![]()

INTRODUCTION

Both the causes and consequences of demographic expansion afflicting the under-developed countries are so well known that it will suffice in the present chapter to deal briefly with a few quantitative facts.

The chapter is divided into two parts. The first is devoted to the long-term changes of population between 1900 and 1970, continent by continent and for the whole of the Third World. Details relating to separate countries will be found in the synoptic table which appears in the Appendix (p. 244) and which includes population in 1970 and the rates of demographic growth from 1960 to 1970 for most of the under-developed territories. The second part of the chapter will deal mainly with recent changes in birth rates and, very briefly, with population projections.

A. Changes in population of the under-developed countries from 1900 to 1970

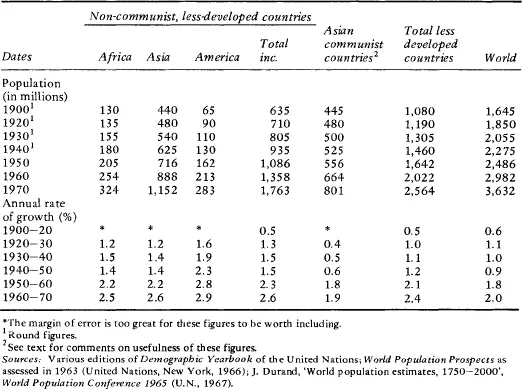

Table 1 has been constructed on the basis of information published by the statistical office of the United Nations. With the exception of data prior to 1950, the table is based on the latest issue (for 1972) of the demographic year book (New York, 1973). It should be noted (a) that figures prior to 1950 contain a margin of error which gets progressively larger the earlier the period to which they refer and (b) that the data from 1900 to 1940 has been adjusted in order to take account of recent corrections made in the 1950 figures.

Table 1 Changes in the population of the less-developed countries and of the world

Data relating to the communist countries must be considered as approximate only, since so little is known about the population of China which, in fact, dominates the total. The figures reproduced here are taken from the demographic year books of the United Nations and assume a rate of population growth of 1.8 per cent per annum for the period 1950 to 1970. However, it appears after examination of the literature relating to Chinese demographic problems1 that actual rates of growth were higher. From 1950 to 1957, a period during which figures were published by the Chinese authorities, demographic growth was of the order of 2.1 per cent. From 1957 to 1970 the indications are fragmentary and very crude. It appears that after the ‘census’ of 1953 new censuses or counts were undertaken in 1958 and in 1964: but, up till now, no results for 1964 have been made public. Since the cultural revolution the data is obviously even more uncertain. The only ‘official’ figure recently divulged was, first of all, 750 million, then 700 million, without in either case indicating the year to which the figure relates.2 This naturally leaves us to imagine that it refers to the 1964 ‘census’. Klatt is probably right when he writes that ‘nobody inside or outside China is likely to know the true size of the country’s population’; he himself keeps the figure of 750 million for 1970/71. But in Field’s view the figure should lie somewhere between the lower and the higher hypothesis resulting from the calculations in Aird’s well-documented study, that is to say, between 788 and 814 million in 1970.3 In my opinion the figure of 750 million is probably too low, since if the censuses or counts of 1953 (582.6 million) and 1958 (646.5 million) are taken as a basis, we obtain an annual rate of growth between those two dates of 2.1 per cent, and, between 1958 and 1970 of only 1.2 per cent, which is obviously too low. For this reason a figure for 1970 slightly below the average of Aird’s two hypotheses, i.e. 800 million (in mid-year), is preferred here. In my view, therefore, instead of the figure of 801 million inhabitants for the total population of the communist less-developed countries in 1970, as accepted by the United Nations, a figure of the order of 840 million would be nearer reality.

In the absense of any more valid information, the statistical office of the United Nations, until the Monthly Statistical Bulletin for August 1971, were content to add 10 million each year to the figure of China’s population in the preceding year. These 10 million represent an annual growth for 1958 of the order of 1.6 per cent which is rather low, but for 1970 they represent no more than 1.3 per cent, which is most certainly too low. Since August 1971, however, the data has been revised upwards and the statistical office now postulates an annual rate of growth of 1.8 per cent, which is probably nearer the truth.

Always allowing for margins of error, there are three phases of population change in the Third World that can be distinguished between 1900 and 1970. The first, which begins well before 1900 and lasts until about 1920, is characterized by what one might call the demographic evolution of a traditional or ancien régime economy, i.e. by a population movement marked by short-term variations of a positive or negative kind related to harvests or epidemics, and whose average rate of growth over longer periods was very low (well below 1 per cent per annum). During this period the factors of demographic change were birth and death rates which were equally high, i.e. crude rates of the order of 40 per thousand. It should be noted, however, that in a large number of regions population change was being, or had already been, influenced by the introduction of western medical techniques.

From 1910–20 until about 1950, a second phase can be distinguished which marked a break with traditional demographic trends. During these decades appeared the first signs of that demographic inflation which has recently been so widely and justifiably discussed. Population growth reached about 1.2 per cent, which, relative to previous change, constituted a marked acceleration. It was caused, as already noted, by a heavy fall in mortality due to medical progress and by a largely unchanged birth rate. Around 1950 the crude mortality rate was of the order of 25 per thousand.

Towards the end of the second world war a third phase began, marked by a genuine demographic inflation: the rates of growth of the non-communist under-developed countries, which were around 2 per cent in the first half of the ’fifties, exceeded 2.2 per cent in the second half of the decade, rose to slightly less than 2.5 per cent between 1960 and 1965, and a little over 2.6 per cent between 1965 and 1970. As we shall see shortly, it is probable that they will rise still higher in the years to come.

Population growth in Latin America has been noticeably higher since the very beginning of the period under consideration. In the early decades the difference may have been due to migrations, while in the more recent period larger available food resources probably account for the difference. At the present moment the population in that continent is growing at the rate of 2.9 per cent, as against 2.5 per cent for Africa and 2.7 per cent for Asia.

In the countries which began their development in the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the forty or sixty years preceding the start of their industrial development experienced an average rate of population increase of less than 0.5 per cent per annum, while during the first sixty years of their ‘take off’ the rate was about 0.7 per cent per annum. There is thus a very wide gap between the rate of demographic growth of the developed countries at the time of their ‘take off’ and the rates experienced currently by the undeveloped countries. And to the extent to which such comparisons are valid, it is significant that the difference between the population growth of countries which had their industrial revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the present demographic inflation of the less-developed countries is quite wide – less than 0.5 per cent on the one hand and 2.6 per cent on the other.

B. Recent changes and future prospects

We have just seen that a very marked acceleration of population growth has recently taken place. However, when the earlier estimates are examined it will be seen that these tended generally to under-estimate population growth.

To illustrate this situation we shall take the case of the most populated of the non-communist, under-developed countries. From 1951 to 1961 the official estimates for India postulated a demographic growth of 1.4 per cent per annum. However, if we refer to the census of 1961, we find that the actual progression registered was 2 per cent.4 The calculations of the Central Statistical Organization of India, made in 1959, anticipated a population of 480 million in 1966; new forecasts, made in 1962, gave a figure of 492 million.5

The same sort of under-estimation can be seen in most of the less-developed countries. However, it appears that the situation is slightly different in China (although the evidence is too unreliable for us to be able to pronounce confidently on this aspect of the problem) where population growth does not seem to have accelerated. As regards government policy, the following changes occurred; a violent anti-birth policy was succeeded in 1958 (after the Great Leap Forward) by a marked pro-birth policy: there was propaganda in favour of births, and there were perhaps even (although the facts are not very clear) measures in favour of large families. With the bad harvests of the years 1959–62 there was a return to an anti-birth policy which appeared to be still in force at the time of the cultural revolution. Information since then is not any easier to come by. Suffice it to say – and this does not indicate any change of official policy – that, according to visitors to the Canton fair,6 the pill was on sale at a reasonable price in Chinese towns and villages and that it was manufactured locally.

However, demographic expansion in non-communist, less-developed countries does not necessary imply that no recent progress has been made in reducing fertility. Taking the present age structure of the Third World population, even a considerable reduction of fertility would not retard population growth in the short term. The lack of even relatively complete statistics of recent date certainly does not help one to form an objective appreciation of the situation. Even for crude birth rates regular annual data is available for only a few countries.

The absence of recent censuses in most under-developed countries makes the calculation of fertility rates even more hazardous. On the basis of statistics or estimates of crude birth rates, it would appear that a small number of countries have experienced reductions in this rate sufficiently important to establish the probability of a measurable reduction in fertility. But it has taken place only in small countries, such as Taiwan, Puerto Rico, Hong Kong, Mauritius, Trinidad and Tobago, etc, which have already benefited from some economic and social development and have received a large volume of aid. They have also undertaken birth-control campaigns of a thoroughness which would be out of the question in the larger countries. It is in these larger countries, of course, that the problem is really crucial, and it does not appear from an analysis of the crude birth rates that any significant progress has been achieved, since any plans for birth control have usually encountered many obstacles, particularly social ones.

The difficulties met with by campaigns to regulate births can be better illustrated by reports of actual experience than by global statistics. West Bengal, where the Indian authorities had made a special effort to promote a programme of fitting the intra-uterine device, will be taken as an example. According to the latest information this programme has largely failed. There has been a steady fall in the number of women accepting insertion. The number fell from 121,000 between October 1965 and March 1966 to 51,000 between April 1966 and September 1966, while it was only 72,000 for the whole of the following year, i.e. from October 1966 to September 1967.7 This failure was mainly due to the fact that the effectiveness of the device was discredited through the personnel responsible not being sufficiently trained to deal with the many attendant medical problems. Even the vasectomy programme experienced a certain degree of failure in this region, because men undergoing the operation were not told that sterilization would not be effective until about three months afterwards. This was undoubtedly the cause of many births reported subsequently and it tended to throw doubt on what is otherwise a most reliable method.

These failures, or partial failures, are echoed from many directions and show us how urgent it is to speed up the search for a contraceptive method which is geared more closely to the economic, medical and, above all, social conditions of the under-developed countries. It is, in addition, most desirable that studies of the psychological aspects should be set in motion. Only when propaganda techniques are well attuned to local mentality will the introduction of family planning have a real chance of being effective.

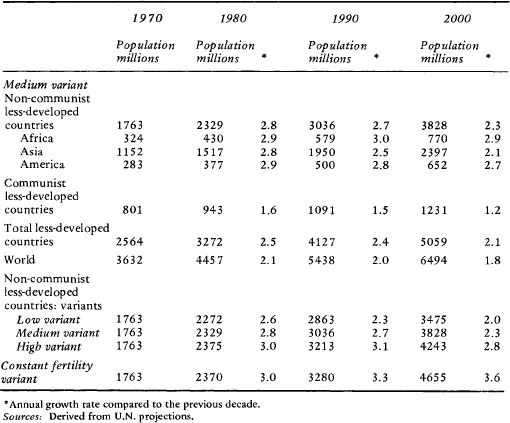

The pessimism expressed in earlier editions of this book has been confirmed by the most recent population forecasts which are given below. The figures anticipated for the less-developed countries have had to be revised upwards once more.

If we confine ourselves to the short-term prospects we have to remember that even if these birth-control campaigns are successful they can influence population levels only very slightly, since growth in the foreseeable future depends much more on the age structure of a population than on changes in its fertility. As Henry and Pressat pointed out when speaking in 19568 of the demographic outlook for the Third World, the age pyramid has such a large base that if the population is not to increase there must be either an extremely low fertility rate or an extremely high death rate. This remark is even more pertinent now, when the changes which have taken place since the middle of the ‘fifties have further enlarged the base of the Third World’s age pyramid.

Allowing for this factor and assuming that the surpluses of western agriculture (and of North America in particular) would be capable of fending off for at least ten to fifteen years the risks of famine in the less-developed countries, we can expect with reasonable certainty that the rate of population growth of the Third World will increase in the course of the next ten years, probably up to 1980.9 For this period we can assume as probable an annual rate of growth of around 2.8 to 2.9 per cent for the non-communist, under-developed countries, at least.

Table 2 Projection of population for less-developed countries and the world 1970–2000

It will be noticed that the rates I have quoted relate to the non-communist countries only. For the communist countries it would be rash to make any forecast in view of the uncertainty of the past and present data. I have, however, reproduced in Table 2, for information only, the figures compiled by the United Nations experts which summarize the population forecasts made by them for the perio...