- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developmnt Conscience Ils 242

About this book

First Published in 1998. This is Volume I in the Sociology of Behaviour and Psychology series. This work was first written as a Ph..D. thesis and submitted to the University of Nottingham under the title 'Conscience and Psychopathy: an investigation into the nature and development of the conscience'. It explores the problems of definition and assessment as well as outlining the results of the assessments made from listening to forty tape-recorded interviews: twenty with subjects diagnosed as psychopaths and twenty with normal subjects, acting as a control group.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter Three

Social Factors in Conscience

I. One Hundred 15-Year-Olds

THIS section describes the groups of 100 schoolboys used in the second part of the investigations as described in Chapter I, and gives details of the instrument used for the assessment of parental attitudes.

Educational Background

The subjects were in their fourth year of State secondary schooling, which means that all attained their fifteenth birthday within the school year. The entire fourth year (48 boys) of a boys’ Grammar School was interviewed, apart from one boy who refused interview and two absentees. The entire fourth year (15 boys) of a small Boys’ Secondary Modern School was interviewed, apart from two boys whose parents refused permission. A random example from the entire (male) fourth year of another Secondary Modern School yielded a total of 35 recorded interviews—but six interviews failed to record. The total of 100 interviews was then achieved by asking the headmaster of another Grammar School to select 2 boys from his fourth year. Educationally, the smaller of the two Secondary Schools was inferior, and helped to make the sample representative of both the full range of scholastic ability and social class. Owing to the fact that the interviews took place in the final (Summer) term of the fourth year, the Secondary Modern Schools, in particular the first one, had lost a proportion of their boys when they achieved their fifteenth birthday earlier in the year. Thus the average age of the Grammar School boys was higher than that of the Secondary Modern sample. The ‘departure rate’ at a Grammar School is negligible, and indeed the Grammar School sample showed the full range of ages from 14:10 to 15:10, the mode lying at 15:6, the mean at 15 years 4 months. The Secondary Modern Schools together showed the full range, but clustered towards the younger ages, the larger averaging at 15 years 2 months, the smaller at 15 years. The average for the total sample was 15 years 3 months. It is not likely that those in the Secondary Moderns who left during the course of the year seriously upset the balance of the sample as a whole. All those entitled to leave in the smaller school had left, and only 7 boys from the larger group could have left earlier if they had wanted. Thus, leaving school for the Secondary Modern schoolboy appears to be fairly normal practice. The 7 Secondary Modern boys who remained may have slightly upset the balance, for on average they emerged high on all three attributes—thus confirming their ‘conscientiousness’! A difficulty therefore arose when the effect of age on conscience was considered, and it was necessary to consider the samples separately. By itself the average age difference between the samples of only two months was not sufficient to bias the sample seriously when the effects of other variables were considered.

Social Class

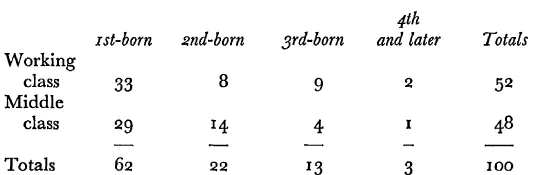

Representatives of all the Registrar-General’s social class divisions were included in the sample. For the purposes of statistical analysis, Social Class III was subdivided using the R-G distinction between Manual (M) and Non-manual (Nm) occupations. Social Class III M contained the highest number (38) of subjects. The fathers of many of these subjects were skilled workers in local engineering factories. With five sons of professional fathers (Class 1), 22 subjects in Class II, 21 Class III Nm, 13 Class IV and one Class V, a good representation of both middle- and working-classes was achieved. For some analyses it was found convenient to make a division between ‘middle-class’ (Social Classes III Nm, II and I—48 subjects) and ‘working-class’ (Classes V, IV and III M—52 subjects). Correlations are also reported using the six divisions as a basis of ‘scores’ from ‘0’ to ‘5’.

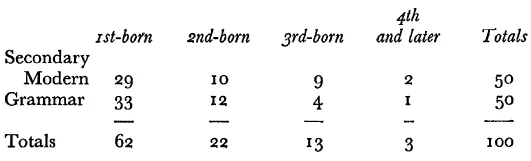

As expected, the social classes were not evenly distributed between the schools. Whilst 66 per cent of the Grammar School subjects were middle-class, only 30 per cent of the Secondary Modern subjects were middle-class (a significant difference). As indicated also by the Vocabulary Test, educational achievement was highly significantly related to Social Class.

Family Background

Subjects were asked whether or not their mothers went out to work. In all, 38 mothers out of 99 (one mother was deceased) went out to work either part- or full-time. The proportions of middle- and working-class working mothers were virtually identical, but a greater proportion of the mothers of Secondary Modern boys went out to work, the difference between the two educational groups being just significant. Similarly, whilst there was a trend, though not significant, towards greater religious training by the parents of the Grammar School boys against those of the Secondary Modern boys, the proportion of working-class parents giving ‘high’ religious training (8 years or more attendance at Sunday School or Church up to the age of 14) was identical with the proportion for middle-class parents.

As expected middle-class boys tended to come from smaller families. Twice the proportion of working-class boys came from ‘large’ families (more than three children) as did middle-class boys, the difference being quite significant. The proportion was the same for Grammar School as against Secondary Modern boys, the latter coming from larger families. However, when the ordinal position in the family was considered against social class and educational achievement there were no consistent trends evident. Whereas the working-class boys had a higher proportion of first-borns, they had a lower proportion of second-borns and a higher proportion of third- and later-borns, as may be seen from the table. This is important in view of later findings.

Ordinal Position

Data were also obtained for parental separation. The number of years each subject had been separated from either parent up to the age of fourteen was noted. Only 12 subjects reported separation from one or both parents for one year or more. 5 of these were cases of parental separation for short periods owing to Army service. 2 fathers had died and 3 fathers had deserted home, all in the child’s later years. Only 3 cases of maternal separation were reported, two for just one-year periods in late infancy owing to illness, and one a four-year period in late childhood. The picture was generally one of great stability of family life, particularly in the earlier years of childhood.

Assessment of other factors

Parental attitudes were assessed using a shortened version of Earl S. Shaefer’s ‘Child Perception of Parent Behaviour Inventory’. This inventory—not yet published—was designed to measure sectors of Shaefer’s ‘circumplex model’ for parental behaviour (see Schaefer, 1959). Schaefer claims that all studies of parental behaviour demonstrate two major dimensions—Love v. Hostility, and Autonomy v. Control. His own analysis of data from the Berkeley Growth Study shows that most of the variance on twenty-five scales measuring different aspects of maternal behaviour is accounted for by those dimensions. Schaefer, Bell and Bayley (1959) describe an interview method for the assessment of maternal behaviour, and Bayley and Schaefer (i960) present evidence showing the relationship between maternal behaviour and the emotional development of the child. Evidence using the twenty-six scales which comprise the Child’s Perception of Parent Behaviour Inventory, with both maternal and paternal forms, show again the prominence of the two major dimensions. In Schaefer’s words (personal communication) ‘Examination of intercorrelations of the scales for small samples shows that much of the variance does, in fact, fall within the two dimensions. The major dimension is of positive v. negative description of parents best defined by Ignoring, Neglect, Rejection and Negative Evaluation as opposed to Sharing, Equalitarianism and Emotional Support, The control dimension is best represented by Strictness and Punishment.’ Bayley and Schaefer showed performance of the mother on the two major dimensions to be variously related to normal boys’ overall happiness at different ages. The boys ‘did well’ if their mothers were loving at an early age and granted autonomy at adolescence. The scales best defining the two dimensions were used in this study. The other scales used include ‘Control by Guilt Feelings’, ‘Suppression of Aggression’ and ‘Intrusiveness’. The first comes very close to the concept of ‘psychological discipline’ as used by Sears, Macoby and Levin, and involves the technique of ‘withdrawal of love’, a technique which they found to be typical of higher social classes, and to be related to displays of guilt feelings by the child. A similar concept is that of ‘induction’ as opposed to ‘sensitization’ techniques of discipline, terms used by Aronfreed (1961). Induction techniques involve rejection of the child, showing that the mother is hurt or disappointed. Such methods tend to ‘induce’ in the child internal reactions to his transgressions, independent of the external stimulation. Sensitisation techniques are direct verbal and physical assaults on the child, and depend for their efficacy on the external threat of force to arouse fear. Aronfreed likewise found induction techniques more common in higher social classes, and to be productive of guilt reactions in the child, ‘Suppression of aggression’, would also be supposed to be productive of guilt reactions, of ‘intropunitive’ rather than ‘extrapunitive’ reactions. ‘Intrusiveness’ is closely allied to ‘psychological’ rather than direct physical control. All these scales were therefore included in the assessment of parental attitudes, and the scale items are listed below.

Instructions for Mother’s form of Parent Behaviour Inventory

This is a list of many different things a mother might do or be like. In front of the list of statements are columns of letters. One column has the letter L which means LIKE MY MOTHER. The second column has the letters NL which mean NOT LIKE MY MOTHER. Your job is to make a circle around the letter L if the statement that follows is LIKE your mother, or to make a circle around the letters NL if the statement is NOT LIKE your mother.

There are no right or wrong answers. Guess if you are not sure. There are many questions, so please work quickly. Mark the first answer that occurs to you.

Scale items used in Mother’s form of Parent Behaviour Inventory

1. Sharing plans, interests and activities

1. Takes an interest in the things I like

2. Is interested in the things that make me happy

3. Is interested in my plans and hopes

4. Is interested in what I do

5. Enjoys talking things over with me

6. Enjoys going on drives, visits or trips with me

7. Spends a lot of time having fun with me—playing games, going on picnics, and so forth

8. Enjoys working with me in the house or yard

9. Enjoys doing things with me

10. Has a good time at home with me

2. Emotional Support

1. Still believes in me even when I’m in trouble

2. Makes me feel better after talking over my worries with her

3. Will ‘stand by me’ when I’m in trouble

4. Understands my problems and worries

5. Helps me out when I am in trouble

6. Comforts me when I am in trouble

7. Is able to make me feel better when I am upset

8. Comforts me when I’m afraid

9. Cheers me up when I’m sad

10. Gives me sympathy when I need it

3. Intrusiveness

1. Always wants to know all my secrets

2. Always wants to know exactly where I am and what I am doing

3. Is always checking on what I’ve been doing at school or at play

4. Asks me to tell everything that happens when I’m away from home

5. Always wants to know whom I’ve been with when I go out

6. Keeps a careful check on me to make sure I have the right kind of friends

7. Looks through my personal things

8. Often asks me what I’m thinking about

9. Asks other people what I do away from home

10. Insists that I explain the reasons for my actions

4. Control by Guilt Feelings

1. Feels hurt if I don’t show her that I love her

2. Feels hurt when I don’t follow advice

3. Thinks I’m not grateful when I don’t obey

4. Makes me feel that I owe her a great deal

5. Feels that I should be grateful for what is done for me

6. Feels hurt by the things I do

7. Feels that I do not show enough love

8. Acts hurt when I don’t obey

9. Believes it’s a child’s duty to love his parents more than anyone else

10. Tells me how much she’s suffered for me

5. Suppression of Aggression

1. Doesn’t want me to fight with other children no matter who started it

2. Thinks that ‘children should be seen but not heard’ when grown-ups are talking

3. Doesn’t like noisy or bold children

4. Tries to teach me to control my anger no matter what happens

5. Does not approve of my talking back to older people

6. Does...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Statistical Note

- I. Problems of Definition and Assessment

- II. Conscience in the Psychopath

- III. Social Factors in Conscience

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Developmnt Conscience Ils 242 by Geoffrey M Stephenson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.