- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Victorian Railwaymen

About this book

First published in 2005. Much has been written about the physical development of the railway system in Britain, the enormous investment of capital involved and the crucial effects on economic and industrial growth in the nineteenth century, but very little has been said about the most important social aspect of this phenomenon. This is a study on the emergence and growth of railway labour, in 1830-1870.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Victorian Railwaymen by P.W. Kingsford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

LABOUR ECONOMY

C h a p t e r 1

RECRUITMENT

The system and methods of recruitment were among the most important influences on the economic and social character of railway labour. The subject is discussed in this chapter under the following headings: the sources of labour or fields of recruitment and the patronage system; the standards and quality required and enforced; the difficulties, if any, in recruitment of the required quality of labour.

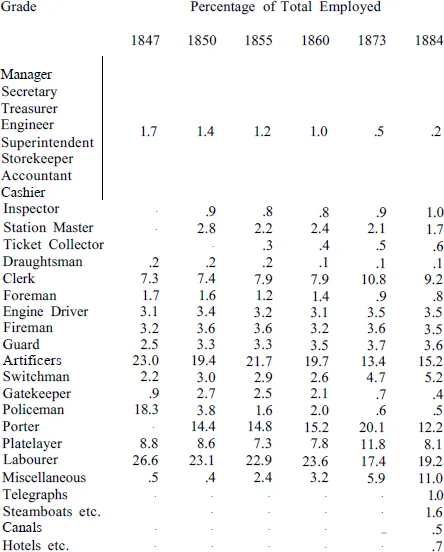

An analysis of labour employed, by the chief grades, as shown in Table II gives a preliminary idea of the problem and of the numerous types of occupation which had to be filled. The grades may be put into seven main groups: managerial, clerical, supervisory, skilled operating, unskilled, artificers, and miscellaneous. This is shown in Table III. Managerial includes managers, secretaries, enoirieers, accountants, storekeepers. Supervisory includes station masters, inspectors and foremen. Skilled includes engine drivers, guards and switchmen. Unskilled includes all others except artificers and miscellaneous. The division between skilled and unskilled has been made on the basis of the training and experience required, responsibility and wages. The figures for 1847 are incomplete and not strictly comparable with others. The low supervisory percentage in that year is accounted for by the fact that there are no figures for station masters and inspectors.

The decrease in the managerial proportion may be due to amalgamation. In spite of that development, however, the clerical and supervisory together increased considerably. The proportion between skilled and unskilled changed slightly in favour of the skilled but a considerable number of the miscellaneous must be included in the unskilled. The high percentage of miscellaneous in 1884 makes the figures for that year hardly comparable.

Table II

Persons Employed by Grades

Persons Employed by Grades

Sources of Labour

The generally accepted view that the main field of recruitment for the greater part of labour was from agriculture can be broadly confirmed. Tn agricultural districts where wages were very low, fifteen shillings per week as a commencing wage for a porter enabled the company to obtain, without difficulty, as many men as they required, especially as the chances of promotion afforded to the men a prospect of advancement far beyond what they were likely to attain in agricultural pursuits.’ This statement by a railway manager in 1879 is confirmed by an examination of applications for employment from 1840 onwards. A similar reference to the employment provided by the railways in agricultural districts was made by the 1867 Royal Commission on Railways.1 The suggestion then was that the parishes had been indirectly relieved of much pauperism. However there seems to have been little direct help to the parishes by the employment of paupers and when in 1843 the railways were requested to follow the farmers’ example by taking on unemployed men the request was passed over to the contractors with the comment that the railways could employ only ‘trained men’. In 1876 evidence given before a Parliamentary committee stated that labour was previously drawn from agricultural districts where wages were lowest. This, it was said, gave the railways a special advantage over other employers since they were put to no cost of conveyance for their workers.2 Whatever the substance of this point, local recruitment was often the rule. On the Liverpool & Manchester in 1832 out of about 600 men employed, about 540 were recruited locally. It was also the policy in 1848 on the Great Northern when, prior to opening the line, the directors ordered the porters and gatekeepers to be selected from local men.

Table III

Persons Employed by Groups

Persons Employed by Groups

| Group | Percentage of Total Employed | |||||

| 1847 | 1850 | 1855 | 1860 | 1873 | 1884 | |

| Managerial | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 | .4 | .2 |

| Clerical | 7.5 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 10.9 | 10.3 |

| Supervisory | 1.7 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 3.5 |

| Skilled | 7.8 | 9.7 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 11.9 | 12.3 |

| Unskilled | 57.8 | 56.2 | 53.0 | 54.3 | 53.6 | 44.7 |

| Artificers | 23.0 | 19.4 | 21.7 | 19.7 | 13.4 | 15.2 |

| Miscellaneous | .5 | .4 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 5.9 | 13.8 |

The broad generalisation that agriculture was the main field of recruitment requires, however, some qualification. It is largely true of the majority in the traffic grades, the men who required little skill at first, porters, police, brakesmen, switchmen and the permanent way men, the grades from which those with more skill developed. It does not apply to others such as enginemen, gangers, guards. Even in the general traffic grades, men who had been in gentlemen’s service were always acceptable. Discharged soldiers were preferred and the minimum age of entry for police and porters was raised in their favour. In the early years the railway contractors were also to some slight extent a source of supply of unskilled men. According to Edwin Chadwick railway construction labourers were either discharged, returned to agricultural work, or became vagrant and increased the prison population.1 But contractors’ men who were injured at work were often given preference for employment when the railways opened, a policy which became general as the Midland and other lines adopted it. The early police, jacks of all trades, transferred in the same way from construction to operation. When these men were first appointed they were, although paid by the railways, supervised by the local magistrates, and their duty was to preserve order among the construction labourers. Many of them were retained by the railways, after construction had been completed ‘if they conducted themselves properly’ and their duties then became those of keeping the railway line free from obstruction, which in turn developed into the work of signalling.

The police were so much the prototype of many subsequent grades, such as signalmen, switchmen and ticket collectors, that they are worth special mention. Inevitably they were modelled on the recently established Metropolitan Police, with similar uniforms and beaver top hats, and with similar wages and duties. They were sometimes recruited from the metropolitan police and city police elsewhere. In 1840 wages in London were very much the same for both, viz. railway police — 17s to 19s per week, civil police — 17s to 21s per week. But there were certain advantages and opportunities for advancement on the railways, not open to the civil police.

The enginemen were in quite a different class and from the first they showed a peculiar sense of independence. In the thirties and forties the demand for them was greater than the supply; they could ‘dictate their own terms in a great degree’. It was difficult to get skilful and reliable men. They were recruited, not from blacksmiths as one member of the 1839 Select Committee supposed, but mainly from labourers who showed a particular aptitude for the work, wherever they could be obtained. The length of training depended on that aptitude, but training presented no difficulty since the men were not required to have much knowledge of the locomotives. They were, however, ‘men of great activity and great ability to get out of a difficulty’.1 Brunei considered it an advantage if they were illiterate and many of them were so. A few no doubt, like James Hurst of the Great Western, came directly to the company from the decaying hand loom weavers without the advantage of any schooling. The engine-men, however, were almost the only men who had had some training. Their original school was the colliery lines of Northumberland and Durham, particularly Killingworth Colliery. The men trained there drove the locomotives in the north east, and enginemen from the north east were taken to the Liverpool & Manchester by George Stephenson. A little later Daniel Gooch, locomotive superintendent of the Great Western, himself a Tynesider, recruited most of his enginemen from the north, men such as the same James Hurst who, after being labourer, fireman and engine driver on the Liverpool & Manchester, became driver on the Great Western.

The previous occupations of railwaymen seem to have become somewhat more varied after the early years. In 1858 the total establishment of twenty-eight men at Sheffield passenger station showed the following previous occupations:- twelve labourers, three soldiers, two police, two domestic servants, one spinner, one ostler, one groom and four from other railways. In 1857 applicants for employment on the London & North Western included a footman applying for the post of porter, a joiner for that of foreman, a provision merch...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I. Labour Economy

- PART II. Social Economy

- Bibliography

- Index

- Appendices