- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1976, this book deals with contemporary tensions between the West and the Third World, caused by hunger, malnutrition and poverty, perpetuated by an imbalance in the distribution of world resources. The book deals with the issue of malnutrition in the Third World, which owes much more to poverty and unemployment than to agricultural failure. The author also believes that population control can do little in the absence of a more equitable distribution of world resources and political power within and between countries involving a fundamental change in ideology and education.

This is a challenging and critical book, whose arguments cannot be ignored by anyone concerned with the creation of a just and stable world order.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Food and Poverty by Radha Sinha in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Agribusiness. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Nature of the World Food Problem

The popular conception of the world food problem as a race between population growth and food supply is too simplistic. It also diverts attention from more relevant issues. In its simplest form the argument is that increases in food production in the developing countries have either been outstripped by unprecedented rates of population growth or, at best, have barely kept pace with them. It is also believed that the carrying capacity of the spaceship Earth has nearly been reached; little potential for increasing production exists. The inevitable conclusion is that many developing countries will be frequented by catastrophic famines in the very near future. As a result of widespread crop failures in the early seventies such alarming prophecies have become more common.

Admittedly, the incidence of hunger and malnutrition1 is relatively high in densely populated countries, but as will be shown later, this is related not so much to population growth as to the unequal access to land, and other sources of wealth and income in these countries.2

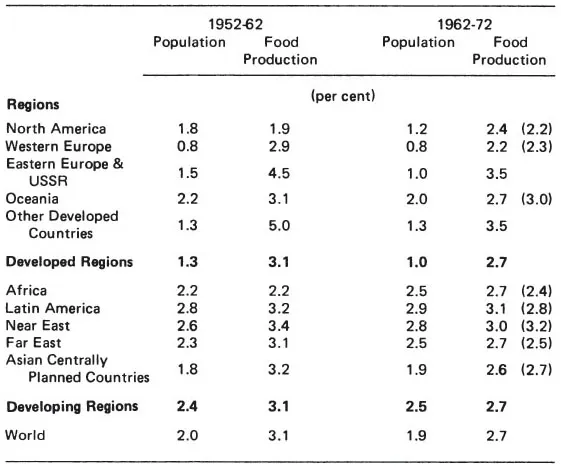

In a study of the world food problem, prepared by the FAO for the World Population Conference (1974), it has been shown (see Table 1) that at the world level the rate of growth of food production substantially exceeded population growth throughout the 1950s and 1960s.3 In both decades, population grew at around 2 per cent per annum, while food production in the 1950s increased annually by about 3.1 per cent, slowing down to 2.7 per cent per annum in the 1960s.4 The rate of increase of food production was much the same in both the developed and developing countries. However, population increases in the developed countries continued at around 1 per cent per annum as against 2.5 per cent per annum in the developing countries.5 This high rate of growth of population in the developing countries was mainly the result of the successful introduction and growing acceptability of modern medicine, and the application of new ideas in public health and sanitation.

Table 1. Annual rates of growth of population and food production

Based on FAO (1975), Population, Food Supply and Agricultural Development, Table 1, p. 2. The figures in brackets represent the growth rates between 1962 and 1974 for regions where the inclusion of 1973 and 1974 changes the trend rate of growth. Since the early 1970s were years of poor harvests in various parts of the world, the overall rates of growth of food production between 1962–74 barely kept pace with population growth in the Far East and, in fact, were slightly lower than population growth in Africa and Latin America.

Thus the unprecedented rate of population growth which has been experienced by the developing world is itself partly a sign of the success of developmental efforts and not of failure. Undoubtedly, huge increases in population over short periods have created serious problems for some densely populated countries, particularly in their efforts to accelerate the pace of economic development; the safety valve of migration, which was commonly available (and still is, though on a more limited scale) to the European countries in their early stages of development, is not available to them. But in many countries population densities are still low and an increase in numbers may often assist such countries in fully developing their resources. After all, the development of North and South America, South Africa, and Australasia owes a great deal to population increase.

It is undeniable, however, that some countries, particularly Asian countries such as China, India and Bangladesh, have serious population problems. Nor would their problems really be greatly ameliorated if possibilities of migration were open to them; even at a much reduced rate of growth the annual additions to total population would be staggering. The leaders of these countries are well aware of the seriousness of the problem.6 India was one of the first countries in the world to adopt population control as an official policy although, largely for social and psychological reasons, it has not achieved any appreciable success. China, in spite of its anti-Malthusian Marxist thinking, has now adopted population limitation as a major part of its development policy. There are already some hopeful signs. In several developing countries the age at marriage, particularly for girls, has gone up. There has also been some fertility decline among mothers in the younger age groups; and there have been some changes in attitude to family size. These tendencies will certainly gain momentum with the increasing education and employment of women.

There is a definite double standard in the development literature on issues of population and food. While the ‘unprecedented’ rates of population growth have been underlined ad nauseam, the similarly unprecedented rates of growth of food production in developing countries have rarely received even a casual mention. FAO figures indicate that between 1961 and 1974 at least 31 out of 101 developing countries attained a rate of growth of food production of over 3.5 per cent per annum, a rate attained by only 5 developed countries (out of 34) during the same period, while in another 26 developing countries food production increased by between 2.6 and 3.5 per cent per annum. In terms of historical experience such growth rates are unmatched. Even the much-talked-of high rates of growth of agricultural output in Japan after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 did not exceed 2 per cent per annum. There is still some controversy as to whether the actual rate was much more than 1 per cent but earlier estimates of a 3 per cent growth rate have now been scaled down to 2 per cent.7

During the last two decades (1952–72) food production failed to keep pace with population growth in over a third of the developing countries. However, these countries account for only 14 per cent of the total population of the developing countries. Besides, many of these countries are producers of petroleum (e.g. Iraq and Indonesia) or cash crops such as sugar (e.g. Mauritius). Under the circumstances, the increasing incidence of hunger and malnutrition in developing countries cannot be explained wholly in terms of the failure of agriculture to keep pace with population growth.

Increasing imports of food

Of course, increased agricultural production and the consequent increase in incomes in the rural areas has led to an increased demand for retaining domestically produced food and this, in turn, has resulted in a slow rate of growth of the marketed food surplus transferred to the urban areas, and at a time when urban income and population have been growing faster than in rural areas. Consequently, there has been an increasing demand for imports of food,8 particularly food grains, in several developing countries. However the developed countries import much more food and are more dependent on food imports9 than the developing countries. Japan, the United Kingdom, Italy and West Germany are the largest importers of food grains; between 1970 and 1974 their net imports of cereals amounted to 37 million tons per annum, with their combined population of only 300 million people. As against this, the two largest developing countries, China and India, with almost 1,300 million people imported only about 9 million tons even though this period was one of poor harvests for both countries. During the same period, on average the food deficit richer countries imported (net) 48 million tons of cereals annually as against only 29 million tons imported by the developing countries. The fact that the food importing developed countries import much more on a per capita basis and are far more dependent on imports than the developing countries has escaped public notice mainly because countries are generally classified into two groups, developed and developing; and not food surplus and food deficit countries.

Current availability of food

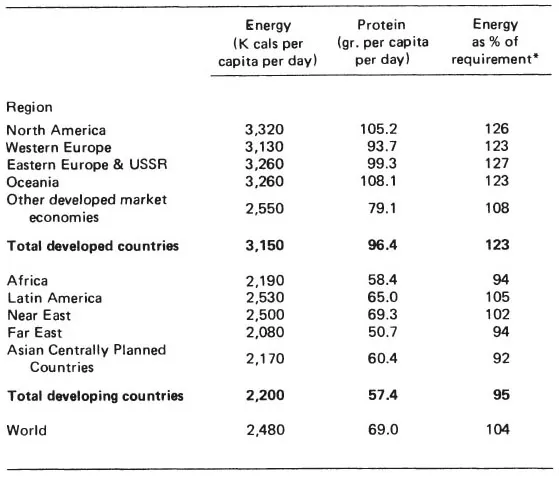

According to recent UN estimates per capita food availability at the world level in 1969–71 (average) was at least 4 per cent more than the requirement (see Table 2), despite the fact that some major grain surplus countries, the USA, Canada, and Australia,10 were subsidising their farmers to leave some of their land uncultivated. The total area of this land in 1970 was around 40 million hectares. Since on average the developed countries were producing 3 tons of cereal per hectare, the land withdrawn from cultivation could have represented a loss of as much as 120 million tons, equivalent to 10 per cent of the total world output of cereals.

Table 2. Average energy and protein supply,* by region (1969–71)

Source: UN World Food Conference (1974), Assessment of The World Food Situation (mimeo.), Table 9, p. 58 (henceforth Assessment).

* The figures relate to protein and energy content of the food available at the retail level after making allowance for storage and marketing losses and waste.

The average energy intake in the developed countries during 1969–71 was 23 per cent more than the requirement,11 while that in the developing countries was 5 per cent less than the requirement. The deficiency in the Far East (including the centrally planned economies) and Africa varied between 6 and 8 per cent. On a world level the protein situation was more satisfactory than is usually thought. According to the currently prevailing views on nutrition 40 to 50 grammes of protein per capita per day is quite adequate for an adult. On this standard the developed regions have been eating twice as much (or even more) than they require. Even the developing regions seem to have enough protein on average levels of intake. But in those cases where the intake of energy is less than the requirement, some of the protein is used up in meeting the energy gap.12 As such it is not easy to say whether the intake of protein in these countries is adequate, even though the figures may indicate this.

Thus it is not an overall shortage at the global level that accounts for the widespread hunger and malnutrition. A recent US Department of Agriculture Report13 has suggested that if only 2 per cent of the average annual world cereal production during the last decade were assured to the malnourished in addition to what they already get, much of the malnutrition in the world would be eliminated. Thus the amount of grain needed to eliminate the worst aspects of malnutrition would not be more than twice the quantities moved under various food aid programmes during the 1960s.14 Therefore the explanation for the persistence of widespread hunger and malnutrition lies largely in the fact that the poor (countries or people), for lack of purchasing power, are unable to meet their basic human needs, while the rich continue to carve up the lion’s share of the world’s food resources. The average person in a developed country consumes nearly three times as much sugar, more than four times as much meat, fats and oils, and about six times as much milk and eggs as the average person in a developing country.15 Such disparities are not so obvious if the average calorie intake of the rich and poor countries is compared. As can be seen from Table 2 the average daily calorie intake in the developed regions in 1969–71 was around 3,150 as against only 2,200 in the developing regions. The respective intakes of protein were 96 and 57 grammes. Both the energy and protein intakes in the developed regions were well in excess of requirements. However, such aggregates do not provide a meaningful comparison of the qualitative differences in the levels of food consumption between rich and poor countries. Over two-thirds of the protein consumed by the richer countries comes from animal sources, while it is plant foods which supply three-quarters or more of the protein in the diets of the populations of the poor countries. This is reflected in the fact that the average cereal consumption (taken directly, as well as animal feed for production of meat etc.) of a person from the developing countries is nearly half a kilo per day; for the developed countries as a whole it is three times as much. However, for the USA and Canada it is a little more than five times as much.16

A lot of cereal production in the developed regions is used for the production of meat, milk and eggs. The amount of grain used for animal feed alone in the richer countries is around 370 million tons per annum, which is roughly equal to the total amount of cereal consumed by China and India together.17 Although most nutritionists have been suggesting that animal products are not essential for a healthy diet (though they may be desirable within certain limits) increasing attention is being paid to the expansion of the livestock sector, not only in developed countries, but also in some developing countries, sometimes supported by international agencies such as the World Bank, involving a considerable diversion of grains to animal feed, and at a time when increasing numbers of people are being added to the millions already underfed. In poorer countries cereals must receive precedence because in situations ‘when intakes of both energy and protein are grossly inadequate, the provision of protein concentrates or protein-rich food of animal origin may be a costly and inefficient way of improving the diets, since energy can generally be provided more cheaply than protein of good quality’.18

There is a growing recognition of the ‘unfairness’ in the present use of world resources between countries and it is being suggested that the richer countries should accept a voluntary ‘cut’ in their levels of consumption of food and other scarce resources.19 A trend towards reduced consumption of animal fats for medical reasons is already underway. Between 1940 and 1971 the average American has reduced his consumption of butter from 17 lb. per annum to only 5 lb., while there has been an increase in the consumption of margarine from 2 to 11 lb. Lard has already been replaced by vegetable shortenings. Non-dairy whipped toppings and ‘whiteners’ are already replacing those of dairy origin.20 Similarly, attempts are being made to substitute high-quality vegetable protein for animal protein.

It is still uncertain whether voluntary efforts directed towards reduced consumption of animal products will ever attain more than a marginal significance. Even if they do, it is difficult to visualise resources released by such efforts becoming easily accessible to the needy without a radical rethinking on the issue of a more equitable distribution of world resources between countries and wit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Nature of the World Food Problem

- 2. Increasing Food Production

- 3. Choice of Technique: Walking on Two Legs

- 4. Employment Creation: The Planners’ Achilles Heel

- 5. Land Reform and the Poor

- 6. Credit, Marketing and Price Policy

- 7. Need for New Ideology

- 8. World Trade and the Developing Countries

- 9. Development Assistance and the Poor

- 10. Inevitability of Confrontation

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index