![]()

1 Introduction

A Conceptual Overview

Susan M. Walcott and Corey Johnson

The term “Eurasia” almost invariably invokes images of geopolitical intrigue and even primordial human struggle. In his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four George Orwell (1949) referred to the neo-Bolshevik superstate in control of Europe and northern Asia as a metageographical “Eurasia,” one of three constantly contesting power blocs. In popular modern usage, Eurasia is often accompanied by discussions of a “Great Game,” “a chessboard,” and civilizational chasms (Brzezinski 1997; Kaplan 2009). Such depictions of Eurasia became more prevalent following the breakup of the Soviet Union and the growing regional influence of China and India. Many social scientists use the term uncritically to denote a field of ethnic, political, or economic conflict, the big territorial Space in which old-fashioned confrontations occur (e.g. Freire and Kanet 2010). These connotations are related in no small part to the region’s place in past imperial power struggles, and an overwhelming sense that “geography is destiny” in the spaces between the major powers on the globe’s largest landmass (Kaplan 2009). In this regressive perspective, China and the U.S. replace Russia and Great Britain as contending geopolitical “chess” strategists, with intervening interests such as nuclear India and Pakistan along with semi-resurgent Russia.

Portrayals of this type obscure the fact that connectivity, as well as conflict, characterize Eurasia now and throughout most of history. It would be naïve to discount negative uses of “Eurasia,” because the term evolved in particular historical and geographical contexts. The terms Eurasia and Eurasianism continue to be influential in Russia and the orbit of the former Soviet Union as geostrategic philosophies that recall Mackinderian classical geopolitics concerned with the influence of the great center of a bi-continental landmass (Morozova 2009; Senderov 2009; Laruelle 2008; Shlapentokh 2007). The founder of British geopolitics saw countries contending for natural resources at the heart of Eurasia, even prior to the age of petroleum, transportation routes, and trading centers. His boundary of the “pivot area” ran from the Caspian Sea to western China’s arid Taklimakan desert, now distinguished by the mummified remains of Celtic-type post-glacial melt migrants in western China between Mongolia and Tibet (Barber 2000). Swanstrom (2005) extends Eurasia from its Central Asian heartland pivot east to China, following movements of natural resources through pipelines and trans-Islamic terrorists. Multiple interdependencies bind the region’s interests, from the shared prosperity inducement of trade to military power projection—underlined by the fear that conflict may lead to the termination of economically essential access to markets (Norling and Swanstrom 2007).

Much like the term “geopolitics,” Eurasia bears the baggage of prior eras of state-centered hegemonic misuse, imperialist hubris, and intermittent ignorance by Western powers (O Tuathail 1985; Lewis and Wigen 1997). Boundaries of this region can now be distinguished by separate blocs of allied, largely contiguous nations, from the European Union on the west to organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization on the east (also known as the “Shanghai Five” for the number of its core members). Regional blocs as well as national borders assert pressure on the frontiers (Walters 2004). Geostrategies to manage frontier border issues include working through networks and colonial borders, invoking real and imagined relationships as ways of territorializing space. In some functional sense frontiers are “fuzzy” rather than firm lines, depending on political assertions and invocations of sovereignty or advantage to stretch their power zones past spaces formally delineated as borders, encompassing considerations of groups in one territory working on behalf of or sharing the goals of a core within another territory.

The simple question informing the idea for this book asks: What should the regional term “Eurasia” include, and on what basis? We find it worth noting that the origins of the term in natural science were about the geologic and biogeographic unity of the world’s largest landmass, yet it is used far more commonly today as shorthand for Central Asia. Few Europeans or Asians would consider themselves residents of the region “Eurasia.” Furthermore, few geographic terms are used quite so loosely with respect to a delimitation of where a place actually lies than Eurasia, as if it is either self-evident or irrelevant. Finally, qualitatively the geographic moniker Eurasia is most commonly used in regressive, throwback contexts. When writing of the incorporation of China or Vietnam into a deeply interpenetrated 21st century global economy, “Asia” or some regional variant thereof suffices, whereas power plays around natural resources or military strategy is more likely to take place in a “Eurasian” context. Why is this? Is the term worth salvaging?

We propose that it is time for rethinking the regional concept of “Eurasia” as a scale of analysis and as a geographical place. This edited volume is motivated by the relative neglect of economic, cultural, and political interactions at the analytical scale of Eurasia, and by our belief that current debates assume that Eurasia is merely a catchall term for bare ambition and geostrategic wrangling. Taken together, the contributions to this edited volume argue that what unites Eurasian space is at least as important as what divides it. We hope this edited volume will provide a set of possibilities for imagining a new functional regional conceptualization. We explore this by examining dynamic geopolitical and geo-economic links reconfiguring Eurasian spaces from the eastern edge of Europe through the western edge of Asia. The framework of this book considers borders not simply as barriers but as zones of political and economic transfer, and sites where mutual interests as well as contestation become most apparent. Understanding Eurasian geography requires understanding the nature of three basic notions: (1) We are dealing with a highly contested term that must be unpacked; (2) however geographically defined, Eurasia is a dynamic space where interests overlap and therefore give rise to conflict at multiple scales; and (3) Eurasia, as the earth’s largest landmass, represents historically and presently a zone of interconnectivity. It is this last notion that in our view previous treatments most neglected.

WHERE IS EURASIA? ORIGINS OF A CONTESTED TERM

In common usage, the term “Eurasia” often functions as a surrogate term for Central Asia, which is curious when one considers its origins. The Austrian geologist Eduard Süss used the term Eurasia in the late 19th century in order to challenge the then dominant cultural conceptualization, dating to the ancient Greeks, that Europe and Asia were two different world realms. He argued, instead, that Europe and Asia, at least geologically and zoogeographically speaking, belonged together (Kaiser 2004). Not long thereafter, following the geopolitical upheavals in the wake of World War I, a group of exiled Russian intellectuals—mainly linguists and geographers—based in Sofia, Prague, Paris, and Vienna made a political project out of “Eurasianism.” This viewpoint rejected Eurocentric conceptions of “universal” cultural values, and replaced it with Slavocentrism. Russia, in particular, stood at the cultural and geographic heart of the world’s largest landmass. As such, Russia had a special, hegemonic role in shaping affairs there and served as a bridge between West and East. In the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, this brand of Eurasianism has re-emerged in Russian political discourse (Bassin 1991; Senderov 2009; Morozova 2009). Counter perspectives to this also emerged, such as the notion that Eurasia no longer exists in the sense of a “natural” habitus for Russia’s geopolitical ambition, so it must choose between regressive regional ambition and a place in the increasingly globalized economy dominated by the West and East Asia (Trenin 2002).

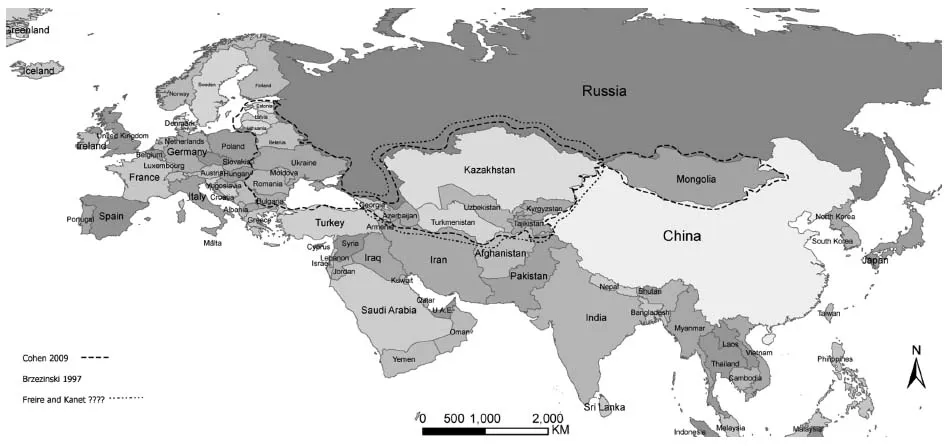

The common mental map of “Eurasia” therefore reflects the places that were most involved in past hegemonic struggles over the core of the large Eurasian landmass. These struggles took place primarily between European powers and Russia during the 19th and 20th centuries. They involved territorial struggles, ideological struggles (in the case of the Cold War), and resource struggles (the prize of Caspian oil, for example), and shared a common element of geopolitical wrangling between the (then) greatest world powers. The recent resurgence of Great Game geopolitics, with India, China, and others now key pieces on the metaphorical chessboard, employs similar language to that earlier period, even though the strategic interests and key players have shifted quite dramatically in the intervening century. No generally accepted map or concept of Eurasia exists, and a variety of texts portray various boundaries (see Figure 1.1). In diplomatic fashion, the U.S. Department of State merely conflates into one Bureau all of western and eastern Europe from Portugal to Azerbaijan.

Figure 1.1 Various boundaries previously proposed for Eurasia, including Central Asia, CIS, and former Soviet satellites (Brzezinski 1997, Pavlakovich, et al. 2004, U.S. Department of State 2011, Authors).

Curiously, the constituent parts of Eurasia about which we teach in classes and see depicted on the news do not carry the same politically negative, conflict zone connotations: “East Asia” and “Central Asia” denote Eurocentric place markers, regional categories into which we lump many characteristics, but which do not carry the same baggage of Eurasia. One might expect the larger spatial scale of Eurasia to possess more positive associations, because it encompasses more area, but instead the opposite is true. The smaller-scale regional divisions from typical World Regional Geography textbooks or specialty group names in different academic disciplines evolved in the imaginations of mainly Western observers. We now take for granted that East, So...