![]()

CHAPTER I

The American Business Cycle,

1945 to 1967

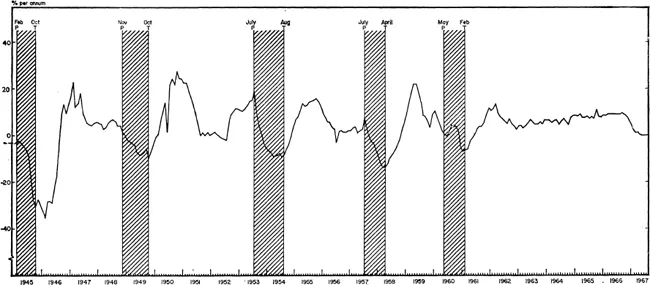

Since 1945 the United States economy has continued to experience alternating recessions and expansions in business activity. Leaving aside the fall in output following the end of the Second World War, there have been serious recessions in 1948–49, 1953–54, 1957–58 and 1960–61 when industrial production and employment fell sharply and for several months. Each was followed by an equally rapid, though short-lived (except in 1950), rise in output. In 1950 the expansion was prolonged by the Korean War rearmament. As well as these major fluctuations in activity there were marked pauses in expansions—substantial declines in the rate of growth—in 1951–52, 1962–63 and 1967. The fluctuations in the rate of growth of U.S. industrial output are shown in Fig. 1.1 which also indicates the conventional periods of business cycle expansion (from trough to peak in business activity) and contraction or recession (from peak to trough) determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. These postwar fluctuations differ from those of the interwar period in several ways. As Table 1.1 shows, leaving aside the wartime expansion of 1938–45, postwar expansions have typically lasted longer than those in the interwar period, while postwar contractions have typically been of shorter duration than those earlier. More important, perhaps, is the fact that the extent of contractions, measured by the declines in industrial production, has been much less severe since 1945 than before. After the economy made its rapid conversion from war to peace in 1945, in not one of the four succeeding recessions did industrial production fall more than 15 per cent. In 1920–21, 1923–24 and 1937–38 the falls were much greater, while that of 1929–33 was disastrous. Only the 1926–27 fall was lighter than those after 1945. This mildness of postwar recessions is the main explanation of the absence since the end of the war of prolonged bouts of mass unemployment like those in 1921–22 and throughout the decade of the 1930s.

Fig 1.1: Rate of Change of U.S. Industrial Production.

Source: FRB. Shaded areas represent periods of contraction determined by NBER as in Table 1.1.

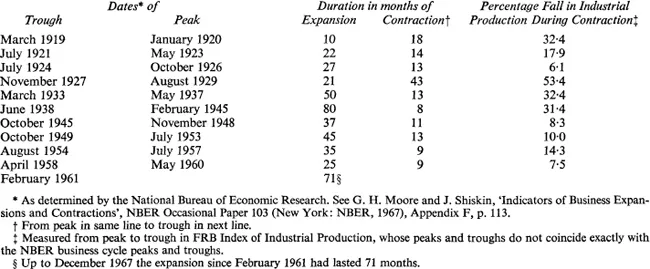

TABLE 1.1: Chronology and Severity of U.S. Business Cycles 1919 to 1967

Yet despite the improvement in the performance of the American economy, fluctuations persist and have severe effects on the welfare of both the United States and the world overseas. Between March 1957 and July 1958, unemployment rose from 3·8 per cent to 7·5 per cent of the labour force, and again between May 1960 and May 1961 it jumped from 5·2 per cent to 7·1 per cent which represents an increase of about 1·4 million people. In most recessions the volume of American imports has fallen and prices of internationally traded goods declined, usually creating balance of payments problems and pauses in growth for many developing and developed countries. Fluctuations in American economic activity are still of concern both domestically and internationally.

This chapter provides a survey of postwar fluctuations in activity, together with an outline of a model which provides a useful framework within which the fluctuations can be understood. A brief discussion of the relative importance of regular and irregular influences on household, business and government behaviour concludes the chapter: these influences are explored in greater detail in the subsequent chapters and notes. To allow this chapter to be a short introduction to the subject supporting statistics and authorities are not referred to: it is in effect a preview of things to come, and the student will find references in the subsequent chapters, notes and bibliography.

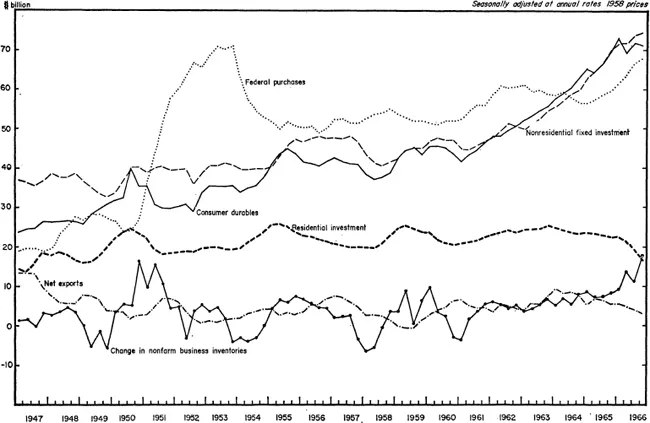

RECONSTRUCTION CYCLE, 1945–50

The decline in output at the end of the war was due to the rapid ending of defence production and demobilization. After delays due to shortages and strikes civilian production rose in early 1946 to satisfy a high level of demand for all goods and services, partly due to the desire of consumers and businessmen to restock, partly to the exceptionally large hoards of savings accumulated during the war, and partly to the strong demand for exports financed by U.S. loans and grants. This boom sustained the economy until the end of 1947. The propensity to consume did not return to normal levels until early 1948 while fixed investment did not start to taper off until the same time. (Changes in components of national expenditure are shown in Fig. 1.2.) Exports declined from mid-1947 as European countries used up their credits or satisfied their immediate needs. Although some serious shortages still persisted—steel and automobiles were the most prominent—excess demand by all indications disappeared during the first half of 1948. The postwar price rise reached its peak in January 1948 after which levels began to decline. Pressure on the labour market—measured by hours worked—eased after January and continued to relax during the year. As final demand stopped rising most sectors of business attempted to reduce inventory investment. In the second half of 1948 cutbacks in production became general, although total inventories did not fall until the second quarter of 1949.

Fig. 1.2: Unstable components of U.S. gross national product.

Source: SCB.

The recession in production was not matched by a fall in consumer spending. Consumer spending was sustained by four factors. First, the income fall was to some extent made up by reduced tax payments and transfers. Second, the marginal propensity to consume rose to maintain spending per head on nondurables and services. Third, the general recession made steel and hence cars freely available (for the first time since 1941) and a very great boom in car buying started right at the beginning of the recession. Finally, a fall in retail prices restored a large part of the purchasing power lost by the money income fall.1 In the face of sustained consumer spending, inventories in mid-1949 became excessively low, and re-ordering by business started in the third quarter of the year. The process of recovery was interrupted by a severe steel strike in October—the strike itself was preceded by anticipatory restocking, and its effects were still evident in lower than normal inventories in mid-1950—but recovery with rising output, incomes and employment was resumed in the early months of 1950. Fixed investment and exports remained at a low level.

The influences of government and agriculture complicate this story. That of government took several forms. Firstly, in late 1947 rearmament began, and defence expenditures rose until mid-1949. During the final quarter of 1947, when fears of inflation were strong, interest rates were raised and there was a general credit squeeze. The most obvious and important effect was a stifling of the residential mortgage market. Until then the building industry had been booming. After the end of the year new housing starts declined sharply and residential construction fell after mid-1948. The decline was short lived: interest rates started to fall again in early 1949 and with the mortgage market easing again housing starts rose. During the second half of 1949 construction was a powerful force for recovery. Nevertheless in late 1948 the recession in housebuilding both in its direct effect, as well as its influence on inventory accumulation and production of building materials and on purchases of household furnishings and equipment, was a significant factor in the general downturn. Other actions of government were clearly expansionary in late 1948 and early 1949: increased foreign aid, the income tax reductions in the 1948 Revenue Act and the measures to stabilize farm incomes (see below). The overall effect of Federal fiscal actions which had on balance been deflationary in 1947 and early 1948, became clearly expansionary during the course of 1948. This change was reinforced in early 1949 by the operation of the ‘automatic’ fiscal stabilizers—falls in tax receipts and increases in transfers caused by the decline in business activity.

The second complicating influence is agriculture. After a series of poor harvests and heavy foreign demand for wheat, the U.S. in 1948 experienced an exceptionally large grain harvest. Early prospects of this caused the first break in agricultural prices in January 1948 and after the middle of the year the falling grain prices were causing meat prices to decline also. The resulting large fall in food prices (together with a fall in cotton and hence textile prices) was responsible for the fall in the cost of living in early 1949. The Federal Government responded to the fall in prices in the second half of 1948 and in 1949 with substantial loans and purchases under the agricultural support policies, but despite this farmers’ incomes fell by nearly one-third between mid-1948 and mid-1949. The significance of this fall is that after reduction in tax and increases in transfers are allowed for, the fall in total personal disposable income over this twelve month period roughly equals the fall in farm income. This fall was partly compensated by the effect on consumption of the price fall.

The 1948–49 recession was caused by a reduction in growth in aggregate demand which precipitated a fall in inventory investment. The reduced growth of demand reflected primarily the end of the postwar restocking boom in which consumers filled their cupboards and wardrobes (but not their garages), and businessmen restored their inventories and productive capacity; it also resulted from autonomous factors of which the declines in residential building and exports and the fall in farm incomes, were the most important. The fall in inventory investment led to cutbacks in output, employment and incomes, but the declines were of short duration because actual inventory levels quickly fell below desired levels. This was partly due to the short-run stability of consumption of nondurable goods; it was also partly due to a rising Federal deficit and the large rise in automobile purchases due to the increasing availability of steel. By mid-1949 the agricultural changes had ceased to be depressing and were on balance expansionary—farm incomes had stopped falling and declines in retail prices were raising real incomes.

There were at least two inevitable features of the recession. First, after the end of the war business had increased fixed investment to carry out replacements of assets deferred during the war, and to raise civilian production capacity to the expected postwar levels. These levels on the whole were correctly anticipated, and once the capacity was installed excess demand was removed from both directions: supplies became more freely available and demand for capital goods declined. Second, exports had to decline from their abnormally high 1946 and 1947 levels. By contrast one feature was definitely not inevitable: the decline in residential construction; and there was one which probably could not be foreseen: the good harvest of 1948. The marginal propensity to consume was an uncertain factor: it had to decline from its abnormally high 1947 level, but in 1948 the timing of the decline and the effect on it of developments in the car market were unpredictable.

KOREAN CYCLE, 1950–54

In June 1950 the U.S. economy was again operating at a high level of activity. Residential construction was expanding rapidly, inventory investment was rising and the car market was for the first time since 1941 approaching an equilibrium. Industrial employment and hours worked were high (although the unemployment rate was relatively high largely due to the decline in farm employment). For the first time since the late 1920s the U.S. economy was booming without the special stimulus of war or postwar recovery. How long this boom would have lasted, uninterrupted by other events, cannot be measured. With industrial fixed investment starting to pick up again at mid-year, it would almost certainly have continued well into 1951. But the outbreak of the Korean War at the end of June altered every plan.

On the economy the Korean War had two main effects. It caused first a great burst of household buying and inventory accumulation which pulled the output of consumer goods—both durables and nondurables—to high levels. The consumer buying came in two bursts: in the months immediately following the U.S. involvement in the war, and again in the two or three months after the Chinese intervention at the end of November. Part of the increases was due to rising incomes; but a distinct part was for hoarding semi-durables like processed foods and textiles which it was feared would become scarce and for buying durables like cars the production of which might cease as happened during World War II. The second wave of buying subsided in the second quarter of 1951, mainly of its own accord: consumers had in a short period of time bought the durable goods which normally they would have bought over a much longer period: this bunching of purchases was inevitably followed by a fall in demand. Government controls may have had some effect on speculative behaviour: controls on consumer credit were imposed as early as September 1950, and on residential credit in October. Price and wage ceilings set at the end of January 1951 removed the incentive to anticipate price increases. Faced with a tightening mortgage market at the end of July 1950 (the result of official action) housing starts fell after August.

Inventories of consumer goods rose in the final quarter of 1950—the lull between the two bursts of consumer demand—and in the second quarter of 1951 when consumer demand had started to decline. After the first quarter of 1951 retailers found their inventories too high and their attempts to reduce their inventories together with falling sales led to a general fall in the production of consumer goods in the second and third quarters of 1951. This output—especially of durable goods—stayed at a low level until the second half of 1952.

The second main effect of the war was to launch a large rearmament programme. The initial plans laid in 1950 envisaged a gradual rise in the size of the armed forces and in defence production until the mid-1950s when the maximum threat from Russia and her allies was expected. The Chinese intervention caused the date of the maximum threat and the peak defence build-up to be brought forward to 1952–53. The armed forces expanded from just over 1 millions in early 1950 to about 3 millions in early 1952. Defence production rose rapidly from August 1950 to the second quarter of 1951, after which it continued to rise for the next two years but at a slower rate. In the early stages, parallel with the placing of military orders, a rapid rise occurred in the inventories of durable goods manufacturers. From mid-1951 to mid-1952 the level of aggregate activity was remarkably steady. Rising defence production took up the slack left by falling inventory investment and reduced production of consumer goods. The percentage of unemployed in the civili...