![]()

Part I

Mapping Higher Education

![]()

1 Higher Education and Emerging Markets

Opportunity, Anxiety, and Unintended Consequences amid Globalization1

Peter Marber

This chapter examines the recent evolution and expansion of higher education in developing countries during an unprecedented wave of economic and social globalization since the mid-1980s. While many upsides exist with increased higher education rates, such potential is matched by rising nervousness from students, parents, governments, and schools everywhere. These developments mirror the opportunities and anxieties of economic globalization. Given the early stage of this higher education expansion, there may be unintended consequences—both negative and positive—that unfold in the 21st century.

OVERVIEW

During the last century, mass primary and secondary education has created an extraordinary explosion in human capital and output, most recently in the developing countries of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. Unsurprisingly, this has led to a dramatic expansion of higher education globally from 1900 to 2000, with student enrollments mushrooming some 200-fold (Schofer and Meyer, 2005). Such education-based talent is generally accepted as essential in economic growth (Lucas, 1988; Barro, 1991), and this trend also has roots in sociological theories arguing that developing human capital through education—properly supported by government—can lead to unlimited societal progress. Further, increased higher education is believed by many to be inextricably linked to greater demands for democracy and human rights, the rise of national socioeconomic planning, and the expansion of science as a broader authority in most societies (Schofer and Meyer, 2005).

It is no coincidence that rising formal education has paralleled the expanding global economy, particularly since the late 1980s. World supply chains have been built upon more capable workers, new information and communication technologies, and pro-market philosophies that have engaged more countries and people in producing more goods and services than ever before (Marber 1993, 2003, 2009). This has resulted in unprecedented socioeconomic progress in lower- and middle-income countries that make up some 85% of the planet's population—more than 5 billion people. The BRIC nations (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) alone are half this total, or roughly nine times the population of the US. As measured by the United Nations' Human Development Index (HDI), these regions have dramatically closed health and education gaps between themselves and wealthier OECD countries since 1980.

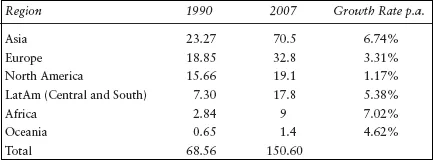

Figure 1.1 Regional tertiary student trends, 1990–2007 (in millions).

Source: UNESCO.

With newfound wealth, many developing countries now have record numbers of students seeking tertiary schooling. According to UNESCO, from 1990 to 2007,2 the number of university students worldwide more than doubled to 150 million with nearly all gains coming from emerging markets. Africa has grown the fastest (off a very small base), with Asia expanding almost as fast but enrolling nearly half the world's students. Most advanced regions—like the US, West Europe, and Japan—are seeing flat to moderately rising enrollments. Europe's recent doubling represents the expanded European economic zone, which grafted on more population from former Soviet Union countries. Oceania, too, grew faster due largely to strong immigration trends from buoyant Asia to Australia and New Zealand.

This worldwide demand for higher education is unprecedented and will intensify as it becomes increasingly difficult to compete for employment in a globalizing economy. Individuals, schools, employers, and governments understand that a “good” or “better” education is, and will continue to be, a key to future success. Therefore, a new global marketplace for higher education is evolving. What are the consequences of such trends? Are there any preferable pathways? Cleary, this field requires close monitoring and analysis as it unfolds.

The rapid increase of college-ready students may lead to economic and social progress, but it also adds enormous unexpected pressures on individuals, institutions, and governments. Like economic globalization, education's globalization is fraught with great opportunity amid great anxiety. Universities take decades to develop effective curriculums, methodologies, and faculty, and few emerging market governments have prepared adequately to meet new needs in education. Schools in advanced economies have taken note of this growing global demand for higher education and are examining strategies to attract the best students, faculty, and administrators from an increasingly global pool that now includes many from emerging markets. Several English-speaking universities have launched aggressive international recruiting programs and permanent overseas offices. Dozens have established satellite campuses and research outposts, as well as joint-venture partnerships with foreign institutions. Technology, too, is having a substantial impact, with hundreds of schools expanding their online capabilities to reach capable students everywhere.

With more countries competing economically, many governments are attempting to build what Drucker calls “knowledge societies” (Drucker, 1954, 1967, 1993). In a world where low-cost manual labor has become cheap and ubiquitous, critical thinking skills and “knowledge workers” are the elusive goal. Indeed, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) notes that creativity, knowledge, and access to information are increasingly powerful engines driving economic growth and promoting development in a globalizing world (2010). This has fomented a mad rush both in emerging markets and advanced economies to keep up with huge bets being made in higher education everywhere.

EMERGING MARKETS: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE

Up until the mid-20th century, a majority of the world's population was illiterate.3 It has only been in the last two generations that universal primary and secondary education has become the global norm. And while statistically insignificant privileged classes have had access to higher education for the last few centuries, mass tertiary education has a relatively short history, particularly in emerging markets.

That is not to say that universities did not exist in these regions. On the contrary, some of the oldest seats of learning come from what we call “emerging markets.” Nalanda University in northeastern India, for example, may be the considered the world's first model of modern higher education. With some 10,000 students and 2,000 professors, Nalanda was founded in 427 CE and survived for nearly 800 years, devoted largely to Buddhist studies as well as fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and politics.4 Surprisingly, the world's oldest continuous university today is Moroccan: the University of Al-Karaouine in Fez was founded in 859 CE, more than two centuries before the great western universities in Bologna (1088 CE), Oxford (1109 CE) Salamanca (1134 CE), and Paris (c. 1150 CE).

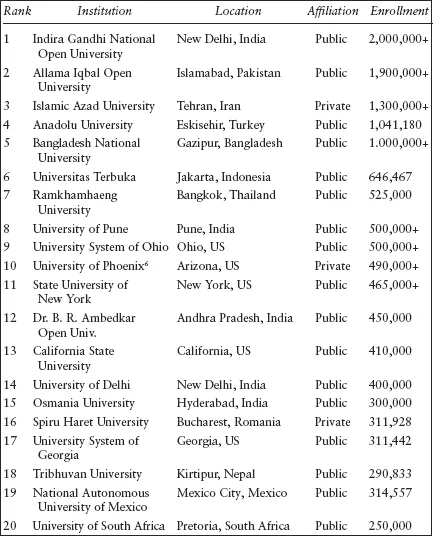

Figure 1.2 The largest 20 universities worldwide by students, 2012 (estimated).5

In fact, when looking around the world today, some of the largest universities are based in emerging markets. Many of them are vestiges of formerly centrally planned economies that include large state-run multi-campus systems, some with more than 2 million students (see Figure 1.2). However, the quality and access to these institutions has begun to be questioned by governments, students, and universities both inside and outside such countries. Many of these systems have been shaped by decades of inward-looking government policies that predate the globalizing world. As such, these schools—like corporations—must rethink their missions, resources, programs, philosophies, and outcomes for effectiveness in the 21st century.

Emerging markets comprise a wide range of countries from large, extremely poor, agrarian societies to small higher-tech exporters, most with very mixed socioeconomic populations. The quality and state of higher education varies per country based on their respective history, demographics, and—most importantly—secondary school systems. But while the quality levels vary dramatically from country to county, these regions are entering the global education network not only by adding an unprecedented number of students, but also by contributing more scholarly articles. Seven of the top 20 publishing countries currently are emerging markets including China (2nd), India (10th), Russia (12th), South Korea (14th), Brazil (15th), Taiwan (17th), and Poland (19th) (SCImago, 2007).7

China and India

As the world's second largest economy—perhaps the largest by 2030—China often grabs the headlines when surveying overseas global higher education. While its sheer size alone warrants serious study, China's speed and penetration rates in higher education are objectively impressive. In 1970, China enrolled less than 50,000 postsecondary students in a population nearing one billion people, a tiny percentage rooted in the Cultural Revolution's anti-intellectual policies. By the early 2000's a remarkable 17 million people enrolled—roughly the same number as enrolled currently in the US. Today, China has over 25 million students enrolled in higher education, and graduation rates are equally impressive (Xinhua News Service, 2007). UNESCO notes that in 2007, China had surpassed the US in total college graduates.

China's progress has been built on sound mass primary and secondary education. Even with 1.3 billion people, China's official literacy rate is over 92% (20-plus percentage points higher than India's), with high completion rates for secondary school, and key cities such as Shanghai post some of the world's highest Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores.8 China also mandated that English as the nation's second language be taught nationwide from kindergarten upward, so most college-bound students have moderate fluency. Approximately 30% of the school-aged population goes on to some form of higher education. Such expansion has also resulted in scholarly output. According to a study by the National Science Foundation, China's publishing grew from 9,061 articles in 1995 to a remarkable 56.805 in 2007, or roughly 25% of all global academic publishing growth for this period.9

China has a state-dominated university system, with entrance gained through scores on the infamous gaokao—the rigorous three-day entrance exam. In 2010, 9.3 million students tested for 5.7 million available university places, down slightly since 2008's peak of 11 million students (Xu, 2011). While this reflects demographic aging trends (China's one-child policy has led to a population with median age of 35.5 versus India's 26.2 years), it also indicates that college-bound students may be seeking alternatives to the state-run university system. There are approximately 2,000–3,000 private schools (including for-profit models) offering campus-based and online distance in China, some for degrees, others for vocational training.10

For the more ambitious students, one attractive option has been to study abroad even though the costs are often multiples of Chinese state tuition (capped at roughly $2,500). While the number of gaokao sitting students has been dropping since 2008, students studying abroad have risen over the same period by 24% to 1.27 million (Ning, 2011). In the past, the trend was more prevalent in PhD and professional programs, but it is increasing in undergraduate education.11 There is even a new niche for preparing and packaging wealthy Chinese children for Ivy League schools, including English lessons, SAT preparation, and essay writing (Demick, 2011).12

Admittedly there is a clear quantity problem—a simple shortage of Chinese tertiary capacity—but quality is also questionable. Few inside or outside China would claim that any Chinese university is on par with the best US or European schools, and none of the major world rankings rate Chinese schools very highly as of mid-2012.13 China's MOE takes such rankings very seriously and began legislating greater resources 15 years ago, when it commenced a major overhaul of the system by closing weak colleges, merging many, and placing others under Chinese provincial manag...