part in it. The inquiry is far from conclusive, and though some new answers are suggested to recognised problems, not only do others remain unsolved but new ones have been added to them: perhaps it is an example of the old lesson that one cannot even begin to find a solution until one asks the right question. I hope at least to have added some precision to the many questions which exercise those who study the mints and coinage of Scotland.

In form, the paper consists of eight parts. The first is a general discussion of the location and function of Scottish mints and the second a record of the way in which mint names occur on Scottish coins, with notes on each of the places at which they were or may have been struck. In the third, fourth, fifth and sixth sections, a narrative of the progress of medieval coinage in Scotland is given from the point of view of the mints involved, divided into the main periods of its development, the twelfth century, the Voided-Cross sterlings of the thirteenth century, the Single-Cross sterlings of the Edwardian era, and the later middle ages. The seventh section deals with the form and whereabouts of the Scottish mint after 1500. The final section discusses the general significance of obverse die-links, and all examples of such between Scottish mints that have so far been noticed are listed in an appendix; these links are referred to in the text by their serial numbers throughout the sections to which they relate.

Though all too hastily written, the work on which this paper is based goes back many years and owes much to the help and encouragement of Albert Baldwin, and in particular to the generous way in which he and other members of the family and firm to which he belonged have made available to me records of and material from the great Brussels hoard, which transformed our knowledge of the coinage at a period when more Scottish mints were active than ever before or afterwards. The catalogue compiled by his grandfather, the late Mr A. H. Baldwin, has been the starting point for all further study of the Alexandrian mints.

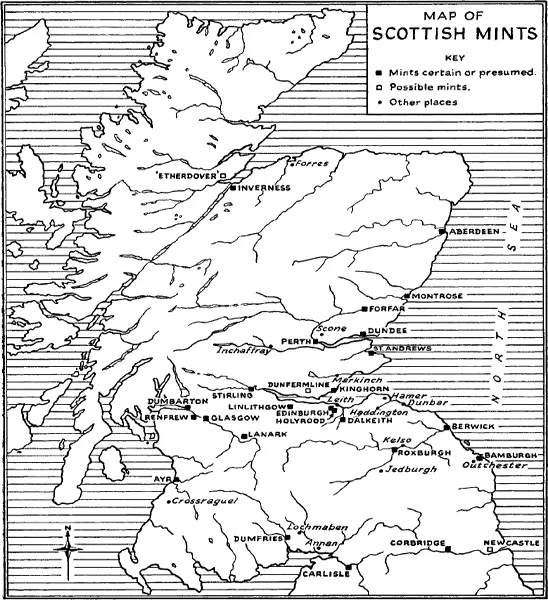

I wish to acknowledge the help I have received by way of specific comment on this paper in draft. Colonel and Mrs J. K. R. Murray and Mr Robert B. K. Stevenson have made extensive and valuable comment on all parts of it and I am as usual deeply indebted to them for their expert criticism. I have also discussed parts of this paper or its subject matter, to my great benefit, with Professor Geoffrey Barrow, Mr Christopher Blunt, Dr James Davidson, Professor Gordon Donaldson and Mr Philip Grierson, and with others whose names are mentioned in the following pages. Finally, I wish to thank Mr Peter Donald for drawing the map on p. 167.

I THE LOCATION AND FUNCTION OF MINTS1

Though all mints exist to produce coinage, their functions in a broader sense vary greatly. In all cases there must be a need for coin, a source of bullion and facilities for manufacture. The principal purposes of coinage are to maintain an adequate currency, to provide a means of payment for the expenditure of the issuing authority and as a source of revenue or taxation. Since there was often an abundance of foreign coin available, a native coinage of silver in the earlier period, and of gold perhaps usually, was also a matter of prestige.2 The activity and location of mints therefore depends on a mixture of commercial and political requirements. Scottish coinage offers unusually suitable material for observing the effects of such considerations. Medieval Scotland was sufficient of a state to support an independent and more or less continuous coinage, and as a kingdom it possessed enough unity for currency to be administered on a national rather than on a local basis. Yet it was a small and never very prosperous country, whose rarely extensive coinage can at most stages be encompassed by the modern student to the detail of individual dies.

Geographically, the distribution of mints in Scotland accords with the pattern of habitation which the physical features of the country impose upon it. The fertile midland valley, between Clyde and Forth, and the plain which continues up the eastern coast had long been inhabited; together with the Border lands down to the valley of Tweed and the Solway Firth, they have constituted the cultivated and more civilised areas of Scotland throughout her history. In contrast, the life of the highlands has always been confined to more or less isolated communities with little opportunity for cultural or economic advance.

In its earliest phase, Scottish coinage was concentrated in the Border lands, at first at mints in what is now England – Carlisle, Corbridge, Bamburgh – and thereafter mainly at the Scottish Border fortresses of Roxburgh and Berwick. Even Edinburgh played only a minor and occasional part in twelfth-century coinage, and the northernmost mint, Perth, was not enlisted except in an emergency. The most comprehensive pattern emerges with the Alexandrian recoinage of 1250, of which the mints were widely spread throughout the country. But even then the only mint northwest of a line from the Firth of Clyde to Aberdeen was Inverness, a strategic fortress often used by Scottish kings as a base for dealing with northern and highland affairs. But after 1300, in spite of occasional bouts of coinage at Aberdeen and Inverness, the proportion of Scottish coinage struck north of Perth was infinitesimal.

Many other of the places which had mints owed their importance to strategic positions. Stirling, in the heart of the midland valley, guarded the main route north and south, and many battles were fought for possession of its bridge over the Forth. North from Stirling, the bridge over the Tay at Perth opened up the lands of the eastern seaboard. Access by water enabled the English to hold both these strongholds in the midst of a hostile country. The rock of Edinburgh, close to the Forth, was a natural fortress, as was Dumbarton, centre of the ancient kingdom of Strathclyde. Berwick, bridging the Tweed, served alternately to facilitate the flow of trade with England and to resist her armies. The south, where several mints were situated, both prospered and suffered according to the state of Anglo-Scottish relations. There were more mint towns in the east than the southwest, for although Galloway is no more than twenty miles from Ireland, Scottish interests overseas looked to the Continent, politically to France, commercially to the Baltic and the Low Countries.

Because of changes in the effective Anglo-Scottish border, of invasion or of internal political considerations, some places at certain periods were not directly available to the crown or its representatives for coinage. The most extreme case of this was during the Wars of Independence; after Wallace’s capture and before Bruce’s recovery of the kingdom, Scottish coinage must be presumed to have ceased entirely since the urban centres were all in enemy hands. Several Border mints changed hands between the English and the Scots, Carlisle reverting to the Scots from 1136 to 1157, Roxburgh being held by the English from 1346 to 1460 and Berwick alternating more frequently: the first and last of these were used by either side when in possession. Coinage was also apparently in abeyance at Berwick and Edinburgh when William I surrendered their castles to Angevin garrisons, though it may have continued in the town of Roxburgh when its castle was occupied at the same period. Internal limitations also existed, for the king would normally coin only in his own burghs, and when they were available to him. Dumfries, for example, did not come into the hands of the king until 1186, and of Aberdeen and Inverness, both mints of the Albany regency in the early fifteenth century, the latter was occupied for a period in 1411 by the Lord of the Isles, and the former was threatened in the same year and on other occasions.

Within their locality, mints were no doubt situated with a view to security, amenity and facility. The dies for coinage, as well as the bullion, were precious, and the mint rooms or building had to be secure. This particularly applied in the case of the towns of Lothian and the Borders, which were open to attacks from the English; it is not surprising that a castle was often chosen to house the mint. On the other hand, the noise and heat of a minting workshop would have been highly disagreeable to the inhabitants of a castle if too close at hand, and it would usually be set apart from the living quarters, as at Stirling. Mints established for decentralised recoinage or commercial reasons would need to be conveniently situated for market or port. Always there had to be room for the plant and equipment involved in minting – furnaces, anvils, workbenches for cutting and weighing, storage for silver and dies – which was similar to that available to a jeweller, although on a larger scale, as well as provision for the administrative side of coinage – exchange, assay and record.3 The establishment of a mint therefore involved preparation and outlay, although on occasions it could apparently be improvised with speed as at the siege of Roxburgh; it was convenient if a previously existing mint could be revived, as no doubt happened in c. 1280 with some of the mints that had operated in the recoinage of 1250, and when mints such as Carlisle and Berwick changed hands their captors were not slow to convert to their own use the minting facilities which they had acquired. Quite apart from this, there was probably some element of precedent and tradition in the choice or retention of mints.

Little is known of the exact situation or physical nature of Scottish mints in the middle ages. There is no evidence that they ever existed as public buildings in their own right, such as the fourteenth-century hôtel de la monnaie which can still be seen at Figeac in Aquitaine where the Black Prince had a mint.4 Of those within castle walls, that at Stirling was in the gatehouse at the northeast entrance, before the Great Hall.5 Sometimes a mint was operated in a private house. Even the Edinburgh mint seems to have been so placed at certain periods, as the mint accounts explain. Five pounds were paid in 1358 for a year’s rent of a private house ‘pro monetario’; perhaps the regular mint had not yet been refitted for use after long abeyance, since the same account records that £9 10s. was spent ‘pro tectura et reparacione domorum monetariorum de mandato Regis’.6 There are also several references to houses containing the mint under James II. One apparently belonged to the king – £3 13s. 4d. was paid ‘pro annuo redditu hospitii domini Regis prope portam de Kirkstile . . . in quo hospitio dicta moneta fabricator’.7 Others belonged to private individuals: in 1441 one John Swift was paid £2 13s. 4d., ‘pro firma domus dicte cone’,8 and the same phrase is used of 6s. 8d. paid to Robert Hakate in 1443, in relation to coinage at Stirling.9 As late as 1581 coinage had to be carried out in a private house because the mint was in disrepair.

In the earliest period, when the names of individual moneyers appeared on the coins, what constituted a mint is even more obscure. Sometimes, if more than one moneyer at a time was operating in the same town as, say, at Berwick, Edinburgh or Roxburgh under Alexander ...