- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Did British Capitalism Breed Inequality?

About this book

First Published in 2005. This thirteen-chapter title is divided into three parts and concludes with five appendices, references, and index. The first part focuses on income inequality and the historical state of wages. The second begins the discussion on the driving forces of economic inequality and equilibrating factors. The third provides a model for inequality in a resource-scarce open economy with data, theory, and debate. Appropriate for economic students and those interested in British economic history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Did British Capitalism Breed Inequality? by Jeffrey G. Williamson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Issues

Did British capitalism breed inequality? Opinion has always been in ready supply. The debate still rages in the academic literature; it creeps into most contemporary public debates over taxes, government spending and regulation; and it colors our view of inequality trends that we believe Third World countries should anticipate. This is perhaps because, for the classic British case, the participants in the debate have rarely gathered hard evidence to document inequality trends before World War I. One can sympathize, since few hard data were available then and the distant past offers only indirect clues now. We have the occasional parliamentary income tax and estate tax returns for the nineteenth century used by Marx, Porter and others in the Victorian debate. Around the turn of the century, Arthur Bowley and his colleagues added their impressive compilation of nineteenth-century wages. Beyond these, we have only the rare guesses at the national income distribution by King, Massie, Colquhoun, Baxter and Bowley, limited estimates of the distribution of earnings among ‘manual workers’, and street-level impressions of the sort that Friedrich Engels used to heat up the debate in the 1840s.

After a two-year visit to England, Engels fired the first public salvo. His first major work deplored the condition of the working class in no uncertain terms, and apologists for capitalism have been on the defensive ever since. Before-the industrial revolution, Engels (1974, p. 10) tells us,

The workers enjoyed a comfortable and peaceful existence. They were righteous, God-fearing and honest. Their standard of life was much better than that of the factory worker today. They were not forced to work excessive hours; they themselves fixed the length of their working day and still earned enough for their needs . . . Most of them were strong, well-built people, whose physique was virtually equal to that of neighbouring agricultural workers. Children grew up in the open air of the countryside, and if they were old enough to help their parents work, this was only an occasional employment and there was no question of an eight- or twelve-hour day.

Three years later, The Communist Manifesto (Marx and Engels, 1930, pp. 34–6) added the final touches to the classic description of middle- and lower-class impoverishment in the midst of accelerating economy-wide productivity growth:

Owing to the ever more extended use of machinery and the division of labour, the work of these proletarians has completely lost its individual character and therefore forfeited all its charm for the workers. The worker has become a mere appendage to a machine . . . [Wages] decrease in proportion as the repulsiveness of the labour increases . . . Those who have hitherto belonged to the lower middle class – small manufacturers, small traders, minor recipients of unearned income, handicraftsmen, and peasants – slip down, one and all, into the proletariat. . . Private property has been abolished for nine-tenths of the population; it exists only because these nine-tenths have none of it.

Two decades later, these opinions became a ‘General Law of Capitalist Accumulation’ in Marx’s Capital (1947, vol. I, pp. 659–60):

The greater the social wealth, the functioning capital, the extent and energy of its growth . . . the greater is the industrial reserve army . . . and the greater is official pauperism. This is the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation.

Like Engels, Marx asserted that the lot of the workers had grown worse, although it can be argued that both had relative ‘immiseration’ in mind rather than absolute impoverishment.

Engels and Marx were hardly alone in stating publicly that inequality was on the rise in England. Speaking to the House of Commons in 1911, Philip Snowden paraphrased Marx with a statement that has now become part of our common lexicon (cited in Whitaker, 1914, p. 44): ‘The working people are getting poorer. The rich are getting richer . . . They are getting enormously rich. They are getting shamefully rich. They are getting dangerously rich.’

Anyone can play the polemic game, and apologists for capitalism rose to the challenge. Porter (1851) and Giffen (1889) countered the radical critique by using limited nineteenth-century tax return data to suggest an egalitarian trend, and the editor of the Economist, F. W. Hirst (cited in Whitaker, 1914, p. 44), said it was still true in 1912. With equally slim evidence, Alfred Marshall (1910, p. 687) added his weighty influence to the optimistic camp:

It is doubtful whether the aggregate of the riches of the very rich are as large a part of national wealth ... in England, now as they have been in some earlier phases of civilization . . . The returns of the income tax and the house tax, the statistics of consumption of commodities, the records of salaries paid to the higher and the lower ranks of servants of Government and public companies . . . indicate that middle-class incomes are increasing faster than those of the rich; that earnings of artisans are increasing faster than those of professional classes, and that the wages of healthy and vigorous unskilled labourers are increasing faster even than those of the average artisan.

Common to each camp in the debate, of course, is the tendency to denigrate the other’s ‘evidence’. Thus Eric Hobsbawm (1964, p. 293) counsels us to

dismiss Marshall since his ‘observations on the subject. . . are exceptionally unreliable (or perhaps wishful)’. The apologists have been equally unkind towards the radicals’ use of ‘evidence’, Hobsbawm included (Hughes, n.d.; Lindert and Williamson, 1983a).

Documenting past inequality trends in Britain seems to be long overdue. Although better and more evidence is unlikely to end the debate, it certainly can help make it better informed. Part I of this book is devoted to that end. Chapter 2 offers new evidence on the standard of living from the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Chapter 3 reconstructs earnings distributions between 1827 and 1901, and documents trends in the structure of pay by skill for even longer periods, starting with the 1780s. Chapter 4 collects what is known about income inequality, including the views of the ‘social arithmeticians’ from Gregory King to Arthur Bowley. As it turns out, the evidence in Part I seems to trace out what has come to be known as the Kuznets curve (Kuznets, 1955) – inequality rising sharply up to somewhere in the middle of the nineteenth century and falling modestly thereafter.

Part II of the book theorizes about potential explanations of the British Kuznets curve. Factor markets are the key, with labor markets playing the central role. Once we understand the impact of changing demographic, technological and world trade conditions on factor rewards in those markets, we understand much about the forces driving the Kuznets curve from 1760 to World War I. Part II suggests how helpful it is to distinguish disequilib- rating factor demand forces, which tend to augment inequality during early industrialization, from equilibrating factor supply responses, which tend to produce egalitarian trends during late industrialization. The distinction is especially helpful in organizing the debate between the critics of and apologists for capitalism.

The dialogue between the critics and defenders of capitalism has been going on now for at least 150 years since the British reform debates started to heat up in the 1830s. Furthermore, there is no evidence that the exchange has cooled down, since the same intensity characterizes debate over rising inequality in Latin America and elsewhere in the industrializing Third World today. What appears in Part III is largely motivated by those debates. Thus, the remainder of the book is devoted to developing a model of the British economy that is capable of saying something about growth, industrialization, the standard of living and inequality. The model is developed in Chapter 8 and tested in Chapter 9. It is then used in Chapter 10 to uncover the sources of the British Kuznets curve during Pax Britannica, that is from 1821 to 1911. The final step is to explain why British growth was so slow before the 1820s (Chapter 11). Once we understand the impact that the wars had on the British economy, then the sources of the dismal standard-of-living performance up to the 1820s become clearer (Chapter 12). Some peculiar attributes of British inequality trends between the 1780s and the 1820s also become clearer.

We are now equipped to confront three questions motivating this book. Did British capitalism breed inequality? Why? Could Britain have avoided it?

PART I

2

Real Wages and the Standard of Living

(1) The debate

Did real wages rise during the industrial revolution? Who gained from capitalist growth?

The dominant view in the nineteenth century was that common labor gained little during the early years of the industrial revolution. Apologists for British capitalism could concede that real wages failed to improve up to mid-century, while they basked in the abundant evidence of workers’ prosperity in the late Victorian era. Capitalism may have had an awkward youth, but it looked good in middle age.

The debate over the standard of living during the industrial revolution1 heated up again in the 1920s with the appearance of J. H. Clapham’s An Economic History of Modem Britain (1926). Clapham’s contribution was to introduce quantification where anecdotal evidence had served before. On the basis of the work of Bowley, Wood and Silberling, Clapham estimated that real wages of the ‘average’ industrial worker rose by 60 per cent between 1790 and 1850 (Clapham, 1926, pp. 128 and 561). For every optimist there is a pessimist, and in this case it was J. L. Hammond (1930) who led the counterattack. Hammond conceded the optimists’ evidence of real wage improvement up to 1850, but argued that more food and better clothing were poor substitutes for the quality of life that capitalism’s ‘dark satanic mills’ destroyed. While T. S. Ashton (1949) carried the apologists’ torch in the interim, the intensity of the modern debate diminished until the appearance of the more recent exchange between Max Hartwell (1959, 1961) and Eric Hobsbawm (1957). Hobsbawm, the pessimist, argued that Hammond gave up far too much ground to Clapham and that the quality of life and material standards both deteriorated. Hartwell, the optimist, introduced more economic theory into the debate while shifting the attack towards inequality issues – towards relative performance as opposed to absolutes.

The timing of the Hartwell–Hobsbawm exchange should occasion no surprise, for it was in the late 1950s that social scientists began to confront the problem of Third World industrialization, turning for guidance to historical evidence from the early industrializers. Furthermore, it was the pessimists’ view that dominated expectations, and the models that development economists brought to Third World experience reflected that view. This was the heyday of W. Arthur Lewis’ (1954) model of ‘labour surplus’, brought to a formal head by John Fei and Gustav Ranis (1964), a position now embedded in models of growth and development. The ‘stylized fact’ of stable real wages during early industrialization was the pessimists’ ultimate intellectual contribution.

Is this ‘stylized fact’ warranted? As we shall see in this chapter, it certainly is not: after the pronounced effects of the French Wars had subsided, real wages of common labor rose rapidly from 1820 to 1850. Nevertheless, there remains the important question of whose wages grew fastest. Indeed, that we care in this book at all about real wages implies that the distribution of income is linked closely with the fortunes of the common laborer. So it is that this chapter will also serve to introduce the wage inequality issues that will take so much time in Chapter 3.

(2) Who were the workers?

Which occupations and social classes are of the greatest relevance to the debate? The participants are unlikely ever fully to agree, but a few groups have been of prime concern to both camps in the British nineteenth century debates and in contemporary Third World debates.

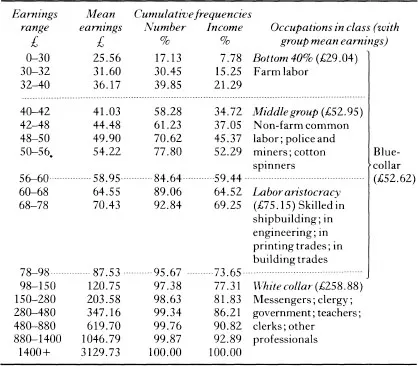

Following established conventions in the literature, each group listed in Tables 2.1–2.3 refers to adult male employees; self-employed females, children and chronic paupers are all excluded. The lowest class is dominated by hired farm laborers, a large group of workers who represented the bottom 40 per cent of the earnings distribution in the early nineteenth century,2 at least among active participants in the labor force. (Paupers are another matter, discussed at length below.) Next come common laborers and miners, their near-substitutes, a ‘middle group’ dominated by urban occupations requiring little skill. Hobsbawm’s (1964) ‘labor aristocracy comes next, a group falling roughly between the 60th and 80th percentiles in the overall distribution of earnings. The ‘aristocracy’ includes the following artisans: fitters, turners, iron-molders, shipwrights, compositors, bricklayers, masons, carpenters and plasterers. Blue-collar workers comprise all of these listed thus far, a definition that fits ‘the working class’ most closely.3 The list is completed by the addition of a diverse white-collar class: messengers, porters, police, teachers, doctors, barristers, clergymen, engineers and many others.

While these class rankings changed very little in the early nineteenth century, they certainly enjoyed very different real earnings growth between 1827 and 1851. Earnings of the bottom 40 per cent declined from 49 to 38 per cent of the average, and blue-collar workers’ pay fell from 82 to 70 per cent. The white-collar aristocracy, on the other hand, improved their position from 227 to 343 per cent of the average. These trends reflect a ‘stretching’ in the wage structure and a rise in earnings inequality that, as it turns out, (Chapter 3), was most pronounced during these three decades.

Table 2.1 1851 estimated earnings distribution for England and Wales: occupations classified by earnings class

Sources and Notes: See Table 2.1.

These movements in relative earnings between 1827 and 1851 serve to illustrate the importance of examining the wage experience of various laboring classes. Growth was cert...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Issues

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Appendices

- References

- Index