- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pali Buddhism

About this book

This is an interdisciplinary and holistic survey of Pali Buddhism, covering philological, indigenous and philosophical approaches in a single volume.

The work is divided into three main sections: Philological Foundations; Insiders' Understandings; and Philosophical Implications.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

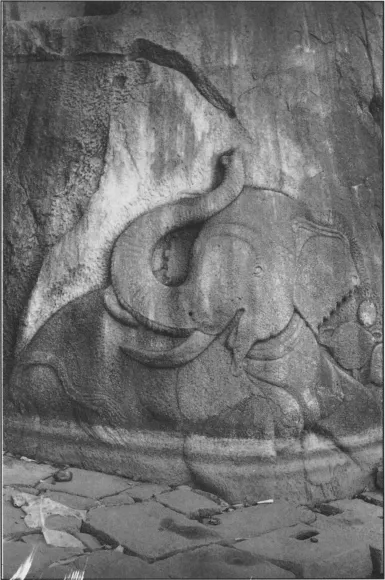

| Anurādhapura (Sri Lanka) | Isummuṇiya Vihiāra complex |

| Relief on rock showing elephant | circa 4th century, Stone |

| Photograph courtesy of the American Institute of Indian Studies, Varanasi, by way of the Archeological Survey of India. Negative number 337.94. | |

Section I

PHILOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS

1

Theravāda Buddhism’s Two Formulations of the Dosa Sīla and the Ethics of the Gradual Path

When Buddhaghosa edited the Sinhala commentaries to compose the Visuddhimagga, he placed sīla, ordinarily translated as moral conduct or virtue, as the initial stage of the “path of purification.” The path itself included the three stages of training, sīla, samādhi and paññā. From that time Theravāda Buddhism has followed Buddhaghoṣa in teaching that sīla stands at the head of the Buddhist path. Although sīla in this sense constitutes a very comprehensive element of Buddhism, Theravādins have traditionally formulated and practiced sīla in terms of the dasa sīla or ten precepts. It is in the form of dasa sīla that sīla has been known and practiced by most Buddhists.

Interestingly, however, Theravāda’s texts and commentaries contain two formulations of the dasa sīla which differ at important points. This article examines the nature and purpose of these two lists of dasa sīla or precepts in order to elucidate the nature and meaning of sīla for Theravāda. Among the questions that are important here are the following: why did the Buddhists postulate these two versions of the dasa sīla with these particular precepts? What is the relation between the two lists and what do these two formulations tell us about the overall meaning of sīla and the system of ethics in Theravāda? How do the lists of precepts relate to the goal or telos of Theravāda?

To indicate in advance something about where these questions will lead us, I would note that according to the Theravāda texts and commentaries, these two formulations of sīla are neither competing nor arbitrary but are grounded in Theravāda’s understanding of the path as a series of soteriological strategies, a gradual path that enables persons at various levels to attain their individual potential. On this gradual path, the role of sīla in general may be described as an element in a Buddhist ethics of virtue which both facilitates and is associated with the ultimate goal of the path, the attainment of the “furthest potential of one’s being,” or Arahantship.1

The first and most widely known formulation of dasa sīla enumerates the ten precepts, as in the following list. I undertake the training precepts of abstention from:

1. Killing/ pāṇātipātā (veramaṇī)

2. taking what is not given/ adinnādānā

3. unchastity/ abrahmacariyā

4. speaking falsehood/ musāvādā

5. intoxication/ surāmerayamajjapamādaṭṭhānā

6. untimely eating/ vikāla bhojanā

7. shows of dance, song and music/ naccagītavādi-tavisūkadassanā

8. adorning the body/ mālāgandhavilepanadhāraṇa…

9. high beds and large beds/ uccāsayanamahāsayanā

10. accepting gold and silver/ jātarūparajatapaṭi-ggahanā

This list of the requirements of sīla is found in canonical Pāli texts such as the Khuddakapāṭha.2 In post-canonical Pāli texts such as the Milinda Pañha and the Mahāvaṃsa, references to the dasa sīla or the ten factors of sīla almost always mean these training precepts, which are also termed the sikkhāpadas. This understanding of sīla has continuity down to recent historical time in Sri Lanka where neo-traditional Theravādins have commonly referred to these precepts as dasa sīla. For example, a very popular Theravāda devotional manual entitled The Mirror of the Dhamma presents these sikkhāpadas or training precepts under the heading of dasa sīla. Similarly in his book Buddhist Ethics, a modern Theravāda bhikkhu and scholar, Venerable H. Saddhatissa, defines and explains dasa sīla as these ten sikkhāpadas.3

The second formulation of dasa sīla stands in the same canon as the first list; it may indeed be older than the first one, but it is much less well known in the practice of traditional Theravāda. This list of dasa sīla has not been used traditionally in rituals and is not referred to in popular descriptions of the precepts. Interestingly, however, it has been rediscovered by Buddhist reformers in the Buddhist revival during the last half century. These reformers, rejecting traditional Theravāda, have accepted this formulation of the precepts and claim that it has a more authentic connection to the true meaning of sīla. This formulation contains the following abstentions. One undertakes to abstain from

1. killing/ pāṇātipātā (veramaṇī)

2. taking what is not given/ adinnādānā

3. wrong sexual conduct/ kāmesu micchācārā

4. speaking falsely/ musāvādā

5. slander/ pisuṇā-vācāya

6. harsh speech/ pharusā-vācāya

7. frivolous talk/ samphappalāpā

8. covetousness/ abhijjhāya

9. malevolence/ byāpādā

10. wrong view/ micchā-diṭṭhiyā

Although this list overlaps with the traditional formulation in the first four precepts, the rest of the precepts are considerably different. They point the way to quite different practices and virtues. The first formulation of dasa sīla reflects monastic practice and the demands of the life of those who have renounced society. The reformers argue, however, that when sīla is understood in terms of the precepts in this second list, it has greater relevance to the spiritual life of lay persons. As a result, it has gained wide acceptance among the middle class laity of Sri Lanka who have been the primary advocates of what may be called the reformist—in contrast to the neo-tradition-alist-viewpoint.4 For example, the leaders of the Saddhamma Friendship Society, a Sri Lankan reformist society of lay persons, have instructed the members of the society to observe only the second list of sīla. Indicating their seriousness about the reinterpretation and practice of sīla, this society refuses even to recite the first formulation at Buddhist ceremonies as Theravādins traditionally have done.

This dispute over the meaning of these two lists of sīla indicates the continuing significance of sīla for the Theravāda tradition. I refer to this dispute, however, not because I wish to side with either group and support their position, but because the dispute itself raises some interesting questions about the meaning of these two formulations of sīla and, through them, the meaning of sīla in general.

The Gradual Path as Context for Sīla and Soteriology

Theravāda developed these two lists of dasa sīla and its entire ethical perspective in the context of its notion of the gradual path. Although many texts in the Pāli Canon seem to imply that the ultimate goal of nibbāna can be attained in this life, the Theravāda tradition came to regard the path to the soteriological ultimate as a gradual one, spanning many lifetimes of an individual. Early expressions of this gradual path can be found in the Pāli Canon itself in the explanations of nibbāna and arahantship. In addition to those texts that tell of hundreds of people attaining arahantship immediately upon hearing the Buddha preach, there are also texts such as the sutta in the Aṅguttara Nikāya in which the Buddha declares that just as the mighty ocean slopes away gradually to the depths, so in his teaching there is a graduated training, a graduated mode of progress rather than an abrupt leap of penetration.5 As I have demonstrated in an earlier article, the arahant ideal seems to have developed from an ideal believed to be readily attainable in this life into an ideal considered to be remote and impossible to achieve in one or even several lifetimes.6 Traditional Theravāda adopted this view and held that arahantship and nibbāna were distant and transcendent goals at the end of an immensely long gradual path than an individual had to approach over the course of many lifetimes.

Early or original Buddhism probably, as Poussin, Weber and others have argued, represented a “discipline of salvation” for, according to the Pāli texts, the Buddha taught that life is suffering and that saṃsāra in all its forms is unsatisfactory.7 Nevertheless as Buddhism developed as an institution it had to address the needs of the “people in the world” who even during the lifetime of the Buddha flocked to him for advice and guidance and who were by definition bound to the wheel of saṃsāra. The gradual path developed as Theravāda’s hermeneutic for balancing the monastic or yogic and the popular or devotional aspects of the tradition. Dumont’s observations about the development of Hinduism seem to apply to Buddhism also: “The true historical development of Hinduism is in the sanyasic developments on the one hand and their aggregation to worldly religion on the other.”8 As Theravāda came to see the goals of arahantship and nibbāna as remote and difficult even for renouncers, it recognized that the paths and the soteriologies of the renouncers and the people in the world were linked by transmigration. The Jātakas clearly taught this in regard to Gautama. Further, the Theravādins recognized that within these two groups or types there actually were tremendous ranges of spiritual abilities and accomplishments. The Pāli Canon contains suttas that describe the Buddha as having the ability to discern these differences in the levels of individuals and to adjust his teachings to them. In one sutta the bhikkhus declare “It is wonderful and amazing how well the Exalted one who knows and sees, arahant, supreme Buddha, ascertains the various inclinations of beings.”9 The commentary to this passage in the Dīgha Nikāya explains that “when he had finished his meal the Exalted one would sur...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Foreword by Ninian SMART

- Introduction by Frank J. HOFFMAN and DEEGALLE Mahinda

- PLATE 1: Anurādhapura elephant

- SECTION I Philological Foundations

- PLATE 2: Anurādhapura guardian

- SECTION II Insiders’ Understandings

- PLATE 3: Anurādhapura moonstone

- SECTION III Philosophical Implications

- Appendix

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Pali Buddhism by Frank Hoffman,Deegalle Mahinda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.