![]()

1

Introduction: the making of the region

The region

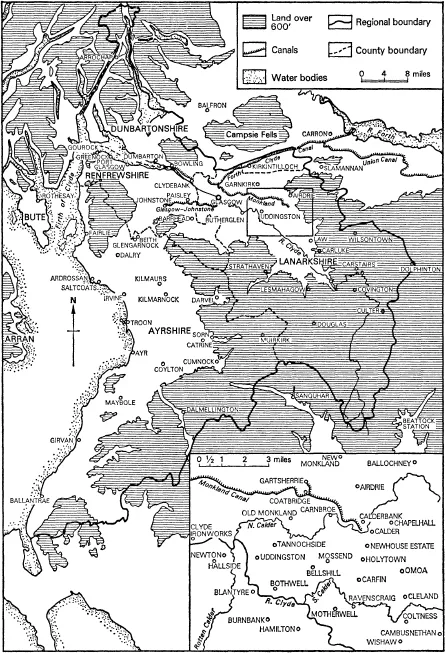

In the western half of the Scottish Lowlands a great triangle can be drawn to join Arrochar at the head of Loch Long, Dolphinton on the eastern rim of Lanarkshire, and Ballantrae on the south Ayrshire coast. Within it lies the region of the west of Scotland, nestling between the rugged masses of the Highlands and the Southern Uplands. The area is commonly called ‘lowland’ but barely half is under 600 feet (Map 1). The landscape is cluttered with hummocks of sands, clays and gravels left behind from the Ice Age, and cut by deep valleys formed by the biting incision of small and active streams. Their vigour gave the power for the initial industrial expansion in textiles, but in cutting into the earth they uncovered a successor. Coal seams were exposed on numerous valley sides, and the Clyde and Ayrshire lowlands were found to be underlain by Scotland’s richest coal and iron fields. The west of Scotland built its industrial success on these resources.

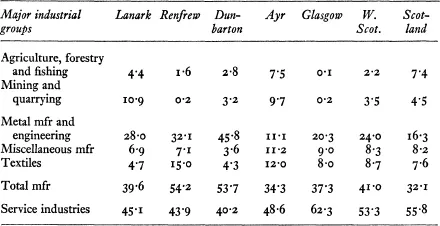

In the 1950s the west of Scotland was a mature industrial area, Scotland’s manufacturing region par excellence . Its initial prosperity had rested on textiles followed by metals, coal, heavy engineering and ships. These specialisations had persisted. In 1951 over 60 per cent of all manufacturing jobs in Scotland were in the west; in the metal-working group the proportion was over 70 per cent (Table 1). Glasgow, at the centre of the region, appeared to have a more diversified economy than the surrounding counties, 60 per cent of its jobs being in service trades. Yet this was deceptive. These activities were closely dependent on the prosperity of the staple industries in the region. When these faltered the Glasgow economy could not escape stagnation for long.

MAP 1 The west of Scotland: Location

TABLE 1 Percentage distribution of employment, 1951

West of Scotland share of total employment in each group (1951)

| Major industrial groups | % employment in

West of Scotland |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing | 14·5 |

| Mining and quarrying | 37·2 |

| Metal mfr and engineering | 70·7 |

| Miscellaneous mfr | 48·4 |

| Textiles | 55·0 |

| Total mfr | 61·3 |

| Services | 56·5 |

Source: Compiled from Census of Scotland, 1951

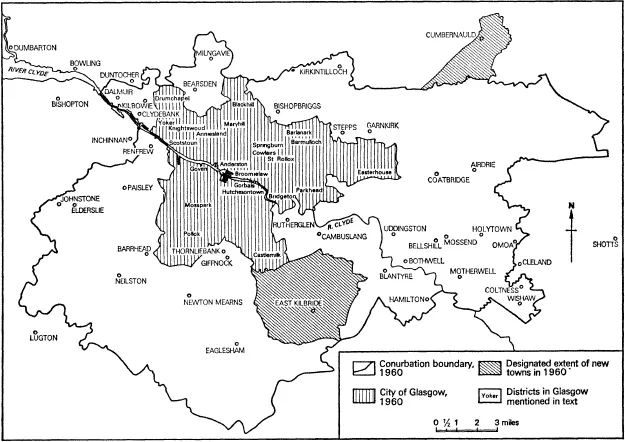

The west of Scotland is a small region, covering barely 2,500 square miles, about 8 per cent of the Scottish land area. Yet almost half Scotland’s population lived there in 1951, and one Scot in five dwelt within the 60 square-mile area of Glasgow. Ninety-five per cent of the region’s people were urban dwellers, most living within the complex and virtually continuous zone of built-up settlement known as the Central Clydeside conurbation (Map 2). One consequence was poor housing for many of the region’s inhabitants.

This complex urban-industrial society was a far cry from the west of Scotland of James Watt, Adam Smith or Robert Burns. Two centuries ago the west was an empty region with only seven people for every 100 living there in 1951; 181,000 inhabitants instead of 2·5 million. At that time over half the population lived in tiny hamlets with fewer than 300 persons; only one person in five lived in a settlement of 1,000 or more inhabitants. Glasgow had a population of only 23,544, Paisley 6,799, Greenock 3,858. Most other towns were much smaller.

MAP 2 Glasgow and Central Clydeside conurbation

This was a small-scale world where the wheeled vehicle was still uncommon. Few jobs were beyond the strength of man or animal power, and water served for the bigger tasks. Individual insecurity was common, expectation of life at birth being scarcely thirty years. The harvest was the single most important event of the year, for scarcity if not outright starvation was still common in this agrarian society. Some two-thirds of the population probably lived and worked on the land which lay derelict under the weight of ignorance and centuries of misuse.

In the middle of the eighteenth century it is impossible to identify a west of Scotland region, much less an integrated economy with dominant characteristics of the kind recognisable in the 1950s. Two hundred years ago there was a small colonial trade economy based on the infant Clyde ports. In the small towns and villages there was a linen textile economy; in the countryside itself, an agrarian economy struggling with unproductive land. No influence had yet emerged to weld these into a distinctive region. The gap between life in the region in the 1750s and the 1950s is remarkably wide, and in the 1750s there were few signs of the spectacular changes to come. Yet from these discouraging beginnings much was to be achieved in a very short space of time; the old society crumpled with remarkable speed.

The processes which transformed the pre-industrial region to its present form were linked to five broad and complementary upheavals. One major influence was the unprecedented population growth which turned the empty region into the congested area of the mid-twentieth century. A second was the series of improvements in transport which linked the region and its resources in productive ways. A third was the enormous expansion of foreign trade which drew the region into contact with world markets. The other two revolutionary changes embraced the reform of agriculture, and last, the crowning achievement of the age, the creation of machine-powered manufacturing industry. These great developments meshed with each other in a complex way and revolutionised the way of life of the region and its people.

The transformation was worked out over two centuries. In the first hundred years the west of Scotland climbed to world leadership in industrial strength while in the second century, from the decade 1870–80, the region slipped steadily out of the world limelight and became preoccupied with internal difficulties. The explanations of the upswing to prominence and the decline to relative insignificance are not simple. A brief outline of the pattern of change over the past 200 years will serve as a basis for the discussion to follow.

The first hundred years

Trade and the land

The west of Scotland moved from rural poverty to industrial prosperity in the century after 1760. The transformation of the countryside was a central part of this process, but rapid change was at first most evident in the striking growth of trade, especially the import and re-export of American tobacco.

This trade was still a small affair in the 1740s, with imports of around 10 million lbs of tobacco annually. But by 1770 imports had quadrupled and Glasgow controlled about half the entire British tobacco trade. Shorter sailing routes, superior credit facilities and commercial organisation, and regular outlets to the French tobacco monopoly carried the Scots to a position of pre-eminence. This had scarcely been attained before the trade was ruptured by the American War of Independence. Some bankruptcies ensued and trade faltered for a time, but commercial foresight permitted a steady switch of capital and enterprise into the trade with the West Indies. Sugar, molasses, rum and cotton replaced tobacco as the mainstays of foreign commerce.

The tobacco trade was short-lived, it was controlled by relatively few firms, and it was not closely linked to other activities in the region. Nevertheless, it strongly influenced two longer-term developments. Its scale threw great strains on the carrying capacity of the River Clyde and on local facilities for handling capital.

Between 1760 and 1800 the advice and work of Smeaton, Golborne and Rennie began the long conversion of the Clyde from unnavigable mudflats to a ship canal. At the same time the Forth and Clyde Canal was opened to stimulate east-west trade and provide Glasgow merchants with a water outlet to European markets. These improvements in communications met some of the immediate needs of the growing merchant community, but the supply of credit was more pressing still.

The tobacco trade poured liquid capital into the region, and some of the new trading elite placed their money in new banks; mercantile capital supported the small Ship, Arms and Thistle banks. But others were also involved. The security of landed property attracted loans to support a new life style, and landed wealth underwrote a number of the regional banks. After 1750 the interests and actions of merchants, landowners and bankers became intimately interwoven. The nouveaux riches edged into ownership of failing estates, bringing with them the discipline and expectations of business. This infusion helped break the inertia of custom and encouraged the move toward agricultural improvement.

In principle, the new agriculture involved basic changes in the organisation of the farmland, the introduction of new ways of working the land, together with new crops and livestock, and the use of improved implements. Scattered strips were consolidated in compact farms; land was levelled, drained and fertilised; new crop rotations and improved livestock capitalised on these innovations. This movement gained momentum from the 1760s, but its effects were not widely felt till the end of the century. Only then did growing urban demand combine with inflationary prices during the Napoleonic wars to transform the region’s agriculture. The new techniques loosened the harsh control of the physical environment and made possible an increase in output and productivity at a time when towns and industry were beginning to make unprecedented demands for more food and a new labour force. The key influence in the industrial developments was the emergence of the new cotton-textile industry.

Textiles

It was the dramatic impact of the textile industries which first gave a regional identity to the west of Scotland. From 1727 the Board of Trustees for Improving Fisheries and Manufactures employed modest funds and powerful persuasion in stimulating economic activity. In particular the linen industry responded to careful attention to the quality of flax, and improvements in spinning and finishing. In the west of Scotland emphasis was placed on quality and skill, and the domestic industry was gradually taken over by town-based yarn merchants. These men provided credit and yarn, and linked town and countryside as never before. Between 1748 and 1778 the region’s output more than doubled to 3·3 million yards of cloth, the value increasing from one-third to 40 per cent of the Scottish total. A decade later this had declined to 15 per cent by value, although the region’s output remained the same. After 1780 the east-coast industry strode ahead as linen merchants in the west found their attention drawn to a new product.

Cotton was the new star on the horizon, and the English had already demonstrated what could be done with the simple mechanical inventions of the spinning jenny, water-frame and mule. Its sudden and dramatic growth transformed the economic base of the west of Scotland and separated the old generation, who looked back to the land as the normal way of life, from the new one whose members became the first real urban dwellers in the modern sense of the term. Even so, the old and new ways of life were not yet completely divorced. The first spinning mills were sited in the countryside and supported many out-workers in spinning and weaving. Textile workers could still live and work in the countryside, even though the first step toward the appearance of the factory wage-earner had been taken.

The next step attracted mills to the towns and widened the gulf between the old and new societies. This came after 1800 as steam power contributed its regular untiring motion to driving textile machinery. The urban mill was dominant by 1830, though the illusion of a link to the old way of life and work in the countryside was maintained by the rural mills. This was strengthened by the lack of refinement of the early power looms which permitted growing numbers of hand-loom weavers to maintain some independence and avoid total absorption into the new factory system. Immigrant Irish and Highlanders joined their ranks, as well as entering the spinning mills. Their swelling numbers finally solved the labour-supply problem, since previously the new mills could not readily attract the literate lowland Scot. Indeed, the new factory labour force and the new urban society in the west of Scotland rested upon the illiterate, the hungry, the dispossessed and the immigrant. The western towns were the harsh frontier for the decaying peasant and expanding industrial societies.

This new urban frontier had grown substantially by 1830. Glasgow alone was a city of over 200,000, housing nearly one-third of the region’s 628,000 people; almost two-thirds of these were already urban dwellers. Between 1755 and 1831 the region’s population grew three-and-a-half fold. Natural increase, the decanting of surplus rural dwellers, and the influx of Irish and Highlanders combined to create the fabric of the west of Scotland’s urban life in these years. With so many of the incomers lacking skill and education, they added their minimal social standards to the unpreparedness of town authorities. Together, these produced the roots of squalor and slumdom which have typified Scottish industrial communities.

These momentous changes were intermixed with an astonishing improvement in communications. The canals attracted much contemporary attention, but, placed in perspective, they played a relatively small and specialised part in the economic and social transformation of the region. The new developments were supported by a more prosaic, but more widespread, improvement in roads. In spite of the deepening of the Clyde and cutting of the canals, the urban and rural cotton mills were heavily dependent on road transport. Similarly, the early ironworks at Muirkirk, Wilsontown and Clyde all relied on roads. Moreover, the revolution in the countryside, which enabled people and food to flow to the towns, was equally dependent on the building of a dense network of roads and bridges.

By 1830 these changes, which made up the first stage of the industrial revolution, had begun to weave the parochial world of the west of Scotland into a recognisable economic unit. In the countryside the new commercial farming catered for the local urban markets: in the towns and villages a thriving textile industry rivalled the prestige if not the scale of cotton in Lancashire: on the Clyde, the coast-wise trade was being bound together by the most extensive system of steamship services anywhere in Britain or Europe. The west of Scotland had evolved a base from which a broad thrust into industrialisation could be sustained in the decades from 1830 to 1870.

Coal and iron

In England the momentum in industrialisation had been carried forward on the two prongs of the new technology in cotton and the revolution in the production of iron following Darby’s use of coke instead of charcoal in the furnace, and Henry Cort’s processes of puddling and rolling to remove impurities and convert crude pig-iron to the more valuable bar- or wrought-iron. Scotland has successfully borrowed the new technology in cotton production but the iron revolution was not transferred so easily. Production was constrained because of poor-quality coking coals and phosphoric iron ores which produced a weak and brittle, yet high-cost, pig-iron from the small furnaces. Ten ironworks were established between 1759 and 1801, seven of them in the region; but total output was only 22,800 tons in 1806, and still only 29,000 tons in 1825.

The great innovation which freed Scottish ironmakers from high-cost, low-quality production was the introduction by James Neilson of his hot-blast technique between 1828 and 1832. This raised the temperature of the small and inefficient furnaces and made an acceptable pig-iron from local ironstone, the black-band, coal-measure iron ores discovered by David Mushet in 1801. When raw splint coal was substituted for coke this, together with other refinements, cut coal consumption in local furnaces by up to two-thirds, increased the yield, and gave Scottish ironmasters an immediate and major cost advantage over English and Welsh producers. These were the first uniquely Scottish contributions to the processes of the industrial revolution and the consequence was a prodigious Scottish investment in ironworks and coal mines, for the major ironmakers were also the main coal masters.

The transformation was dramatic. Iron output leapt from 29,000 tons in 1829 to 240,000 in 1840, and over 1 million tons by 1870. The region’s coal production swept upward too, from perhaps 650,000–750,000 tons in 1800 to about 5 million in 1854. By 1870, 11 million of Scotland’s 15 million tons were produced in the west. This prodigious expansion shifted the focus of industrial growt...