![]()

1 The Story of Iron

Iron is the chief metal on which our civilisation today rests. Ninety-three per cent of all the metal we use is iron.

But iron is never found in its pure state in the earth. It is found as iron ore, that is iron mixed up with such substances as oxygen, sulphur, sand and perhaps clay. These are impurities not wanted in the finished iron, and the problem down the ages has been to find out how to separate the iron from these other substances. The answer is by smelting in a furnace.

Smelting iron ore

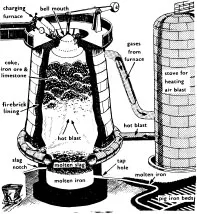

Today we do this in huge blast furnaces, where iron ore, together with coke and limestone, is subjected to a great blast of air and heated up to 1800°C. (1525°C is the temperature at which iron liquefies.)

The carbon in the coke combines with the oxygen in the iron ore to form a gas. (See the illustration.) The limestone combines with the other impurities to form liquid slag which floats on top of the molten iron and is drawn off through the slag notch. The molten iron is drawn off through the tap hole into channels of sand called pig-iron beds. It will have absorbed some of the carbon from the coke and this iron is called pig-iron or cast-iron.

Early ways of working with iron

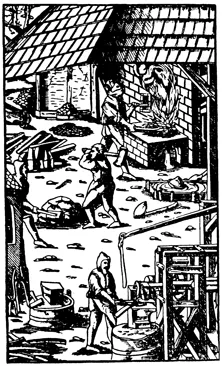

How early smiths made things from wrought-iron The first smiths built small furnaces not much more than a metre high, sometimes lined with clay, with a hole at the top and an air hole at the bottom. A charcoal fire was lit, and iron ore and charcoal were piled in. Air was blown through the hole at the bottom by bellows. Gradually the ore became soft. It never liquefied. It just became a soft lump or ‘bloom’.

After about twelve hours the furnace was opened and the lump of iron taken out. But it was too brittle to be of much use (because, as we know now, it contained so much carbon and slag).

The smith hammered the soft iron to get rid of the impurities. He now had a metal that was pure and workable, one that could be made into tools, ploughshares, etc., at the blacksmith’s forge. This is what we call wrought-iron, or worked-on iron.

Smelting with charcoal

As early as the fourteenth century in Britain, some ironmasters had found out how to reduce iron to a melted or molten state, though of course they were not able to produce a great enough heat to melt it completely. A temperature of 1525°C was needed for that.

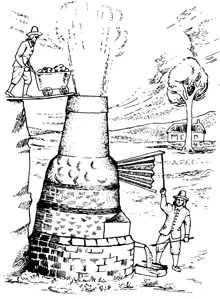

By the seventeenth century some ironmasters had built furnaces 5 to 9 metres tall, often on the sides of a hill to make it easier to unload trucks of ore and charcoal into the top of the furnace. To increase the heat of the furnace there were great bellows 7 metres long, worked by waterwheels.

The molten iron now being obtained would be run off into sandy casts called ‘pigs’ (see illustration), or taken in ladles and poured into moulds. It was found that this pig-iron was of better quality than the old blooms, but it was still very brittle. It could be used for making ornamental shapes, but finer, stronger tools and weapons continued to be made of wrought-iron in the old way.

1. A modern blast furnace

2. Making wrought-iron in the sixteenth century. The ‘bloom-smith’s’ face is protected by a mask. In his right hand he has a bar with which he stirs the iron and beats out the cinder or impurities. The man with a wooden mallet is beating the ‘bloom’ after it has been taken out of the furnace. Next this ‘bloom’ is put on the anvil (bottom right) and beaten by a hammer which is driven by a waterwheel. Finally it is cut up into four or six pieces

3. A seventeenth-century furnace for making cast-iron

4. How pig-iron got its name. When the molten iron was led off into sandy casts the process looked rather like a mother-pig feeding her piglets. Hence the term sow for the large cast, pigs for the smaller ones, and pig-iron for the molten cast-iron

The dwindling forests

The chief centres of the early iron industry in Britain naturally grew up at places where there was iron ore to be found, forests for charcoal, and water for power—the Forest of Dean and the Sussex Weald were two of the best areas. The industry could also be found in Kent, Surrey, the West Midlands, North Lancashire and round Sheffield.

However, by the sixteenth century timber was in great demand for many other things besides making charcoal—shipbuilding, house-building, furniture and fuel. Indeed it was becoming so scarce that even the government was alarmed. In 1558 Queen Elizabeth’s Parliament passed an Act forbidding the cutting down of trees for ironmaking in certain parts of England. In 1584 another Act forbade the building of any more ironworks in Surrey, Kent or Sussex. In 1674 all the royal ironworks in the Forest of Dean were closed.

5. How early charcoal-burners made charcoal

1. They made a clearing in the forest to obtain wood to build their stacks.

2. They made a circular hearth and erected a stake in its middle.

3. Lengths of wood were piled round the stake, some pieces put horizontally, some sloping to allow air to circulate.

4. The stake was removed and the hole left, to act as a chimney. Often other air holes were left around the bottom of the stack.

5. The stack was covered over with straw or brushwood and then with a layer of damp earth.

6. It was set alight with a torch and kept burning slowly until charcoal formed— that is, the wood changed into almost pure carbon. Then the top of the stack was closed off and it was left alone for five or six days.

7. When the stack was dismantled, the charcoal was sold to the iron workers for smelting iron ore. But it took six loads of wood to produce one load of charcoal, so the process used up a great deal of woodland.

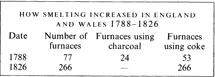

By 1740, there were only fifty-nine furnaces left in England and pig-iron was being imported in ever-increasing quantities. It looked as though the British iron industry was doomed, unless some fuel other than charcoal could be found for smelting.

Smelting with coke: the Darbys of Coalbrookdale

From time to time some ironmasters had tried to use coal instead of charcoal, but it choked the furnaces and the sulphur fumes ruined the iron. Yet as early as 1619, an ironmaster called Dud Dudley claimed to have used coal successfully. His idea was never adopted, and he blamed his failure on the opposition of jealous charcoal ironmakers and the English Civil War.

But the wars of the eighteenth century and the growing use of firearms and cannon, provided a growing market for iron.

Abraham Darby I (1678–1717) was the son of a Quaker locksmith. He set up a brass-making works at Baptist Mills near Bristol. Here he experimented with coke as fuel. Coke is made from coal. Abraham Darby covered piles of coal with clay and cinders, allowed in only a little air, and kept them smouldering for a week. The sulphur and other impurities were burnt off and the substance that remained consisted mainly of carbon. Coke creates a better heat than charcoal and, being hard, is better able to stand a heavy load on top of it.

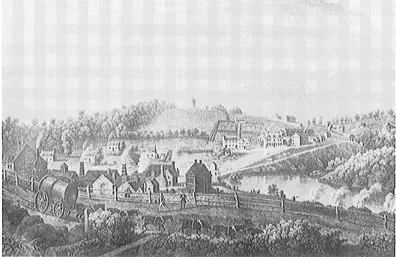

Abraham Darby moved to a small, derelict ironworks at Coalbrookdale in Shropshire and in 1709 he first smelted iron successfully with coke. Coalbrookdale had a number of advantages. Iron ore, coal and limestone could all be obtained from abundant local sources; the River Severn provided not only a source of power for bellows and hammers, but a convenient means of transporting finished iron goods to markets and customers.

In the early eighteenth century Coalbrookdale was producing kettles, pots, cauldrons and grates. Abraham Darby II (1711–63) took account of fresh needs and began to make cast-iron parts for the newly developed steam pumps and cannon. Abraham Darby III (1750–89) involved the family firm in ideas that were important in the later development of railways. In 1767, strips of cast-iron capping were put on top of wooden railway tracks for the first time to prevent them wearing out so quickly. In 1779 the firm designed and built a famous iron bridge across the Severn; it still exists today.

Coke smelting spread only slowly. It was more than a hundred years before it had completely replaced the charcoal-burning furnaces.

6. Abraham Darby’s ironworks at Coalbrookdale, Shropshire. Notice in the foreground the cylinder on a cart that is pulled by a team of horses; and beyond the fence piles of coal being coked

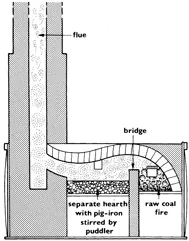

7. Henry Cort’s puddling furnace

But coal for making coke was far more plentiful than wood for making charcoal. Because of this the iron industry gradually moved away from the forest areas of the south to the great coalfields for example to South Wales, Derbyshire and Yorkshire.

Wrought-iron: Henry Cort of Gosport

The increased production of pig-iron called for new ways of producing wrought-iron in larger quantities. Although several people were experimenting with new methods, it was Henry Cort who proved successful and patented his ideas in 1784.

Puddling

Cort’s invention is best called ‘puddling and rolling’ Raw coal is burnt at one end of the furnace. The flue from which its smoke e...