![]()

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

The object of this study is threefold. First, to examine the form and impact of British fiscal policy in the 1930s. Secondly, to investigate the theoretical, political and bureaucratic determinants of that policy. And thirdly, to assess the degree to which official economic thinking – supposedly enshrined in the infamous ‘Treasury view’ – had come to accept Keynesian prescriptions for deficient demand and mass unemployment by the eve of the Second World War.

The book thus focuses upon the origins of modern economic management in Britain. Whilst this subject continues to be much debated by economists and economic historians, as yet no real consensus exists, particularly on the issue of Keynes’s influence upon the Treasury. Throughout, the book is addressed to this and related questions. It seeks to lay bare the misconceptions of earlier works in order to advance our understanding of the 1930s fiscal policy debate. But it also has a broader purpose: to demonstrate to readers concerned with the current policy debate, as well as that of the 1930s, that changes in official economic thinking rarely derive from theoretical considerations, though clearly they are informed by them. Thus the 1930s policy debate should be of interest to those who have long harboured the suspicion that policy prescriptions which – at the theoretical level – appear to transcend reason almost invariably have political and bureaucratic foundations sufficiently powerful to ensure their continuance even in face of a sustained theoretical attack.

* * *

The achievement of full employment since the war (to, say, 1970) has generally been attributed – Matthews (1968) is here the one, prescient exception – to the success of Keynesian demand management, this appearing to vindicate the case for fiscal expansion put by Keynes and others between the wars. It is a major contention of this book that the Keynesian condemnation of interwar policy-makers has been both misdirected and myopically over-confident. As the interwar economic historiography developed there was absent any appreciation that the period was increasingly being viewed through the filter of the practical success of demand management since the war, and that the effect of this filter was not only to blur our image of the interwar period but also to generate an undue optimism about the permanence of the gains effected by the Keynesian revolution. For example, as recently as the early 1970s, the following judgement was widely expressed and appeared well founded: ‘It seems safe to predict that unemployment will never again be more than a fraction of the amount suffered between the wars’ (Stewart 1972, 296–7).

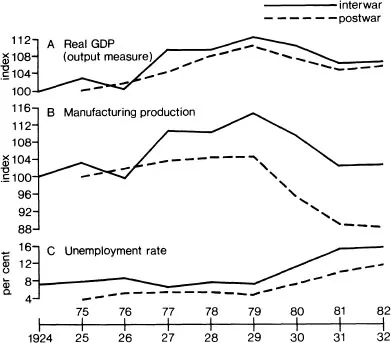

Figure 1.1 The British economy 1924–32 and 1975–82

Sources: 1924–32: Feinstein (1972, tables 6, 51, 57). 1975–82: HMSO (1983, 6, 28, 36).

In so far as history reflects current concerns as well as a genuine interest in the past for its own sake, then this study cannot evade our current crisis of unemployment. The numbers unemployed today are rather more than a ‘fraction’ of interwar levels, indeed they are actually comparable to the worst of the earlier depression period. Our current depression, the seriousness of which is revealed by figure 1.1, and its initiation by the retreat from demand management to the Thatcher monetarist experiment (Blackaby 1979; Buiter and Miller 1981), can hardly fail to alter the filters through which we view the 1930s depression and policy debate. Conversely, our attitude towards the present depression is very likely informed by our understanding of its predecessor. That this understanding is frequently suspect has proved an additional motive for the writing of this book.

Thus, in examining the 1930s policy debate, parallels with more recent periods are pursued whenever legitimate. The attractions, both political and intellectual, of budgetary orthodoxy during periods of economic crisis are investigated. So also are the results of eschewing deficit-financing in face of mass unemployment. Here a cyclically-adjusted budget measure is used to show that governments, at times of rising unemployment, ignore at their peril the effects of automatic stabilizers upon budgetary stability. More broadly, the study suggests that there are marked similarities between the questions facing both economists and policy-makers in the 1930s and 1980s, and that our strategy towards the present might usefully be informed by a knowledge of the past.

As with other recent studies of interwar economic policy, the government policy documents from the Public Record Office (PRO) have been the main source for information about policy-making. I have, however, been mindful of the problems associated with this source, in particular that ‘To concentrate on the State papers is to concentrate on the administrative processes of policy-making rather than on the causes and effects of policy’ (Booth and Glynn 1979, 315). Consequently, the PRO papers have been supplemented by the use of certain private papers, namely those of the Federation of British Industries (FBI), Neville Chamberlain (CP) and Maynard Keynes (KP). This study also rests upon a reading of the period’s financial press and a thorough review of the extensive secondary literature.

* * *

The following three chapters constitute the second part of this study. Chapter 5 considers the interwar budget accounts and budgetary practices as well as the light that these cast upon our interpretation of adherence to budgetary orthodoxy; it also introduces the related issues of the ‘Treasury view’ and ‘crowding-out’. Chapter 6 summarizes 1930s budgetary history. In particular, it details how the financial demands of the rearmament programme of the later 1930s resulted in important changes in the budget as a policy instrument. Using the constant employment budget measure, the fiscal stance of the authorities and the way in which this was influenced by the characteristics of the fiscal system are discussed in chapter 7.

The final part of the book examines the fiscal policy debate from a broader perspective. Chapter 8 is devoted to public works and the ‘Treasury view’. The theoretical differences between Keynes and the Treasury are examined, and an interpretation of the ‘Treasury view’ propounded which, for the first time, integrates theoretical, political and bureaucratic factors in order to show how, and why, by 1939 at least, there was still little common ground between the Treasury and Keynesian views. Chapter 9 concludes by examining questions of a more enduring nature, ones relevant to both the 1930s and present conditions. The political-psychological attractions of balanced budgets in the 1930s are discussed; the unsatisfactory form of economic debate in Britain, the administrative ethos of the British civil service, and connected economic-political issues also receive attention in our explanation of why demands for sound finance have proved the most robust recurrent theme in twentieth-century British economic policy.

Before proceeding to our task, however, let us first complete our introduction to the 1930s fiscal policy debate, its main issues and its various interpretations. From this we can then identify key questions for later consideration.

* * *

The history of the 1930s fiscal policy debate has hitherto been largely a Keynesian history (see, for example, Stewart 1972 and Winch 1972). It has been founded both upon a personal sympathy with Keynes, for having to endure such a sustained combat against an obscurantist Treasury, and upon the judgement that if only Keynes’s policy prescriptions had been adopted the interwar unemployment problem would have been satisfactorily resolved. Thus Joan Robinson (1976, 71), a leading exponent of the ‘new’ economics,1 typically described the debate as ‘the familiar tale of the hard-fought victory of the theory of effective demand’.

It follows that in studying the interaction between economic thought and policy between the wars, research should have primarily focused upon the gradual evolution of Keynes’s policy prescriptions and theoretical writings. Culminating in the General Theory (Keynes 1936), and finding eventual acceptance and expression by the Treasury in Kingsley Wood’s 1941 budget (Hansard 1941; HMSO 1941) and the 1944 Employment Policy White Paper (HMSO 1944), this Keynesian explanation has been couched in terms of the Treasury, guided solely by economic objectives, succumbing by the force of reason to the theoretical correctness of the ‘new’ economics.

In this view, the gradual refinement of Keynes’s theories holds the key to an understanding of the 1930s policy debate. Accepting Keynes’s (1933, 350) accusation that the Treasury and wider opinion were ‘trying to solve the problem of unemployment with a theory which is based on the assumption that there is no unemployment’, then by inference policy must change as the developing ‘new’ economics systematically undermined the Treasury’s classical economic foundations for its policies. For example, the first biography of Keynes, by Harrod (1951, 340), typifies this approach, as instanced by the following account of a lecture given by Keynes to the Liberal Summer School of 1924:

Watching his enthusiasm on the one side and the comparative apathy of his audience on the other, I felt that there was some missing clue, something unexplained….

There was indeed a missing clue. The task of discovering that clue was to occupy the next twelve years of his life. What was lacking was an explanation in terms of fundamental economic theory of the causes of unemployment.

As Skidelsky (1975b, 89) rightly comments: ‘The implication here is that had this “missing clue” been discovered in 1924, the Keynesian Revolution would have taken place there and then.’

This essentially Keynesian history thus suffers from a particular developmental bias, an undue prominence given to theory. It is not so much incorrect as incomplete, for it excludes the political dimension of these developments. During the 1930s the Treasury objected to the ‘new’ economics, and more generally to those advocating a more enlightened and active stabilization policy, on grounds not only economic in character but more fundamentally political and administrative. Similarly, the acceptance of the ‘new’ economics during the war years is explicable in terms of a change in political attitudes and prevailing administrative conditions, as well as the conversion to the Keynesian theoretical position.

Our reappraisal of this policy debate, however, needs to be conducted with extreme caution, lest either we swing too far to the opposite extreme and discount theory altogether or alternatively interpret Keynes’s concern with theory too narrowly. Certainly Keynes thought deficiencies of theory the fundamental problem, but he was far from oblivious of his political surroundings. Rather, as we shall see, more important problems were the manner of Keynes’s interpretation of the theoretical debate, and certain political presuppositions which guided both his conduct of the debate and the form of his policy advice.

Accordingly, the interpretation offered here of the 1930s fiscal policy debate is one founded upon a synthesis of the political and administrative, as well as the more normally cited economic-theoretic, constraints to acceptance of Keynesian principles of budgetary policy. No particular originality is claimed for this approach; rather, that it merely revives and makes explicit what hitherto has been muted or implicit in the literature of the period, though it does permit a more informed, and very different, specification of the issues of theory that actually divided the ‘new’ economics and the official orthodoxy.

The admission of a substantial element of non-economic considerations to this study broadens considerably the issues requiring discussion. The breadth and diversity of questions thus raised can best be introduced by reference to the most frequently suggested fiscal stimulus of the period, that of a large-scale loan-financed public works programme. At this stage we can classify the various issues associated with such a proposal under four broad headings:

1 Economic-philosophical

2 Political

3 Administrative

4 Technical

As regards the economic-philosophical issues, had this policy been adopted questions would have been raised about the viability of the belief in the powers of spontaneous rejuvenation of the free market economy. The policy might have acted as a precedent, encouraging entrepreneurs to seek broader state assistance, and thereby threatened a debilitation of entrepreneurial independence. This independence, of course, was perceived as an essential foundation of the minimalist state. Broader questions would also have been raised about the power of the state and its command of resources; with a larger proportion of final demand now not subject to ordinary market disciplines, the scope for resource misallo-cation, and thus growth inhibiting actions, was accordingly more pronounced, with obvious implications.

The political dimension results from the decision to pursue such a policy, which in turn must invariably have resulted from a greater priority being ascribed to reducing unemployment than was in fact the case during the interwar period. Thus we need to investigate why, in Lloyd George’s words, unemployment was never treated ‘in the same spirit as the emergencies of the War’ (Liberal Party 1929, 6). We need to admit the possibility that, after the experience of the inflationary boom of 1919–20 and its attendant labour unrest, the authorities might actually have preferred some measure of unemployment as a means of disciplining organized labour. We need also to acknowledge the interwar Treasury’s preference for policy instruments which, in a sense to be defined later, were ‘politically neutral’. These served both a practical purpose, that of limiting the criticism of existing policies, and a broader political principle, that of avoiding discrimination between individuals and groups which might undermine the free market economy.

The administrative issues, that ‘All policies have conditions of existence outside the minds of those who determine policy’ (Tomlinson 1981b, 4), necessitate study of the principal institutions responsible for formulating and executing policy. Accordingly, chapter 3 is devoted to a study of the Treasury and local government relations.

Finally, a discussion of institutions raises certain technical issues, in particular those concerning the volume and quality of economic information available to policy-makers. If Grant’s (1967, vi) judgement be correct, that ‘Britain between the Wars was not only a country of excessive unemployment but of inadequate statistics’, then we need to consider the implications of this for fiscal policy. In so doing, it will become apparent that the effects of bureaucratic conservatism were not confined to economic information, that it affected a whole range of other technical issues, and thereby acted as a powerful constraint upon the adoption of more active and ambitious macroeconomic policies.

* * *

The economic context within which a Keynesian fiscal stimulus would have had to operate is also of importance. We need, therefore, to introduce the issue of the performance of the real economy between the wars.

This is best done through Broadberry’s (1982) taxonomy of the interwar economic historiography, a compendium of which is given in figure 1.2. Here a distinction is drawn between two genera (pessimists and optimists) and two species or variants (old and new). The terms ‘pessimist’ and ‘optimist’ refer to assessments of the efficiency of the market mechanism in resource allocation and thus to the justification for policy intervention, ‘pessimists’ for example judging the market inefficient and the economy as thus requiring a demand stimulus. The ‘old’ and ‘new’ of the taxonomy refer to the chronology of the historiography and the methodology upon which it is founded. Thus the ‘old’, for example, is characterized by a traditional, largely non-quantitative methodology, whereas the ‘new’ (mirroring the new of the so-called ‘new economic history’) is inspired by econometric investigations and recent developments in Keynesian macroeconomic disequilibria theory (see Malinvaud 1977).

From the end of the Second World War until the early 1960s or thereabouts, the old pessimists’ interpretation of the interwar period went unchallenged: it was the orthodoxy that the economic performance of the interwar British economy was seriously deficient, that the high unemployment of the period was a clear manifestation of market failure, and that a Keynesian fiscal stimulus would have been entirely appropriate. The old optimists were not of this opinion, their challenge to the prevailing orthodoxy being founded upon certain new statistical series which suggested a much improved growth performance. Contemporaneously, there was initiated what was to become the infamous old-new industries debate (see Alford 1972, ch. 2), the old optimists claiming that the period...