![]()

1 Introduction

Most crime, whether measured by official statistics or by studies of the ‘dark figure’ of unrecorded crime, is property crime. Most of the property crimes that come before the courts and which are reported by the media involve the involuntary transfer of goods or money, normally by stealth, more rarely by intimidation or violence. Fraud, then, is an unusual type of crime because the fraudster gets the victim to part with his property voluntarily, albeit (by definition) under false assumptions about the transaction. The fraudster may be likened to Milton’s sorcerer, Comus, who exults in his ability to ‘wind me into the easy-hearted man and trap him into snares’.

Fraud is often depicted as a ‘new crime: as a ‘twentieth century crisis’ (Bequai, 1978). We shall examine the extent to which it may properly be regarded as a modern ‘crisis’, but it is a mistake to view it as a new phenomenon. Activities such as forgery and counterfeiting – particularly the debasement of coinage – were problems for the Roman and the Byzantine states, and in England, were prohibited as early as 1292 by the Statutum de Moneta: the Statute of Purveyors of 1350 made them treasonable offences. The obtaining of goods and money by false pretences has been prohibited under Anglo-Saxon common law and statute law since at least the middle ages. Insolvency frauds that would be considered as being substantial if they occurred today were carried out in the nineteenth century. (See Levi, 1981; Styles, 1983; and Sugarman, 1983 for some relevant historical discussion. Styles’ analysis of the period 1550–1780 demonstrates the considerable amount of embezzlement and pilfering by ‘out-workers’ in the woollens trade that existed even before the era of the factory and the creation of an industrial proletariat.)

Yet to state that there is nothing new about fraud is not to show that it is not the modern crime par excellence. With some honourable exceptions (Hall, 1952; Mcintosh, 1975), an aspect of crime too often neglected by criminologists is that as the forms of social and economic organization change, the forms of criminality change. It appears to be mere tautology to state that there could be no autocrime without the invention of the car, no computer fraud without computers, and no credit-card fraud without credit cards, but the dynamics of crime are not simple truisms. Just as – however distressingly – not all those people who experience a ‘need’ to be rich will actually become rich, so too there may be a gap between the number of people who – if they are not prepared to go ‘straight’ – may need to change the pattern of their criminality and the number who will actually be able to achieve this goal. In reality, then, not all would-be fraudsters will be able to achieve their ambitions. However uncomfortable it may be for those who wish to blame either ‘the offender’ or ‘the victim’, if we wish to account for patterns of victimization, we must try to integrate both potential offender and potential victim conduct.

General changes in the distribution of goods and money can have major – and often unanticipated – effects upon crime: for example, improved protection for cash kept in safes has undoubtedly increased the relative attractiveness of armed robbery, as almost the only vulnerable points for criminals are cash in transit or in the tills. (The kidnapping of managers’ families may not be sufficient, because as a security measure, the manager may not have the ability to open the safe on his own.) As the carrying of cash becomes less common – only the prevalence of the ‘black economy’ sustains its popularity! – intending criminals are forced towards the exploitation of ‘plastic money’, even though they may come by it as a result of traditional crimes such as muggings, thefts from offices, and burglaries. ‘Long-firm fraud’, in which sham businesses are set up as fronts to obtain large quantities of goods on credit from manufacturers, has long been a growth point for the more sophisticated ‘villains’ (Levi, 1981). During the 1980s, it has become a common pastime for ‘retired’ armed robbers in search of less physically and emotionally demanding activities (and lighter sentences). It seems, therefore, that for adults in all socio-economic groups, particularly if greater success is achieved in the prevention of autocrime and burglary, fraud will become the modal crime of the future.

Barriers to entry – whether technological or social – are an important feature of crime for gain. If one cannot make use of stolen ‘plastic money’ (or cannot find anyone to buy it), there is little point in mugging people whose disposable assets can be accessed only through their credit and cheque cards. If one cannot operate and obtain access to a computer, computer fraud is impossible. Unlike ‘mugging’, commercial fraud is not an ‘equal opportunity crime’ and to the extent that there is disadvantage or discrimination by class, gender, ethnicity, or religion in occupying particular roles, the opportunities for particular types of fraud are correspondingly restricted. Neither physical opportunity nor technical knowledge are sufficient to explain involvement in crime, but it is not solely because of their innately superior morality that there are so few female and/or black management fraudsters in Britain or even in the United States! (See Carlen, 1985, and Zietz, 1981, for some relevant data on female fraud.) In short, opportunities for crime may exist in a theoretical sense, but people have to find ways of using cars, computers, and credit cards for crime, just as over the last century, they had to find new ways of cracking open safes as safe technology improved.

Sometimes, technological changes can make old kinds of crime more freely available. An example is the development in the mid-1980s of Quick Response Multicolour Printers, whose laser scanners are so sophisticated that they can even reproduce the tiny blue and red silks that are embedded in green US dollar bills and recreate the slightly raised ink of the engraving process. When these mass photocopiers become readily available – probably in 1987 – they will transform counterfeiting from a highly specialized craft to a form of crime that will be open to all. Organizational changes in markets also can make fraud easier: an example is the so-called 1986 ‘Big Bang’ when The Stock Exchange in Britain shifted from ‘single capacity’ – brokers do not hold shares on their own account but act only for their clients, and buy or sell shares only through separate firms called ‘jobbers’ – to ‘dual capacity’, whereby the same firm can both make markets and deal on behalf of clients. Technological developments intended for ordinary commercial transactions can facilitate their tasks: examples include not only computers but also international direct-dialling telephones, telexes, computer-aided despatch systems, and facsimile senders, which all enable fraudsters to distance themselves geographically from their targets. The spread of offshore banking and investment schemes has benefited multinational corporations and fraudsters alike: provided that they have confidence that they themselves will not be defrauded, both are inclined to move to where costs and levels of regulation are lowest.

Economic changes are important, too, in altering the desirability of particular forms of fraud. In the mid-1980s, documentary fraud in the shipping of goods has taken over from faked insurance claims for allegedly lost vessels and from overstated claims for vessels sunk deliberately into trenches deep in the ocean. The reason is that due to the excess of supply over demand in the market, ships themselves have become so cheap that they are worth less than their cargoes. So as long as this oversupply-continues, scuttling – at least without first offloading the cargo – will remain relatively unprofitable. The faking of documentation may require skills that the simpler ‘scuttlers’ do not possess, and this may constitute a technical barrier to entry for some (though not many!) potential maritime fraudsters.

The growth of recorded fraud and convicted fraudsters

The twentieth century has witnessed a vast expansion in recorded fraud and in the number of offenders who are officially dealt with for fraud. This is a trend that fraud shares with other forms of crime. There is a great deal of disagreement among historians over the extent to which rises in recorded crime reflect (1) ‘true’ increases in the amount of law-breaking, (2) the growing enthusiasm of state bureaucracies to claim competency at finding ‘professional solutions’ to crime, and (3) the increased willingness of victims of all social classes to use the police to deal with their conflicts, albeit that different crimes have different reporting and recording rates (Foucault, 1977; Gatrell, 1980; Reiner, 1985, Chs 1 and 2; Sparks, 1982).

There has been an increase not only in the absolute but also in the relative importance of fraud, which was a mere 0.5 per cent of indictable crime in 1898 but had risen to become 4.6 per cent of indictable crime by 1968 before falling to 3.8 per cent of ‘notifiable offences’ in 1985. (The offences included within the category of fraud remained fairly stable throughout the period up to the substantial changes in the law of fraud brought about by the Theft Act, 1968.) The number of recorded offences of fraud quadrupled between 1938 and 1968. Since then, the fraud figures have stabilized, although some of this stability may be more apparent than real, due to the ‘crime-deflating’ effects of changes in recording procedures in 1980, when the Home Office, in an attempt to improve consistency, directed that ‘continuing offences’ should be recorded as one offence rather than as a multiplicity of offences.

The current official recording procedure is that if someone steals a cheque book and cashes thirty cheques, it should count as one recorded crime rather than as thirty. Before this, informed sources suggest that if the cheque offences were cleared up, they would have been put down as thirty; if they were not cleared up, they would count as one! Even now, the situation is complex, and is expressed with modest understatement as follows:

‘The recording of offences of fraud and forgery often requires difficult judgments to be made as to what constitutes one offence. Cases may involve a large number of instances of deception or forgery and sometimes, several offenders acting together, perhaps in different groups on different occasions. Because of these problems the recorded numbers are particularly sensitive to variations in recording practice.’

(Home Office, 1985a:29)

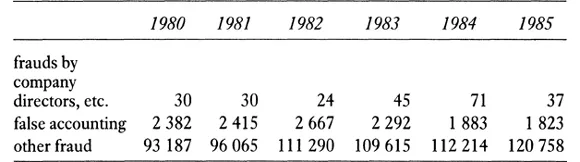

The effects of these changes are impossible to quantify, but there is no reason to suppose that the drop in ‘false accounting’ from 5,227 in 1979 to 2,382 in 1980, and in ‘other fraud’ from 97,438 in 1979 to 93,187 in 1980, were due to a falling off in the amount of fraud. Bearing in mind the statistical caveat above, it is noteworthy that recorded fraud has increased by an average of 5 per cent annually since 1980. The figures are set out below in Table 1.

Table 1 Recorded fraud in the 1980s

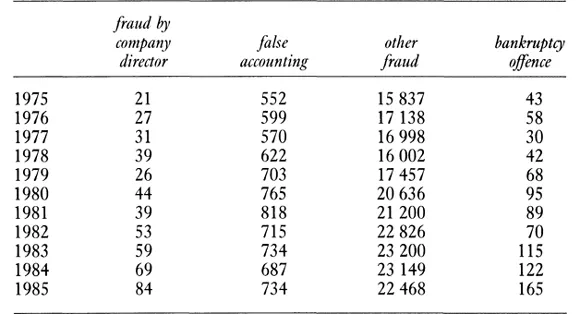

Given the unpredictability of the time-lagged effect on involvement in fraud and, particularly, on the filtering of cases through the policing and prosecution process, it would be hard to build up an econometric model of the relationship between fraud and the volume and/or profitability of business. Furthermore, problems of reporting behaviour and of policing resources and attitudes – discussed in later chapters – would bedevil the validity of any such model. However, not surprisingly, the increases this century in the number of recorded frauds have been accompanied by rises in the number of convicted offenders. At the end of the First World War, there were 1925 people convicted for fraud and false pretences, of whom 354 were convicted in the higher courts of Assize and Quarter Sessions. This figure rose to 2749 in 1938, to 2954 in 1948, to 4188 in 1958, and to 9267 in 1968 (of whom 1200 were convicted at the Assizes and Quarter Sessions). So the numbers convicted of fraud almost quintupled, while the numbers convicted of fraud at higher courts more than trebled, over the 50-year period to 1968. Again, changes in the Theft Acts (1968 and 1978) make comparison difficult, and the extensive range of offences in the Home Office classification of ‘other fraud’ is particularly unhelpful, but there has been a substantial rise in convictions over the past ten years, mostly for relatively minor frauds rather than for major scandals that attract media attention and which, as we shall see in later chapters, are seldom prosecuted. Table 2 sets out the increase in numbers convicted of or cautioned for fraud during the past decade.

Table 2 Offenders found guilty of or cautionedforfraud, 1975–85

As I noted when considering the recent changes in recorded fraud, the effect of administrative changes has been to deflate rather than to inflate the offender statistics in this area. For example, approximately 140 offenders were ‘lost’ as a result of changes in indictable offences brought about by the Criminal Law Act (1977). Although it is possible that these statistical rises in both fraud and fraudsters dealt with officially may be due to increases in the levels of formal social control of fraud, this does not appear to be a plausible explanation, particularly for the past decade. There have been no significant legislative changes bringing previously uncriminalized activities within the ambit of the criminal law. There has been a modest rise in Fraud Squad manpower nationally over this period – from 232 in 1971 to 588 in 1986 – but such squads tend to deal with lengthy investigations into relatively small numbers of people. Nor is there evidence of major changes in victim reporting policies, the proactive redirection of CID manpower into fraud investigation, or more active prosecution policies on the part of the police, the Department of Trade and Industry, or the Director of Public Prosecutions, that could enable one to explain away all the rise in fraud and fraud convictions as a mere artefact of reducing the ‘dark figure’ of fraud and unprosecuted fraudsters. There have been some slight changes in policing, as we shall see in Chapter 5. However, it appears that the rise in fraud is a real one. Indeed, this is consistent with the arguments set out earlier which seek to account for why fraud can be expected to become an increasingly popular form of crime.

The growth of fraud internationally

Internationally, a similar process of growth of recorded fraud and convicted fraudsters has occurred. Here, the absence of research makes it harder to assess the extent to which changes in crime rates may be largely artefacts of changes in law or policing resources. However, the figures are interesting nonetheless. In Hong Kong, the Independent Commission Against Corruption has prosecuted 1478 persons for corruption in the private sector since its inception in 1974, with a conviction rate of 76 per cent. Prosecutions have risen from 17 in 1974 to 96 in 1976, to 113 in 1980, to 284 in 1983, and to 311 in 1984. In Eire, there has been a substantial rise in recorded fraud, which has doubled during the 1980s. North America and Continental Europe have also experienced a recorded fraud boom.

Fraud data from the United States are poor, partly because the Uniform Crime Reports – focusing as they do upon personal and household victimization of a more conventional kind – do not include it. However, in the period 1973–82, fraud experienced the largest percentage rise of any category of arrests (88.8 per cent); forgery and counterfeiting arrests came a close second (72.6 per cent); and embezzlement also rose 10.1 per cent over this period (US Department of Justice, 1985:464). It is largely an artefact of the differential nature of US federal, state, and local jurisdictions, but embezzlement and fraud was the largest single category of criminal case filed in US District (Federal) Courts in 1983: 22.1 per cent of all cases filed, compared with 6.7 per cent for forgery and counterfeiting; 9.8 per cent for larceny and theft; and 6.4 per cent for homicide, robbery, assault, and burglary combined.

In Canada, frauds accounted for 8.7 per cent of property crimes and 5.7 per cent of Criminal Code violations reported by the police in 1984. Credit-card fraud has increased by 25 per cent per annum since 1978. In 1984, it accounted for 13.25 per cent of fraud, and cheque-card fraud traditionally accounts for about 60 per cent of fraud in Canada. So three-quarters of recorded fraud is banking-related, generally of a relatively minor kind.

In Sweden, recorded fraud other than embezzlement increased from 14,653 cases in 1950 to 91,080 in 1984. Embezzlement has increased over the same period from 5469 to 8959 cases. The number of recorded frauds has actually dropped during the 1980s, possibly due to changes in recording procedures.

Elsewhere, the information is patchy. I have been unable to obtain from Interpol any data more recent than 1982, and it is far from certain that the numbers are compiled accurately. National classifications of the denotation or boundaries of fraud differ also. Indeed, it seems almost certain that the differences between the fraud rates per 100,000 population of the different countries set out below are the result of variations in classification systems (and in police resources and recording policies), and that they do not provide a properly comparable data base. For example, to take advanced industrialized nations alone, it is implausible that citizens of Sweden should be on average 3 times as likely as those of Australia to be the victims of fraud; or that the Swedes should be 4 times as likely as the English and Welsh, and 44 times as likely as the Italians to be fraud victims! Consequently, it may be as well to focus upon the intranational change rather than international comparisons.

But bearing in mind these reservations, over the period 1977 to 1982 (except where stated, because 1982 data are not available), the rate of recorded fraud offences per 100,000 population rose most dramatically in Austria, from 212 to 264; in Belgium, from 4.5 to 14.6; in Korea, from 119 to 218 (in 1981); in Denmark, from 140 to 235; in Spain, from 21 in 1978 to 42 in 1982; in Finland, from 323 to 586; in Japan, from 61 to 89; in Lebanon, from 6 to 17 (in 1981); in Monaco, from 375 to 528; in New Zealand, from 415 to 646 (in 1981); in the Netherlands, from 25 to 39; in Scotland, from 208 to 309 (in 1981); in Northern Ireland, from 97 to 179; in Senegal, from 13 to 23; in Singapore, from 37 to 80; in Sweden, from 693 to 1168 (in 1981); and in West Germany, from 434 to 602.

On the other hand, the rate of recorded fraud per 100,000 population actually fell in the Bahamas, from 205 to 139; Chile, from 130 to 105; Taiwan, from 12 to 7 (in 1981); Israel, from 296 to 205; Italy, from 41 to 26; Malaysia, from 16 to 12; Qatar, from 12 to 6 (in absolute numbers of offenders, from 36 to 18!); and Zambia,...