eBook - ePub

Naval Policy and Strategy in the Mediterranean

Past, Present and Future

- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Maritime strategy and naval power in the Mediterranean touches on migration, the environment, technology, economic power, international politics and law, as well as calculations of naval strength and diplomatic manoeuvre. These broad and fundamental themes are explored in this volume.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Naval Policy and Strategy in the Mediterranean by John B. Hattendorf in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

THE PAST AS PROLOGUE

2. A Venetian galleass of the sixteenth century. A hybrid which lacked the best characteristics of oar or sail power, the galleass had a relatively brief existence as a warship type.

1

Navies and the Mediterranean in the Early Modern Period

Carla Rahn Phillips

Historians of the Mediterranean have paid considerable attention to the period 1450–1700, and for good reason. During the early modern centuries seafarers adopted new ships and sailing techniques that changed the character of trade and naval warfare. Equally important were changes in the rivalries that marked Mediterranean seafaring. After centuries in which Latin and Orthodox Christian powers had dominated the Mediterranean, the rise of the Ottomans led to a titanic clash between Christian and Muslim civilizations. In that struggle, which involved political, religious, commercial and cultural antagonisms, the diverse peoples of the Mediterranean were the major players at first. None the less, a much larger theater of rivalry extended from the Mediterranean northward to central Europe and the Black Sea and southeastward into western Asia and the Indian Ocean. During the sixteenth century, in the aftermath of the Age of Discoveries, the European center of economic and political activity shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic and beyond.1 However, in the broader context of world trade and international rivalries, the Mediterranean retained its strategic importance. During the seventeenth century European states that were primarily linked to the Atlantic world – England, Holland and France – established themselves in the Mediterranean as well.

The overview presented here will trace these developments, relying on the wealth of historical scholarship that has focused on the Mediterranean in the early modern period. Although major powers will dominate the narrative, minor powers will also appear from time to time.2 Every state in the strategic game of the Mediterranean had different perceptions, goals and method, some of which pertained only to the age of oar and sail and others of which continue to the present day. In so far as possible, the narrative that follows will try to retain those varying perceptions of reality.

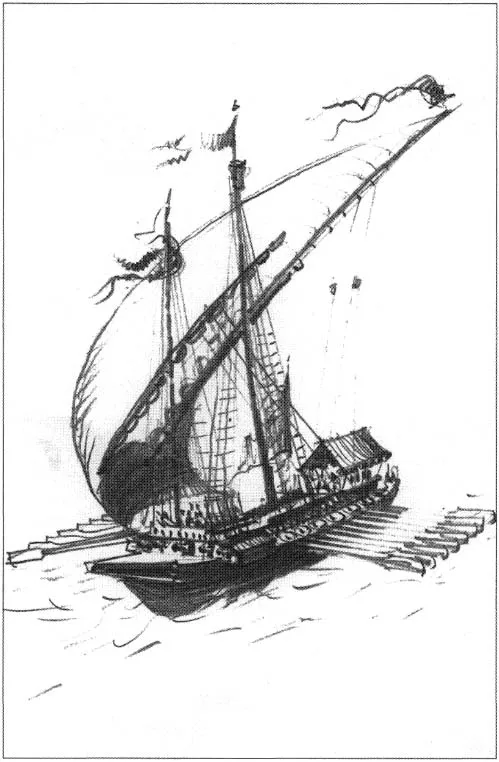

3. The Mediterranean Sea: prevailing winds in summer

It is worthwhile to sketch some of the enduring physical realities that shaped the Mediterranean as a stage for historical drama. Ecological conditions – soil and rainfall, winds and currents, ports and hinterlands, climate and seasons – had always posed a daunting challenge for inhabitants of the Mediterranean littoral. The region is rich in natural beauty but generally poor in natural resources. Some favored areas can grow nearly anything with ease, but there are vast areas that can barely be farmed at all owing to unfavorable conditions of soil, climate, topography and rainfall. Seafarers also faced difficult conditions. The prevailing winds blow from the northwest to northeast quadrant and the currents generally run counterclockwise. Winds may fail altogether in some seasons and blow at gale force in others. At choke-points, such as the Strait of Messina, strong currents, riptides and whirlpools gave rise to ancient legends of monsters beneath the boiling seas.

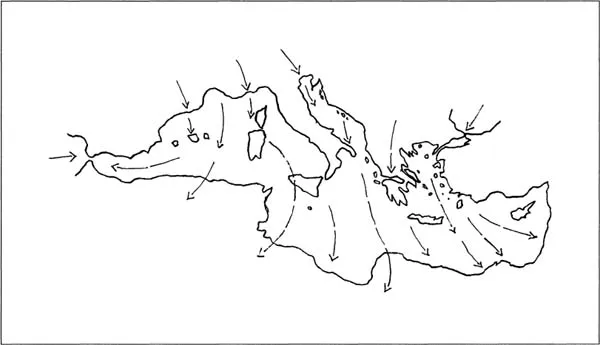

Rivers provide only about 25 per cent of the water lost through evaporation in the main body of the sea, plus another 4 per cent from the rivers that flow first into the Black Sea. The other 71 per cent of the Mediterranean’s water comes from the Atlantic Ocean, flowing in as a surface current. Until the development of the sternpost-mounted rudder and the full-rigged sail plan, from the late thirteenth to the fifteenth century, sailing ships had great difficulty making headway against contrary winds and currents. Oared ships such as galleys could concentrate enough human power to battle the elements, but they were highly vulnerable to bad weather and dangerous coastlines. None the less, what the galleys did they did very well, within the confines of the sea. Without the need regularly to confront the open ocean, Mediterranean trade and warfare continued to rely on the galley from ancient times through the sixteenth century.3

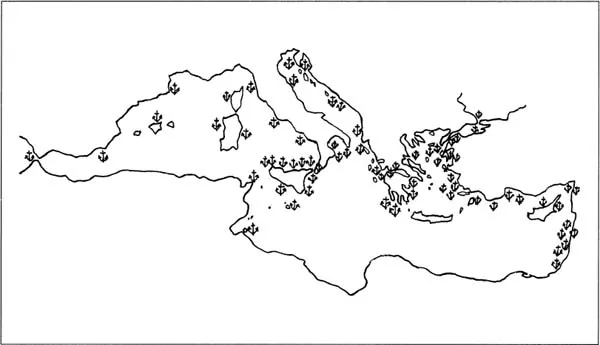

Historians of the Mediterranean often divide their discussion between the eastern and the western halves of the sea. In its physical characteristics, however, the true distinction is between north and south. In general, the southern coastline is dangerous, even without taking the winds and currents into consideration. Moreover, the best ports often suffer from insufficient supplies of fresh water, food or both, a pattern of scarcity that posed great problems for galley fleets that had to be resupplied regularly. Though long stretches of the Mediterranean coastline are inhospitable for both people and ships, nature bestowed extraordinary favors on a few sites. The northern half of the Mediterranean is relatively benign, marked by abundant natural ports on the mainland and on selected islands. Given these characteristics, it is no wonder that seafarers tended to favor ‘trunk routes’ in the northern half of the sea, where they could move easily from island to island and from port to port. On both the eastbound and the westbound trajectory, ships preferred to follow these trunk routes, where natural conditions presented fewer risks and supported abundant ports and markets.

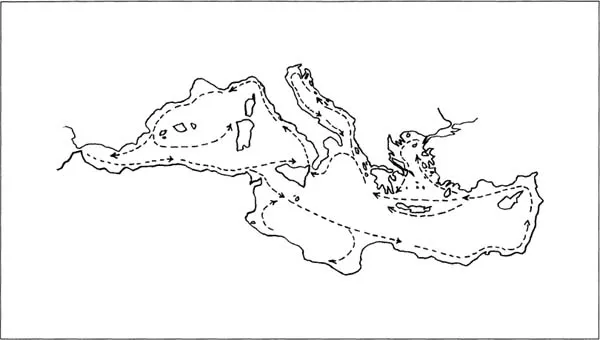

For thousands of years, political and military rivalries focused on a number of key points along the trunk routes in the northern Mediterranean. Whoever controlled enough of those points could determine the terms and conditions of access to the trunk routes, even if they could not monopolize their use. However, if they could keep their lines of communication and supply open, well-entrenched forces could maintain a presence in the heart of alien territory. Nearly all the major battles and sieges in the early modern period were fought over one or another key point along the northern trunk routes.4 Only certain areas of the Mediterranean were appropriate for large sea battles during the age of oar and sail. Nearly all the ideal battle sites are in the northern half of the Mediterranean, and most of them are clustered from Sardinia and Corsica eastward.5 It is no coincidence that the Battle of Actium in 31 BC and the Battle of Preveza in 1538 occurred at virtually the same place in the Ionian Sea. In general, however, major battles were less important in themselves than in their implications for the control of key points along the northern trunk routes.

The physical characteristics of wind, currents, coastlines and ports influenced trade as well as military confrontations. Moreover, in war or peace, the concentrated flow of goods along the trunk routes naturally attracted marauders. Trade and piracy have much in common, and it was not unusual in the early modern period to find the same individuals involved in both seaborne trade and in corsairing, commonly called piracy. Pirates might come from anywhere in the Mediterranean region, and newcomers from northern Europe in the seventeenth century would join in as well. Their attacks might be sanctioned by political authorities or not; they might be carried out by Muslims, Jews, Orthodox Christians, Latin Christians or groups with mixed religious affiliations. It is no exaggeration to say that every great trading people engaged in piracy at some stage in its development, and many of them honed their skills in the Mediterranean.

All these considerations provide the framework for strategic developments in early modern times. The rise of the Ottoman Turks on the western edge of the Muslim world in the fifteenth century set the stage for what would follow, but their advent was part of a much longer process. From the eleventh to the fifteenth century Christian forces dominated both the western and the eastern Mediterranean. Their presence was spawned by the Crusades and maintained by control of key ports and islands such as Zante and Rhodes that linked Crusader enclaves to Christian states in the west. The several Christian powers were rivals as well as natural allies, however, and they often warred against one another as vigorously as they warred against the Muslims. This was particularly true of the rivalry between the Orthodox Christians in the eastern Mediterranean and the Latin Christians in the west.

4. The Mediterranean Sea: sea currents

Gradually, several Muslim polities began to squeeze out the crusader states, but not in a concerted fashion. The Seljuk Turks consolidated their authority in Anatolia in the thirteenth century and ended Christian dominance in the eastern Mediterranean. In its turn, the Seljuk state was reduced by the Mongols to a collection of emirates on the Aegean Sea. By the late thirteenth century pirates from these ghazi emirates of western Asia Minor were attacking shipping in the eastern Mediterranean, and their power grew in the fourteenth century. Rather than acting together to protect Muslim shipping, the emirates took a narrower view, aiming for shortterm gains and relying on outsiders to maintain trade. Christian pirates also preyed on shipping in the area: raiding, collecting tribute and capturing slaves. To lessen the threat of Muslim piracy, Christian merchants from the western Mediterranean made deals with individual emirates and thus diverted the pirates’ attention to the trade of their rivals. A similar pattern of behavior would characterize the seventeenth century as well.

The Ottoman Turks began to unite all of the ghazi emirates in the 1390s, but Tamerlane shattered the Ottoman sultanate into its component parts again in 1402, and it was not until 1426 that the Ottomans under Murad II reconsolidated the emirates into a single state. The Ottomans were willing to make deals with Christian merchants for peaceful trade, but they never abandoned the notion of jihad (holy war) against Christians, which included official raids on Christian possessions (ghawz) and the sponsorship of corsairing against Christian shipping. Before 1453 Ottoman naval actions were generally brief raids rather than concerted campaigns. The Ottomans were fairly new to Mediterranean warfare, but they learned quickly that an amphibious strategy was the best way to achieve control of shipping lanes. They also learned, like others before them, that strategic ports and islands could be used as bases for galley raids on shipping and to control choke-points and collect tribute.6

Scholars have found no documentation for the strategic concerns of the Ottoman sultanate. We learn how they approached naval warfare largely through their actions. Traditional Western scholarship once emphasized the military prowess of the Ottomans and tended to see the sultanate largely as a fighting machine intent on fulfilling medieval prophesies of world conquest in the name of Islam. Relying on ambassadorial reports from Venice and elsewhere, scholars argued that the sultans cared little for commerce, except in so far as it generated tribute payments and restricted commercial activities within their realms. Such arguments portray the Ottoman Empire as the quintessential ‘other’ against which western Europe and its nascent capitalism defined itself.

Modern scholarship paints a different picture.7 We now know that economic, and especially commercial, concerns were an important part of Ottoman strategy. The sultans used their formidable military machine on land and sea to control trade in their sphere of influence, which extended from central Europe to the Indian Ocean, with the eastern Mediterranean as its hub. This strategy evolved in the late fifteenth and the early sixteenth century, as the Ottoman state consolidated its authority. Medieval prophesies of world domination may have inspired the effort, but it was firmly based on existing realities.

Sultan Mahomet II (1451–81) conquered Constantinople in 1453, after several decades of smaller gains. The conquest sent shock waves throughout Christendom, but the Sultan wisely tried to mollify the Orthodox Christians who came under his rule, capitalizing on their fear and distrust of Latin Christendom, which dated from the Crusades. After Constantinople fell, Venice and the Knights Hospitaller of St John, with their stronghold on the island of Rhodes, reinforced and extended their control over a chain of islands in the Aegean. This temporarily blocked the naval expansion of the Ottomans, despite their enormous resources and manpower.

As John H. Pryor has argued, the key to understanding warfare in the eastern Mediterranean in this period is that it was always amphibious, with hit-and-run battles at sea, as attacking fleets aimed for strategic points. ‘When fleet engagements did occur, they did so invariably in the context of amphibious assaults by the forces of one of the two faiths against strategic bases or islands held by the other.’8 For effective defense, the defenders had to prevent the land and sea forces of the attackers from meeting.

The Ottomans captured the island of Lesbos in the Aegean in 1462 and moved westward from Serbia to Bosnia. In response, Venice declared war on Turkey, initiating the first Turco-Venetian War (1463–79). Venice had aimed in earlier times to control the sea, protecting its merchant fleets against depredations and attacking rivals to deny them the use of the favored trunk routes. The Venetians had not aimed at a monopoly of seaborne trade, however. Instead, they captured and held a string of fortified places along the Adriatic, plus Zante, Crete and Cyprus, to use as strategic bases to protect their trade and harass that of their rivals. In the late fifteenth century the Ottomans learned how to defeat the Venetians at their own game. As a result, the Ottomans captured the Negropont (Evvoia) and several trading posts in Morea (Peloponnese).

In what would be his last major campaign, Mahomet II planned simultaneously to drive the Knights Hospitaller of St John from Rhodes and conquer southern Italy. Although the Turks reportedly landed an army of 70,000 on Rhodes (probably an exaggeration), supported by a large galley fleet, they could not dislodge the defending force of 600 knights and 2,000 soldiers, plus the local inhabitants. Formidable fortifications, and the determination of the defenders, thwarted the assault, and the Ottomans withdrew from Italy as well.9 Though the defense of Rhodes was hailed throughout Christendom, and Mahomet II died the following year, the Ottoman advance was merely deferred, not defeated. In between wars, trade by Christian merchants continued in the eastern Mediterranean, protected and taxed by the Ottomans.

5. The Mediterranean Sea, showing location of naval battles, 431 BC to AD 1538

Under Bayazit II (1481–1512), the Ottomans developed a large navy at enormous cost and waged an inconclusive ten-year war with the Mamelukes of Egypt (1481–91). Ottoman galleys also won a major naval engagement against the Venetians in 1499, the first time that the latter had lost a battle since rising to power. For the rest of his reign, Bayazit continued to build the Ottoman Navy. His forces inexorably extended their control of territory and strong points, forcing Venice to recognize that its vulnerability to Ottoman attack had become a fact of life.10 In 1500 Venice had the ‘oldest and largest’ permanent navy in Europe (25–30 galleys), with a small strike force afloat and a reserve force of 50–100 that could be mobilized rapidly.11 None the less, its status among the Christian powers was being eroded by the rising power of Spain in the western Mediterranean and by the expansion of Iberian trade into the Atlantic Ocean and beyond.

In 1415 combined sea and land forces from Portugal captured Ceuta in Morocco, the second Pillar of Hercules (Abyla) in classical mythology. This began a remarkable century in which Iberian mariners and merchants explored and traded along the West African coast and into the eastern Atlantic. In 1486 Bartolomeu Dias of Portugal reached the Cape of Good Hope and in 1498 Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon to Calcutta, pioneering a sea route to India.

Meanwhile, in Spain, the so-called ‘Catholic Monarchs’, Isa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword by Alfred Sant

- Foreword by Paul Kennedy

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I: The Past as Prologue

- Part II: The Mediterranean in the Era of the World Wars

- Part III: The Mediterranean Since 1945

- Part IV: Contemporary Issues in Mediterranean Policy and Strategy

- Notes on Contributors

- Index