eBook - ePub

Turkish

About this book

Turkish is spoken by about fifty million people in Turkey and is the co-official language of Cyprus. Whilst Turkish has a number of properties that are similar to those of other Turkic languages, it has distinct and interesting characteristics which are given full coverage in this book. Jaklin Kornfilt provides a wealth of examples drawn from different levels of vocabulary: contemporary and old, official and colloquial. They are accompanied by a detailed grammatical analysis and English translation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. Syntax

1.1. GENERAL PROPERTIES

1.1.1. Sentence types

1.1.1.1. Direct speech versus indirect speech

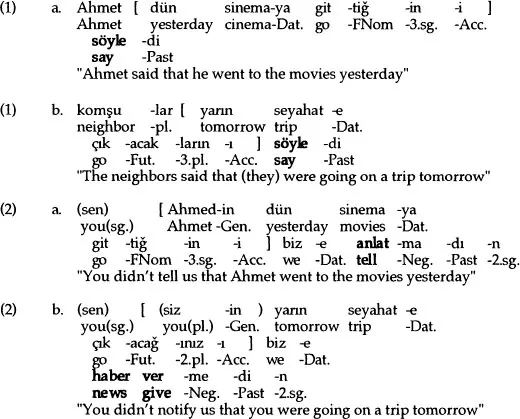

Indirect speech in Turkish is represented in the form of a nominalized clause (as are most constituent clauses) and is introduced by a variety of verbs of saying, e.g. söyle ‘say’, anlat ‘tell’, haber ver ‘notify’:

Since we shall discuss the properties of embedded clauses later in more detail, let us point out the main properties of the constituent clauses in the examples above: the subject of the embedded clause bears genitive case, the nominalized embedded verb exhibits nominal (rather than purely verbal) subject agreement markers (see sections 2.1.3.6.2.1. and 2.1.3.6.6.5.), and the whole embedded clause is marked with accusative case, since the clause is the direct object of the matrix verb.

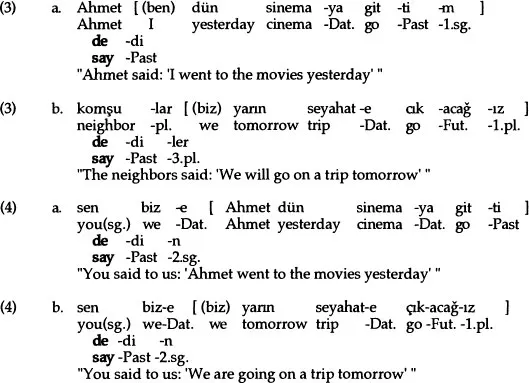

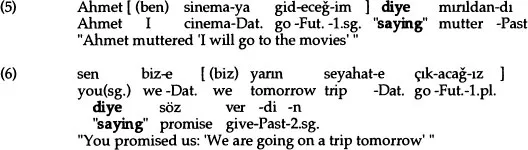

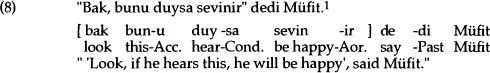

Embedded clauses expressing direct speech, on the other hand, are not nominalized and have all the properties of a fully finite simple or matrix clause: the embedded subject is in the nominative case; the embedded verb can bear all tense and aspect distinctions and carries subject agreement markers of the verbal paradigm; such direct speech is introduced by the matrix verb de ‘say’ in a variety of tense and aspect forms:

When direct speech is followed by a finite verb other than de, the particle diye (originally an adverb derived from the verb de) must follow the quotation:

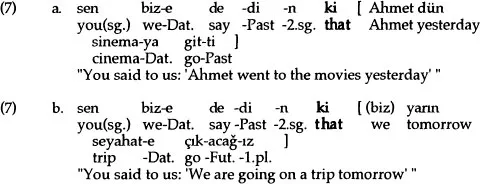

Yet another type of directly quoted speech makes use of a syntactic pattern borrowed from Persian and used for subordination in general. The subordinated clause—here, the direct speech—is introduced by the subordination marker ki ‘that’:

One further difference between indirect and direct speech is word order. The nominalized clause representing indirect speech can be placed anywhere in the sentence (although the basic position of that clause is to the immediate left of the matrix verb, as are all direct objects); in this respect, such clauses behave the same way as all other types of (morphologically Case-marked) noun phrases and nominalized clauses, as will be seen later on. The fully finite, non-nominalized clauses representing direct speech, however, may occur only to the immediate left of the matrix verb de; in other words, these “direct speech clauses” may not move away from their basic position, and nothing may intervene between them and the matrix verb (with the exception of a highly limited number of particles—e.g. the Yes/No question marker mI, the conjunction marker DA).

Yet another difference between indirect and direct speech is pragmatically based and not Turkish-specific, having to do with the person feature of the embedded subject. Depending on the person of the speaker and/or addressee of the matrix utterance, the subject of the direct speech will change its person feature in quoted speech, in ways familiar from English and illustrated by the examples above.

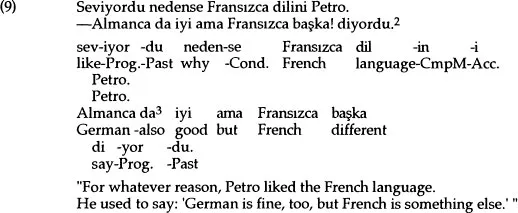

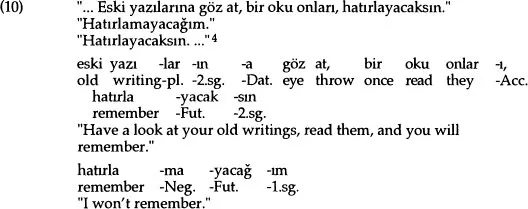

In the orthography, direct speech is marked in two ways: either by quotation marks within the main sentence, or in a new line, preceded by a dash. Here are some examples from the literature:

Note that, as in English, the quotation can (but doesn’t have to) precede everything else in the sentence, which has the effect of forcing the subject to postpose to a position after the verb.

Note that with the second orthographic convention for quoted speech, i.e. where a dash is used to introduce the quotation, the following part of the main sentence is not set off visibly from the end of the quotation.

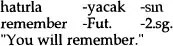

Finally, it is worth noting that where a lengthy dialogue of quoted speech is rendered in a text, not all utterances have to be marked by a form of the verb of saying. There can be pages of dialogue, where each utterance is marked only by one of the orthographic conventions, and where no material of the frame intervenes; here is an example of a short dialogue of this sort:

1.1.1.2. Different types of interrogative sentences

1.1.1.2.1. Yes/No questions

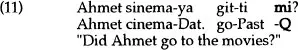

Yes/No questions are formed by attaching the particle mI; this morpheme gets cliticized to the predicate of the sentence and then has the whole sentence in its scope:

We shall see later, in section 1.11., that the same particle can also attach to a smaller constituent, thus taking only that constituent into its scope and focusing on it.

The Yes/No question particle has been traditionally called a postclitic, for the following reasons: on the one hand, it clearly forms a phonological word with the stem it attaches to, since it undergoes word-level phonological rules like Vowel Harmony in accordance with the stem. On the other hand, while stress in Turkish is usually word-final, this particle is never stressed; rather, it “throws back”, as it were, stress to the preceding syllable, thus behaving as though it were outside the word boundary.5 As shown in (11), the standard orthographic convention is to write the particle separately from the preceding stem (predicate or constituent), in spite of the fact that phonologically, it is part of the same word.

The position of the Yes/No question particle is after the tense suffix and before the (subject) agreement marker; however, if the verb is in the definite past, the particle will follow rather than precede the agreement marker. The following examples illustrate the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Editorial Statement

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- List of abbreviations

- 1 Syntax

- 2 Morphology

- 3 Phonology

- 4 Ideophones and interjections

- 5 Lexicon

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Turkish by Jaklin Kornfilt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.