- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 2005. This title studies the 1981 insurrection of the Spanish 'Guardia Civil', motivated by political and economic factors. The politico-economic causes of the February incident have been succinctly summarized and traced the institutional causality which explains the peculiarities of contemporary Spanish development. Within are chapters on Spanish agriculture, policies, the industrial revolution, and the economic crisis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Contemporary Spanish Economy by Sima lieberman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

Contemporary Spanish Agriculture in Historical Perspective

Traditional Agriculture in Spain

Looking at the aggregate economic performance of the Spanish economy in the 1960s, it is no exaggeration to label the period extending from 1960 to 1972 as the decade of a W. W. Rostow-like ‘industrial take-off’. During this period, Spain’s real gross national product grew at an annual average rate of 7.3 %, a rate of growth which allowed a doubling of per capita income between 1965 and 1972 and which elevated the relative position of Spain’s per capita income from about half that of Western Europe in the early 1960sabout US$500 for Spain as compared with US$1, 000 for Western Europe – to between two-thirds and three-fourths of the Western European average at the end of the decade – US$1, 300 for Spain and US$1, 800 for Western Europe. The rates of economic growth achieved by the Spanish economy in the 1960s not only exceeded those recorded during any earlier period of Spain’s economic history, but also figured among the highest rates of economic growth realized during the 1960s in Western Europe and in the world. The Spanish Stabilization Plan of 1959 indeed announced the coming of an impressive ‘economic miracle’. Per capita income in Spain in 1958 was still lower than it had been in 1930, but by 1970 this per capita income exceeded corresponding income levels in Eastern Europe, in Mediterranean Europe, with the exception of Italy, and in most of Latin America. The 1960s brought rapid industrialization, urbanization and significant rural emigration to Spain, phenomena which resulted in a major transformation of the economy, and Spain ceased to be an essentially agrarian country.

Not all of the sectors of the economy responded adequately to the needs of economic transformation and modernization. Spain’s agricultural sector maintained during this period strong institutional rigidities which inhibited and retarded necessary technological and organizational changes. Vested interests were still able to have the government support traditional systems of land tenure and of agricultural production. Agricultural supply failed to adjust adequately to changes in agricultural demand. The relatively weak performance of the agricultural sector in the period 1962 to 1971 is clearly shown by intersectoral rates of expansion for this period; while the industrial sector expanded at an average annual rate of 8.5 % in terms of constant prices and the services sector grew at an annual rate of 6.7% in the same period, the average annual rate of growth of the agricultural sector was only 2.2%.

While the state and foreign firms were very active in the 1960s in developing and in modernizing the industrial sector, the system of land tenure and the methods of agricultural production in Spain remained subject to the immutability of centuries-old institutions, institutions whose roots go back to the times of the Reconquista and of the Catholic kings. The former brought the large landholding to Spain; the latter strengthened the feudal economic privileges of the large landowners and provided them over the duration of five centuries with an abundant supply of cheap labor. The crusades against the Moslem Moors in the long period stretching from the eighth to the fifteenth century gave a rigid and unchanging long– term pattern to the Spanish land tenure institutions. The reconquest of Moslem lands allowed a small number of landed magnates to live a life of leisure in urban centers, their estates being worked by masses of landless rural workers and of impoverished owners of minifundia. Spain’s agrarian structure received from the Reconquista the stamp of economic dualism; lands in northern and parts of central Spain were divided into minute and fragmented peasant holdings, while large tracts of land in Andalusia, Extremadura and La Mancha were granted by the Crown to the high nobility and to military and religious orders as compensation for services rendered during the wars of reconquest (Lacarra, 1951). Professor E. E. Malefakis has observed that ‘the early monopolization of property by the nobility and the Church was also reflected in the rural class structure of southern Spain. The earliest census that addressed itself to this question, the census of 1797, revealed a distribution of rural classes remarkably similar to that which exists today’.1 Indeed, the Agrarian Census of 1972 reveals that 1.2% of all Spanish landownership units covered an area representing nearly half of the total productive land area (Censo, 1975, p. 26).

The fact that a very small minority of Spanish landowners possessed the lion’s share of all productive land does not mean per se that this system of land tenure is economically inefficient. However, when we consider, along with this fact, a number of other aspects of the Spanish agricultural sector, it becomes evident that the survival of the latifundio has too often remained associated with public agricultural policies formulated to protect above all the interests of the large landowners, many of them absentee owners who showed no significant interest in abandoning traditional methods of production (Ibid., p. 26). The survival of the latifundio was accompanied by the survival of Spain’s ‘traditional agriculture’.

Let us briefly examine the main characteristics of this ‘traditional agriculture’. Historically, and including the first half of this century, the composition of the domestic agricultural supply satisfied a domestic demand for agricultural products that was typically the demand of a poor, underdeveloped country. The diet of the average Spaniard was very poor in animal protein. As late as the 1950s, Spanish consumption of animal protein ranked below that of Greece and Portugal. For centuries the typical Spanish diet had been based on cereals, leguminous vegetables, olive oil and wine. These products were offered by both latifundia and minifundia. The tight correspondence between the supply and the demand for these foodstuffs maintained through time the equilibrium and the continuity of the country’s traditional agriculture. Almost until the present day, large and small landowners have continued to give emphasis to the production of the traditional crops, partly because of the strength of tradition, especially for poorly educated peasants, and partly because the government’s price support policies encouraged the continuation of traditional production. As late as the 1950s, 60 % of all cultivated land in Spain was devoted to the production of cereals. This figure was still as high as 47.696 in 1972 (Ibid., p. 35).

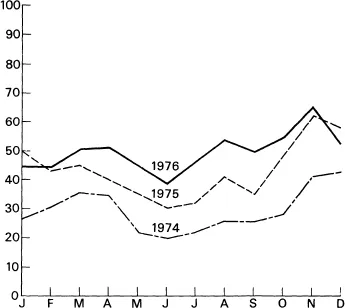

Spain’s traditional agriculture was also characterized by a surplus of poor, uneducated rural workers. In 1950, 48.8% of the total active population was agrarian. Although this percentage figure declined to 41.3% in 1960, to 29.3% in 1970 and to 21.5% in 1975, rural unemployment in 1975 amounted to about 42, 900 persons and rose to 48, 900 in 1976 (Ministerio de Agricultura, 1977, pp. 23–4). These figures indicate that Spain in the 1950s was still an essentially agrarian nation; although rapid industrialization and emigration in the 1960s brought a sharp reduction of the rural population, the agricultural sector continued to show large numbers of unemployed and underemployed, a typical characteristic of a still largely agrarian, developing economy. The continuing existence of a rural labor surplus tended to maintain the traditional economy. This surplus resulted directly from the traditional land tenure system based on the coexistence of minifundia and latifundia. The agricultural history of Spain has witnessed for centuries the seasonal migration from north to south of masses of poor small landowners, tenants and sharecroppers, not to speak of masses of miserable landless rural workers, in search of employment on the large southern estates. In the latifundio areas of southern Spain, these migrant workers had to compete with a large population of landless rural workers, these people representing over 50% of the southern active rural population.2 Whoever has traveled through the towns of southern Spain in the 1950s or the 1960s will remember the many manifestations of underemployment and unemployment. Among the typical sights so often photographed by the tourist was that of the water vendor, selling water by the swallow from his botijo, an earthen jug worth 300 pesetas which constituted the man’s entire capital; there were the many young and old men and women standing on bullfight days near the entrance to the Plaza de Toros, trying their best to sell cigarettes, sweets and cheap souvenirs; numberless boys and able-bodied men trying to survive by polishing shoes in the bars and the barber shops; their number was perhaps just matched by the loud vendors of ‘lucky’ lottery tickets. A sadder picture was that of the many day laborers, stoically waiting in the village square for a new amo, a new master who would offer them temporary employment in a vineyard, on a wheat field or on a construction site. The administrador of a large estate could hire gipsy workers by the day for a few pesetas, a tortilla and a glass of wine. One could not seriously speak of a capitalist, rural wage system in Spain. Feudalism had not left the Spanish countryside.

Rural underemployment and unemployment were tightly linked to the irregular, tradition-determined activities of Spanish agriculture, activities that remained highly dependent on climatological factors, to the absence of employment alternatives and to rapid population growth, particularly in southern Spain.3 It was only in the 1960s that the agricultural population started registering a sharp decline in numbers. The active agrarian population counted 4.5 million people in 1900. This population increased to 4.8 million in 1940, to 5.2 million in 1950 and declined to 4.7 million in 1960. In absolute numbers, the active agrarian population was larger in 1960 than it had been in 1900. It fell, however, to 2.9 million by 1970 (Ministerio de Economía, 1977, p. 51).

The abundance of cheap rural labor tended to discourage the introduction of more mechanized methods of production on the large estates, and inhibited capital accumulation by small farmers. The absence of technological advance in the rural sector maintained an Eckaus-type unemployment equilibrium (Eckaus, 1955). R. S. Eckaus has shown that the most labor-intensive agricultural methods of production require some minimum amount of capital per unit of labor; production requires a minimum fixed ratio of capital to labor and if an economy does not possess sufficient capital to employ its entire rural labor force unemployment, or disguised unemployment, will naturally follow. If for some reason the surplus rural population cannot leave the agricultural sector, only capital accumulation in that sector will permit a drop in rural unemployment. The evidence supports the thesis that the Eckaus argument describes very well Spanish agricultural conditions, at least until 1960. With a low capital-labor ratio in 1960 of 2/3, a low mechanization index showing 350 hectares per tractor in the same year, a limited use of fertilizers – 26.4 kg/hectare for Spain as compared to 64.2 kg/hectare for the OECD countries – and with 58% of all dry-farming lands failing to receive any chemical fertilizers, Spain’s agriculture was indeed characterized by fixed factor proportions (García Delgado and Roldán López, 1974, pp. 73–104).

Government price support policies have also contributed much to the survival of traditional agriculture. These policies, especially those of the 1940s and the 1950s, purported to protect the small landowner and to render Spain self-sufficient in basic foodstuffs; in reality, they protected the prices of traditional crops to the prejudice of agricultural transformation. A public agency, the Servicio Nacional del Trigo, was established in 1937 in order to guarantee Spanish wheat producers adequate prices for their crop, regardless of market conditions. The SNT also provided these producers with fertilizers and extended to them short-term credits and subsidies. A direct result of the policies pursued by the SNT was an expansion of the output of wheat in the decade 1940 to 1950; this increase was due to an extension of the wheat area rather than to better yields. Spanish wheat yields remained half of those of France, and ranked well below those of England, Italy and Poland. New lands brought under wheat cultivation could have been used more advantageously in the production of fodder crops, which would have allowed an increase in the numbers of meat producing animáis. The deliberate disparity maintained by the government between the high price of wheat and relatively low guaranteed prices for fodder cereals impeded the necessary growth of cattle and hog raising. In the same way, the subsidization of certain industrial crops like cotton and beets, generally grown on large estates, operated to the detriment of an increase in the production of forage crops, limiting thereby increases in meat production. These policies benefited mostly the large estates, discouraged demand-dictated production changes on these, did little to reduce the large rural labor surpluses and hindered the development of a more varied and more demand-oriented agriculture. In addition, government measures designed to suppress the birth of any reformist movement gave further artificial stability to the traditional agricultural system. During the 1940s and the 1950s traditional agriculture seemed to remain anchored to a high degree of stability, marked by very slow structural and technological change, a stability that did not preclude the multiplication of economic and social problems – problems which had a direct impact on the whole economy.4

Figure 1.1 Estimated rural unemployment (in thousands of persons).

Source: Ministerio de Agricultura, La Agricultura Éspañola en 1976 (1977), p. 24.

Source: Ministerio de Agricultura, La Agricultura Éspañola en 1976 (1977), p. 24.

The Continuity of Feudal Institutions and the Land Tenure System

The continuity of land tenure systems in Spain must be understood in the light of historical perspective. Feudal institutions which crystallized in the thirteenth century did not disappear in later times and remained the strong pillars supporting traditional agriculture. While neo-feudal practices crumbled in Western Europe in the modern, capitalist period, they remained strong in Spain, probably because Spain never developed a fully capitalist system in the last five centuries.

The reconquest of Hispano-Moslem lands was not started by the devout Catholic inhabitants of Galicia, nor by the rugged peasants of the Cantabrian mountains. It was only during the middle of the ninth century that the Asturian ruler Ordoño I succeeded in occupying Astorga and León. Successful campaigns against the Hispano-Moslems had been started much earlier by Carolingian Franks, who, after crossing the Pyrenees, were victorious in a series of battles fought between 785 and 811, battles which allowed the establishment of a Spanish March which was to be part of the Carolingian empire. Frankish military and cultural influence had a major impact on the social and economic development of the eastern and central Pyrenean counties of Urgel, Pallars, Barcelona, Ribagorza, Sobrarbe and Aragón. Feudalism took roots in ninth century Spain, not in the kingdom of Asturias-León, but in the areas captured by the Carolingian Franks. The Franks not only brought with them the Carolingian script and the Franco-Roman religious rite, which soon replaced the Visigothic script and the HispanoVisigothic rite, but they also introduced the feudal concept that land should be distributed in exchange for military service. Briefly, the income of land should go to those who could defend it and land would be worked by those who could not defend it. It is not by accident that the word ‘fief appears in Catalonia only in the ninth century. When in the course of the late ninth century Frankish power waned in Catalonia, the strong feudal landholding system they had introduced survived. Catalonia was to be ruled for two centuries by a number of counts and local overlords who were only too eager to increase the burden of personal obligations imposed on their peasants. The recognition of seigneurial privileges was extended to newly conquered lands in the early eleventh century.

Social life in the Pyrenean non-Moslem valleys before the arrival of the Franks had been quite different. Although each valley had a local ruler known as the count, protected by a group of fideles, the peasantry governed by this count was both free and bonded. The ingenuili were free peasants; other peasants were simple serfs. The new Frankish system divided the population into two groups: one group cultivated the land while the other group, the ‘barons’, defended it. The leader of the warrior group was still the count; he was able to request military aid from his vassals, the comitores and valvasores, and their knights, the milites. Some peasants were able to remain free, but the majority became serfs or remenças who could buy their freedom; captured Moslems became slaves (Vicéns Vives, 1969, pp. 138–42).

The basis of the landholding system was the freehold or allodium, a unit or units of property acquired by individuals or monasteries with the consent of the emperor or that of the count. Under the practice of aprisio, land was acquired under royal permission and the grantee acquired hereditary rights over it. Grants under aprisio were also extended by the counts to their followers, to monasteries and to individuals. Topography made the acquisition of latifundia difficult, but large landed proprietors acquired large parcels of land scattered over wide areas.

During the eighth century, the south-central areas of the Pyrenees were organized as the counties of Aragón, Sobrarbe and Ribagorza. The area was poor and rugged and was inhabited mostly by shepherds and farmers. Peasants often accepted the protection of a military leader, the señor, fulfilling various obligations to their señor in exchange for the protection granted. An aristocratic class slowly developed, being initially constituted by poor military and administrative officials. The first kings of Aragón limited the privileges of these aristocrats and there were few hereditary fiefs. The power of the aristocracy increased however during the twelfth century; following the death of Alfonso I of Aragón and Navar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Institutions and Economic Development: The Spanish Case

- Chapter I Contemporary Spanish Agriculture in Historical Perspective

- Chapter II Agricultural PolicySince 1939

- Chapter III The Long Road to Spain’s Industrial Revolution

- Chapter IV The Spanish Industrial Revolution of the 1960s

- Chapter V The Economic Crisis of the 1970s

- Chapter VI The Restoration of Free Trade Unions, Unemployment and Future Growth

- Chapter VII Quo Vadis, Hispania?

- Bibliography

- Index