![]()

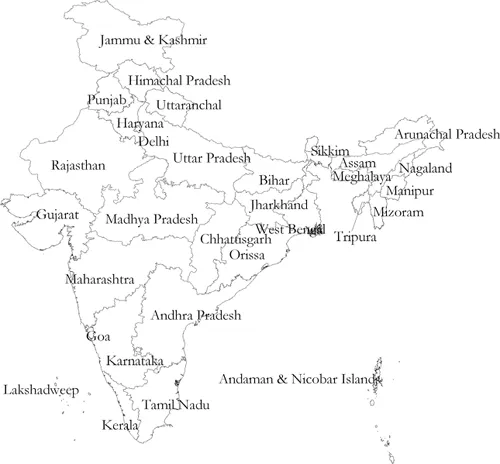

Figure 1.1 State map of India.

Figure 1.2 Map of India with AIDWA membership numbers.

The history of the All India Democratic Women's Association (AIDWA) has richly tangled beginnings that drew from anti-imperialist and anti-colonial movements, land and tenant rights movements, and anti-casteist formations, as well as from the multivalent demands for women's free and equal participation in the social reform movement. Organizationally, its roots develop early in the twentieth century, when women's groups emerged in various regions, states, and localities along different axes of struggle for economic, political, and individual rights and autonomy. Pappa Umanath is one of AIDWA's many founders who came out of the explosive organizing of twentieth-century India. Because she hailed from the southern state of Tamil Nadu, Pappa's vision of AIDWA had a regional specificity, but as an office holder in the organization for many years, she also had a national vision. Her metaphor for the interlocking qualities of the struggles and movements across time and location that developed into AIDWA was the banyan tree. “Like the roots of the banyan tree that spread out as the tree grows, forming many trees that are linked. We formed a national women's organization to fight for the majority of women who face oppression and injustice.” For Pappa, the metaphor of the banyan tree illustrates the regional specificity of AIDWA's national parts. As a national organization, AIDWA joins together state-based women's groups. Some, like the Tamil Nadu Democratic Women's Association (DWA), preceded the national organization by five years or many more. As with the banyan tree, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish AIDWA's distinct branches and their roots from the trees that emerge from those roots. AIDWA is a national organization not in a singular sense, but through the multiplicity of regional formations and regional struggles linked together by their national scope and their common ideological vision for women's freedom and emancipation.

PAPPA UMANATH

Pappa's story of AIDWA's origins weaves together the intersecting movements that shaped her earliest experiences. Her story reveals how these movements nurtured AIDWA's formal inception in 1981 and its growth in subsequent years. Born in 1931, and named Dhanalakshmi, Pappa gained her nickname where she spent the formative years of her childhood—in Ponmalai, a town near Tiruchirappalli in the southern state of Tamil Nadu in a railway housing colony called the Golden Rock Railway Workshop. Early in Pappa's childhood her father died, leaving her family destitute. Pappa moved to Ponmalai with her mother, named Alamelu (but called Lakshmi), and two older siblings to live with her uncle in the railway colony. As a widow, her mother depended upon her kinship ties and her ability to work in order to support her family. Even her ability to work was not always enough, because employment options for widows, regardless of their caste, class, or social status, were very limited.

Pappa's mother, Lakshmi, survived as part of the informal economy dependent on the railway industry, by selling idli snacks to railway workers with the help of her children. Her mother shaped her anti-imperialist political commitments to her work's mobility and participated in the freedommovement as a messenger. Pappa described her mother's influence on her own activism with due pride:

Some [women] were involved in guerilla struggles, satyagraha [Gandhian national independence campaigns], going to jail. After Independence we fought so that white men's actions would not be repeated. We had to fight against the incoming Congress Party. My mother was not literate, but she taught me to be sensitive to the political issues of the day. During the underground days of the Party [Communist Party of India, or CPI], she safeguarded Party letters. She hid the letters in her hair and carried a basket on her head. She could never read the contents of the letters because she was illiterate. Her job was to deliver the letters, to meet Party members secretly, and to deliver food to them so the British authorities would not detect them. I am proud of my mother's work against the British and my own work against imperial rule.1

Lakshmi's radicalism in the larger context of the railway workers' militancy both before and after India's independence informed Pappa from an early age. She recounted her memories of one critical struggle by railway workers for the South Indian Railways (S.I.R.) to gain fair wages and working conditions through organizing a union, an act declared illegal by the British colonial authorities.

The watershed struggle began in May 1946, and followed immediately with retribution against union organizers by the general manager of the railway, J.F.C. Reynolds.2 Railway employees held a one-day strike to protest the dismissal of workers who were organizing for the union. Following the strike, the administration reduced workers' wages and limited their rights to investigate unfair dismissals. The S.I.R. railway workers dug in their heels. By July, five thousand workers struck to reinstate the fired workers who were dismissed for carrying out trade union work. Support meetings in the evenings during the strike brought a surge of support from the larger community, with twelve thousand people attending the meetings. Over the following months the strike continued, gaining even more solidarity across the region and inspiring new hopes for anti-colonial and workers' movements throughout the country. In response, the Malabar Special Police force was contracted to decimate the S.I.R. strike.3 On September 5, 1946, they opened fire on the crowd, shot seven people and killed two, one of whom was a local Ponmalai communist activist in the volunteer corps of the Golden Rock railway union. After the firing, the police ransacked the railway colony, beating the workers' family members, including women, girls, and boys. Four more people were killed in the raid. The violent recklessness of the railway company's actions and the police force's brutal murder of a comrade and other railway workers had profound effects on Pappa and her family and on the militancy of the entire railway colony.

The story of the Golden Rock railway workers' determination and police repression ricocheted through railway colonies across the country as the police sought to curb railway workers' militancy through violence. Yet the death of activists only further galvanized the self-consciously working class movement among railway workers.4 Railway workers' union activism was not confined to discrete issues of wages or job security but formed a network for sustained working class opposition to British rule during the early twentieth century.5 This network crossed regions and states alongside the tracks of the railway to form an opposition that included all members of the railway workers' families as well as the families in the subsidiary industries that relied on the railway, such as Lakshmi's food business. Pappa mentions radical women's involvement in guerilla actions that included armed struggle, satyagraha actions guided by Gandhian non-violence tenets, and courting arrest as the militant actions chosen by women to resist British imperialism. Another tactic that Pappa alludes to in her narrative, but doesn't explicitly name, is labor strikes. The centrality of the railway to the British imperial project and revenue, together with its systematic exploitation of railway workers, created a volatile locus for political resistance to the Raj. Union members debated tactics such as non-violent satyagraha alongside a railway workers' strike, the method the union ultimately chose to pursue in the Southern Mahratta Railway Strike of 1932–1933.6

The Communist Party of India (CPI) provided important linkages between the residentially based alliance between the railway's industrial working class and the railway's informal economy, made up of people like Pappa's mother Lakshmi. When it formed in 1945, Pappa joined the radical children's group, called the Balar Sangam, which had integral connections to the CPI. She was twelve years old. In 1948, when Pappa was fifteen, Lakshmi helped to organize women in the railway colony into the Ponmalai Women's Association (PWA), another primarily neighborhood organization linked to the CPI. The association functioned in part as a women's committee of the union, to support union strikes and to fight against police and company sanctions that targeted politically active workers.7 But the association also included the many women without direct ties to the union who lived in the neighborhoods of the Golden Rock railway colony. Pappa also joined this group immediately. Because it linked women where they lived as much if not more than where they worked, the PWA addressed more than women's issues within the workplace. It also contested oppressive matrimonial practices, such as child marriage, and fought domestic violence among residents in the railway's housing colony.

Many of the PWA's issues in 1948 mirrored the work by progressive, often communist women in the national women's organization, the All India Women's Conference (AIWC). During this same time, the progressive forces within AIWA sought to rewrite the Hindu Code Bill to provide women the right to inheritance, property, and divorce.8 The PWA was an organization in its own right, connected to the labor union movement and the CPI, but not a “wing” of either. The PWA was based in the neighborhood of the Golden Rock railway colony and brought women together from across the railway colony to fight for women's issues that might have otherwise been marginalized as secondary or tertiary issues in the union or the CPI. With its focus on women's lives as well as their work, the group sought to build leadership among all women, rather than concentrating primarily on waged women workers.

Pappa described her own childhood reactions to patriarchal control in this context:

I was a small girl at the time. Everyone in our colony was a member [of the PWA]. She [her mother, Lakshmi] began to challenge matrimonial issues and atrocities against women. I hate male chauvinism. Even as a small girl I would ask why women are held in low esteem. Only with that anger can we build a women's organization. Why shouldn't women raise their voices against beating wives? All women are against this. My mother fought against this violence in her time.9

The basis for women's organizing, in Pappa's terms, begins with the indignation and raw anger against women's subordinate status in relation to men. The strength of the women's movement relies on the impetus of this refusal to accept patriarchal norms and social customs, and needs an independent basis to sustain the power of this rejection. The railway union of her colony and the CPI supported the Balar Sangam and the formation of the PWA as kindred political formations that brought more people into the larger goals of their struggle for rights, independence, and freedom. Women's and youth groups operated within the locality of Ponmalai's railway housing colony and alongside (although not wholly within) the national political organizations of the railway workers' union and the CPI. To describe these relationships in current terms, the Balar Sangam functioned as a mass organization that developed youth leaders and built support for a union led by communists or people closely allied to the Communist Party. The PWA had components of a union women's committee, in its overt linkages to the railway workers' union, and of the mass organization, as it sought to organize all women in the locality around a range of women's issues, like violence and child marriage. Communists and mass movement activists like Lakshmi and Pappa were outside of the formal, waged economy, a location almost certainly not unionized. Their activism created integral linkages between unionized and non-unionized workers in their locality of the railway colony, as well as between the CPI and allied mass organizations. They also provided a valuable spur to remind the union and the CPI of women's issues as workers and their oppression under patriarchy that demanded specific demands and campaigns to address.

In 1943, the same year Pappa joined the Balar Sangam, she also courted arrest by joining a non-cooperation movement procession against the British occupation of India.10 She described her own individual and collective aspirations many years later. “The judge asked me why I joined the non-cooperation movement. I said, ‘To wipe you all out.’ The judge asked, ‘Can you?’ I replied, ‘Yes, I can. That is why I am here.’”11 Pappa told of her disappointment when the judge refused to jail her for her activities due to her young age. “I cried as I lay on my mother's lap. My mother comforted me, saying, ‘That's okay if you could not go this time, you can go another time.’ She gave me courage. My mother was illiterate, and her words surprised me.”12

ORAL HISTORY AND POLITICAL ORGANIZATION

Pappa told me the story of her mother nurturing her own revolutionary resolve with practiced ease and good humor, although with a disciplined focus. These were all stories she was comfortable recounting. We met only once, in 2006, months into my stay in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, where I researched AIDWA's organizing campaigns as well as their cadre training methods, spending much of my time in the neighborhoods of North Chennai, among AIDWA members who depended on the fishing industry for their livelihood. For most of my research I worked alongside B. Padma, a former member of AIDWA, who translated my questions into Tamil and the women's answers from Tamil into English. Soon after the interviews, we would comb through the group and individual interview tapes together, sharpening these quick translations into more nuanced responses. Often, I would then return and interview AIDWA members again after going over the interview tapes. I had only one opportunity to meet and listen to Pappa Umanath's story. My questions were almost exclusively about origins, of AIDWA and her own family's three generations in the Indian Communist Party. I have woven her story of her life and AIDWA's formation into this chapter, along the grain of, although not always exactly replicating, her chronology and her information. Many of her anecdotes are supported by existing historical accounts, such as her remembrance of Tania, the Russian anti-fascist fighter during World War II.13 Some retell dominant stories of progressive Indian movements from an unfamiliar perspective.

Oral autobiographical histories are often discounted for chronological inaccuracy and the faulty cracks of memory; yet these same qualities reveal important facets of gendered subjectivity, class, and power.14 Much can be gleaned from their structure, as well as the emotional, allegorical, and factual meanings that narrators and researchers ask these stories to convey. Those narratives that uphold existing relations of power exist more comfortably in the public domain. Memories, like Pappa's, that challenge accepted truths and power are transmitted from a location that oral historians have described as “the interstices of society, from the boundaries between the public and the private.”15 Pappa recounted a multi-layered story about intergenerational struggle passed from her mother to herself as her mother's daughter; yet, she did not tell me how she had passed her revolutionary commitments to her own politically active daughters. She told me a story of being taught (not of teaching) resolve in the face of seemingly impenetrable colonial, and later post-colonial, authority. She told this story in Tamil to me, a foreign researcher who speaks no Tamil, through a translator, Padma, whom she had met several times befor...