![]()

Chapter 1

A CENTURY OF ECONOMIC GROWTH

In 1801 the population of Great Britain was 10.6 million; by 1901 it was 37.1 million. The national product in 1801 has been valued at £138,000,000; by 1901 it was £1,948,000,000. The rise per head was from £12.9 to £52.5 and, as these figures represent constant prices, the rise in material standards is evident, even allowing for the unequal distribution of socially created wealth. As evidence of economic growth the figures speak for themselves.

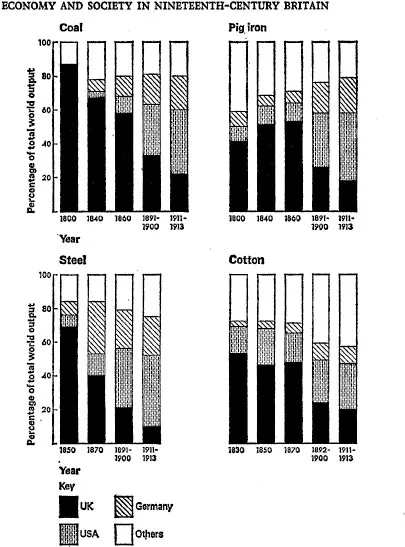

All three sectors had undergone periods of rapid expansion – agriculture in the first decade and a half of the century, industry intermittently over the next sixty years, services in the last third of the century – and their relationship to one another had changed. Agriculture declined from a position of relative dominance, to one of relative unimportance, while manufacturing industry and services (transport, retailing, commerce) took its place. The change-over was marked by the fact that cycles in trade and investment, rather than the fortunes of the domestic harvest, came to determine the general level of economic activity in any one year. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, machine-based factory industry was the exception: by the end of the century it was the rule. Not only had the coal, iron and cotton industries expanded their output to unprecedented orders of magnitude, but wholly new features had appeared to transform economic life. The railway, the steamship and the electric telegraph revolutionised communications; the mass-production of steel gave industry a new raw material; electricity gave it a new source of power. The joint-stock company and the trade union emerged as new means of mobilising the forces of capital and labour. But these changes were accomplished as a result of a jerky and untidy growth process in which chance factors like war and weather combined with the underlying forces of social and technological change to complete the work of economic transformation. This chapter attempts to present a brief outline of this process.

I Britain in a Century of Growth

1793–1815. THE REVOLUTIONARY AND NAPOLEONIC WARS

. . . the country, during a war of twenty-five years, demanding exertion and an amount of expenditure unknown at any former period, attained to a height of political power which confounded its foes and astonished its friends . . .

. . . But peace at length followed, and found Great Britain in possession of a new power in constant action, which, it may be safely stated, exceeded the labour of one hundred millions of the most industrious human beings, in the full strength of manhood. . . . Thus our country possessed, at the conclusion of the war, a productive power, which operated to the same effect as if her population had been actually increased fifteen – or twenty-fold: and this has been chiefly created within the preceding twenty-five years.

Thus Robert Owen, factory-owner, philanthropist and grandfather of British socialism, summarised the impact of the French wars on the British economy. There can be little doubt that he regarded it as a challenge to which Britain had responded magnificently by a great burst of capital investment in the new technology of steam. But the effects of the war were more complex: not merely a stimulus to growth, but a stimulus to growth in some directions and an obstacle to growth in others. And the problem of evaluation is complicated by the fact that the effects of the wars were compounded with deep and fundamental re-adjustments already under way – most notably the progress of industrialisation and agrarian change under the dual impact of a demographic revolution and startling improvement in the transport system. Granting that Owen was largely correct in his estimate, that the economy as a whole was vastly more productive after the wars, it is necessary to investigate the fortunes of each sector in some detail.

Agriculture – still the largest sector – employed one-third of the labour force and accounted for roughly the same proportion of the National Income. Rising population, military demands for horses and grain, and a more than average number of bad harvests combined to raise the demand for food quite dramatically. As imports in quantity were neither technically nor economically feasible, the way was open for British farmers to finance, by borrowing or from inflated profits, the introduction of new agricultural techniques which would enable them to exploit market opportunities to the full. The pace of enclosure quickened, advanced practices, such as selective breeding and four-course crop rotations, became more general, and new cheap, light, durable iron implements were widely adopted. The scale of investment in agriculture was so great that it has been suggested that it absorbed more capital than industry in this crucial period. The rate of enclosure, at nearly 53,000 acres per annum, was higher in the period 1802–15 than for any other period in British history, and it has been estimated that the acreage of potatoes increased by 60 per cent between 1795 and 1814.

Industry enjoyed mixed fortunes. Heavy industry obviously prospered with the demand for war material. Iron production, for instance, quadrupled between 1788 and 1806, and there can be little doubt that the use of Cort’s process for producing wrought iron with coal spread far faster than it would otherwise have done.

Wool probably benefited from the demand for uniforms, but cotton, being wholly dependent on uncertain supplies of imported raw materials, grew spasmodically. Shipbuilding expanded to make good the losses incurred at the hands of the enemy, but building marked time except on government projects like barracks or docks. The more general adoption of steam-power may have been boosted by the relatively high price of fodder for horses and the scarcity of labour due to the massive recruitment of men for the armed forces.

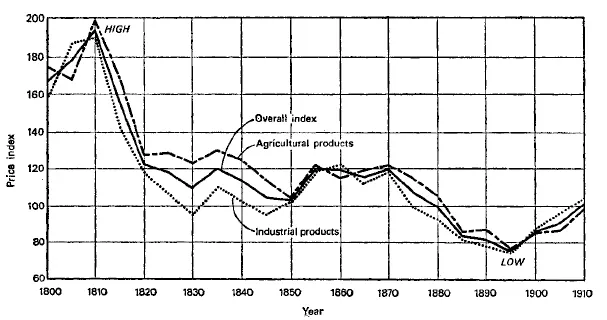

2 Rousseaux Price Indices, 1800–1913

Note: Although price data reflect in part the changing fortunes of agriculture and industry, they must be related to other indicators such as rates of growth, investment and profitability to tell the whole story.

Trade was persistently disrupted by the naval war but maintained its growth by seeking out new markets. Shut out from Europe by the ‘Continental System’, British traders found stable new markets in India and South America. The disasters of Napoleon’s Russian campaign (1812–13) broke the facade of his authority and from then onwards British goods found their way into Europe in increasing volume.

The war cost something in the region of £1,000,000,000. Part was raised by taxation, which comprised an antiquated land-tax, a novel and much-hated income-tax, tariffs on imports and various excises on domestically produced commodities (e.g. malt). The bulk of government revenue, however, came from borrowing, with the result that the National Debt rose from around £200,000,000 to over £800,000,000 – an unprecedented development which imposed heavy burdens of debt-servicing on post-war governments and even more on the poor who paid the taxes. The other major financial feature of the period was the introduction of paper currency. A French invasion scare in 1797 produced a run on gold, and the Bank of England was obliged to make its notes non-convertible. Thereafter, paper currency became generally accepted, although the increasing volume in circulation contributed materially to war-time inflation, which boosted profits and depressed living standards.

1815–42. THE CRISIS OF CAPITALISM

The post-war period was one of disturbed and uneven growth. The pace of industrialisation quickened but against a depressing background of falling prices and severe social discontent. According to P. Deane and W. A. Cole:

. . . the period of greatest structural change fell within the first three or four decades of the century, particularly in the two decades immediately following the Napoleonic wars. To some extent the post-war spurt was intensified by the effect of the war in distorting and retarding the pattern of growth; but probably this would have been a period of relatively rapid change even without a war to complicate the process. There was a substantial fall in the share of agriculture (amounting to perhaps 13 per cent to 14 per cent in the period 1811–41) and an equally substantial gain in the share of the mining, manufacturing and building groups of industries (British Economic Growth 1688–1959).

The period 1815–21 was particularly troubled. Trade, after enduring a brief re-stocking boom as goods were rushed to starved European markets, collapsed in 1818. The cessation of government orders for war material brought depression and unemployment in the iron, wool and shipbuilding industries. Agriculture was disturbed by a succession of bounteous harvests and the fear of foreign corn imports. Demobilisation released 300,000 men on to the labour market, but surplus capital, rather than seek profitable outlets by employing them, fled to the restored governments of Europe. Rapid deflation, to prepare for the resumption of cash payments (which took place in 1821), reduced the volume of money and credit, discouraging domestic investment. Falling interest rates did help the construction industry, and the consumer goods industries (like brewing and milling) picked up, but generally the period was marked by widespread social discontent. Radicals, like Orator Hunt, found large audiences ready to listen to pleas for government action and reform. The government continued to trust to political repression (e.g. Six Acts 1819) and economic fatalism.

In a sense, events justified their do-nothing policy (though they were in no danger of starving as a result of it). In 1822 European trade began to revive and with it industrial output and incomes. Foreign investment reached out to South America, which promised great things. The repeal of the Bubble Act (1825) produced a rash of joint-stock ventures. Their hopes were soon dashed by a general commercial crisis which engulfed South America and brought down many of the new companies. Heavy industry was depressed throughout 1826 and 1827 and there were bad harvests in 1828 and 1830. This scarcely helped the farmers, who were still producing more than the market needed, and necessitated moderate imports of grain which meant an outflow of gold, contracting credit and discouraging investment.

The atmosphere brightened in the early 1830s. Railway investment went through its first mania (1834–6) as eager speculators strove to imitate the success of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (opened 1830). Cotton investment soared as manufacturers switched to power-weaving. Anglo-American trade doubled between 1830 and 1836, and an enlarged flow of capital across the Atlantic strengthened the economic links between the countries. Harvests were good from 1833 to 1835 and, following the reform of Parliament and the electoral system in 1832, a great number of institutional reforms were set on foot – the Factory Act (1833), abolition of slavery (1833) the New Poor Law (1834), the Municipal Reform Act (1835), the Tithe Commutation Act (1836) and civil registration (1836).

Gloom descended again after 1836 as the American market ceased to expand. Exports to America sank from £12.5 million in 1836 to £5 million in 1837. For the first time ever cotton imports fell in two successive years. Railway investment was checked and both coal and iron were plunged into an overproduction crisis. The harvests of 1838 and 1839 were bad and in the latter year the country entered the deepest depression of the century. It brought down the reforming Whig administration (1841) and raised Chartist agitation to its height.

Professor S. G. Checkland has written:

The period from the twenties to the forties is difficult to summarise. In terms of capital formation, the development of new skills, and the increase of total output, it was a time of great progress. But in terms of improvement of real wages, though many workers were gaining ground, it is highly doubtful whether the mass of men enjoyed any great material advance. Certain groups suffered heavy direct blows, the prelude to their diminution or eclipse. Prices as a whole fell continuously, except for hectic boom intervals, suggesting in a prima facie way that the system was not reaching its full potential output (The Rise of Industrial Society in England, 1815–85).

1842–73. THE GREAT VICTORIAN BOOM

The period from 1842 to 1873 was the great Victorian boom, when spasmodic growth gave way to regular and rapid growth. The basic determinants of this phase of expansion were a continuing rise in population (a world-wide, not just a British phenomenon), the rapid construction of railways, the general exploitation of steam technology by industry, and the adoption of free trade policies. Acting and re-acting upon one another, these forces of change effectively opened up a new frontier, a vacuum of demand and a new potentiality of supply, which launched industrialisation into its second phase and gave heavy industry a pivotal role in the new economy.

Recovery from the depression of 1839–42 was initiated by the second, and greatest, ‘railway mania’. The European harvest crisis of 1846–7 brought it to a halt and for the last time commerce suffered the contractions induced by the ‘grain in–gold out’ pattern. The lag between railway promotion and railway construction, however, gave a much-needed boost at this difficult time and as a consequence Britain was saved from the revolutionary wave which engulfed Europe in 1848. The discovery of gold in Australia (1848) and California (1849) produced an atmosphere of business optimism and simultaneously provided the means to ease the problem of international payments. Exports expanded faster than industrial output, rising 130 per cent between 1842 and 1857.

The Great Exhibition (1851) demonstrated Britain’s industrial supremacy to the world and it was this industrial supremacy which was the basis of her economic dominance. As Marx and Engels rather unflatteringly put it:

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation. The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls. . . . In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

The image, at least as far as Britain went, was one of prosperity. Real wages were showing the first signs of a general move upwards. Agriculture was doing well and society was stable, and the two facts were not unrelated. Attempts were being made to improve the lethal and wretched urban environment.

The Crimean War (1854–6) boosted shipping and heavy industry, but the more general availability of limited liability status (1855) led to the mushroom growth of irresponsible and ill-managed joint-stock ventures, which were swept away by the commercial crisis precipitated by the Indian Mutiny (1857). The speed of recovery was remarkable, however, and is a testimony to the underlying optimism and resilience of the mid-Victorian economy.

From 1857 to 1866 the upward trend was resumed. A new, mass-production steel industry was born, and domestic railway construction blossomed again. Steam-technology affirmed its dominance in shipbuilding. The American Civil War (1861–5) produced a ‘cotton famine’ in Lancashire, but brought new prosperity to India, which rose from the wreckage of the Mutiny to become temporary supplier of raw materials to one of Britain’s greatest ‘staple’ industries. But the cessation of hostilities in America and the collapse of the railway boom in Britain brought disaster again to India and an end to the reckless speculations which had been encouraged by the discount houses of the City of London. The greatest of them, Overend, Gurney and Co., closed its doors in 1866. It was the most important financial institution after the Bank of England, and it brought down with it dozens of smaller discount houses, banks and railway companies. Widespread revelations of low business ethics and unsound managerial practices followed, and ‘Black Friday’ was long remembered in the City with a shudder. In retrospect, however, it might be regarded as merely a traumatic phase of ‘natural selection’, which left City institutions wiser, str...