- 315 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Asian Media Productions

About this book

A substantial book on the social practices and cultural attitudes of people producing, reading, watching and listening to different kinds of media in Japan, China, Taiwan, Indonesia, Vietnam, Singapore and India.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Asian Media Productions by Brian Moeran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Asian Media Flows

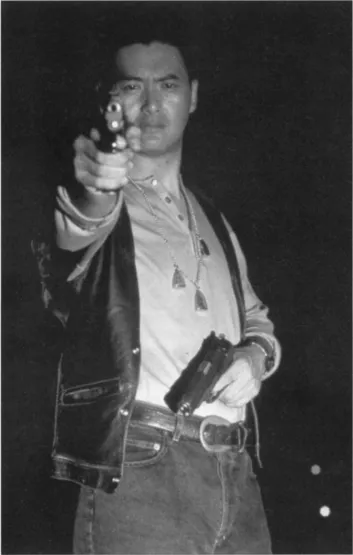

Figure 5 Hong Kong film superstar, Chow Yun-Fat, in another gangster shoot-out

(Photo courtesy of Dermot Tatlow)

(Photo courtesy of Dermot Tatlow)

1

GLOBAL CULTURAL POLITICS AND ASIAN CIVILIZATIONS

The storyline of one of the most important films in the history of Chinese cinema, Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth, features a young soldier from the People’s Liberation Army trekking through the hinterlands of the northern provinces in the late 1930s in search of folk songs from various rural regions. His job was to bring the traditional melodies and lyrics back to his commanding officers so that the peasants’ songs could be transformed into popular tunes praising the communist revolution. The songs were then used as a vital part of the revolutionary force’s national propaganda campaign. Set in a desolate mountain village, the movie also revealed the miserable conditions in which Chinese peasants lived at the time, and still do in some areas today. This masterpiece of China’s fifth generation of filmmakers, and the first of the Chinese ‘new wave’ films, was extremely controversial when it was released in 1985. Abstract, open-ended, and deeply metaphorical, Yellow Earth did not follow the didactic format typical of Chinese cinema after 1949. Chinese cultural authorities thus wondered about director Chen’s intentions and about the audience’s response. Is Yellow Earth a heroic or tragic story? A tale of progress or backwardness? Whose purposes are served by the film, the Communist Party or the Party’s critics?

Complex symbolic forms such as Yellow Earth together with a host of mass media and personal communication technologies exploded onto the world stage in the second half of the twentieth century in ways that have captured the attention of cultural observers everywhere. Film, television, popular music, satellite broadcasting, fax machines, e-mail, cellular phones, and the internet have changed social and cultural realities on a global scale. The rapid proliferation of mediated symbolic displays makes cultural options far more diverse, multiple, and contradictory than ever before. Unprecedented access to mass and micro communication technologies and the robust symbolic spheres those technologies embrace and promote encourage the social construction of new and modified cultural visions, lifestyles, and identities. And as the Chinese cultural authorities have discovered trying to manage their film and television industries since the modernization plan began in 1979, social communication today is not easily supervised or contained. It is within this context of dynamic and indeterminate global communications activity and cultural flexing that Asian media and advertising now develop and interact.

Analyses of communications technology and the symbolic forms they produce and circulate of course must be situated in broader discussions of ideology, economics, politics, and culture. With respect to Asia or any other part of the world, we must look at current cultural developments simultaneously from multiple vantage points. There are national considerations to be sure, but the nature of contemporary cultural activity requires that global, civilizational, regional, and personal spheres be considered as well. The discourses of postmodernity and globalization can help stimulate this multidimensional reflection. We do indeed witness the breaking apart of signs from their original locations and meanings, an increasing capacity to instantly transmit messages globally, and a tendency for certain cultural themes to appear everywhere. At the same time the lived realities of cultural life are becoming more diverse, fragmented, private, and hedonistic, in relative ways, across the social classes. In key respects, culture has been transformed as a social construct away from relatively general and received ‘ways of life’ to more diverse and constructed designer cultures and ‘lifestyles’ (Chaney 1996). At the same time, however, the discursive and lived dimensions of culture as a unifying force also serve the intensified needs of some social collectivities. Both these tendencies – toward cultural privatization and collectivization – are enhanced by the ever-widening circulation that communication technologies give symbolic forms. In this chapter, I will address key elements of this contemporary cultural complexity, using developments from Asia to exemplify how some of these processes unfold.

Global Cultural Politics

Somewhere in the Middle East a half dozen young men could well be dressed in jeans, drinking Coke, listening to rap, and, between their bows to Mecca, be putting together a bomb to blow up an American airliner.

Huntington (1996:58)

Clearly one of the most influential recent theories of how the world’s populations are organized and interact is offered by Samuel Huntington in his book, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996). Huntington makes two particular arguments that pertain to any analysis of Asian media and advertising. The first of these is that the west no longer dominates the world in politics, economics, and culture the way it once did. The west will watch its influence over world resources continue to drop, a development that began in the 1930s. By 2020, western nations will represent or manage only ten per cent of the world’s population (down from 48 per cent a hundred years before), control but 30 per cent of global economic production (down from 70 per cent), 25 per cent of manufacturing output (down from 84 per cent), and less than ten per cent of world military manpower (down from 45 per cent), according to Huntington (1996:90–1). The continued rise of China, India and the Muslim world as global powers will largely define culture and politics in the twenty-first century.

Huntington’s other claim of interest to us here is that the world can be divided into nine ‘civilizations’, which he argues forms the ultimate cultural classification system. At least six civilizations – Sinic, Buddhist, Islam, Hindu, Japanese, and Western – exist in Asia. He believes that civilizational liasons and differences will determine the future of global human relations: ‘We are witnessing “the end of the progressive era” dominated by western ideologies and are moving into an era in which multiple and diverse civilizations will interact, compete, coexist, and accommodate each other’ (Huntington 1996:95). I will use Huntington’s provocative theses to frame this brief commentary on global developments in Asian communication and culture.

Let’s first take up the claim that the west no longer dominates world politics, economics, and culture the way it once did. It certainly makes good sense to reject any view that implies global communication can be reduced to some giant stimulus-response relationship wherein the west inevitably dominates and transforms the rest in all manner of social and cultural life. This is not to say that western nations have not benefited from their exploits over the past 500 years. Clearly they have. But the terms of social and cultural power have become less clear or determined in today’s ‘communication age’ so rich in technology and symbolism. The main reason for this is that two fundamental characteristics of culture – its constant evolution, and its synthetic nature – are fed nutritiously like never before by current practices in global communication. Political, economic, and coercive power no longer dominate as social forces the same way they did years ago. Traditional forms of influence have been joined by ‘symbolic power’ – the use of symbolic forms to shape actions and events – and situated uses of symbolic forms and discourses for personal and social purposes in specific historiocultural contexts (Lull 2000).

Global popular cultures strikingly reflect the cultural metamorphoses and transformations of social influence that are now underway. Perhaps the most visible and criticized symbol of global popular culture is the McDonald’s restaurant chain. One scholar even uses McDonald’s as the paradigmatic instance to argue that a western concept – fast food – and an ensemble of specific culinary products can combine to cause significant negative cultural changes. The author refers to this alleged cultural subversion as The McDonaldization of Society (Ritzer 1993). Such an argument may appeal at surface level, not least because some intellectuals like to use McDonald’s to represent what their personal taste (and class) is not. A more careful analysis, however, reveals that no hamburger hegemony exists (and that the children of these scholars, if not many of the scholars themselves, actually love Big Macs and those skinny, salty french fries). No doubt eating at McDonald’s is a western-style cultural experience, but that does not make it exploitative, corrupting, or unhealthy. To reduce the discussion of global cultural influence by simply attacking a popular restaurant chain does little to explain what’s going on. Even worse, the simplistic argument misleads.

A more insightful look at global McDonald’s is the edited text of James L. Watson, Golden Arches East: McDonald’s in East Asia (1997). Contributors to this book analyze the techniques of McDonald’s commercial food production, the expansion of the franchise into Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and the People’s Republic of China, and most important, the reception of McDonald’s by consumers in those cultures. Watson concludes that East Asian cultures have not been victimized by this culinary nuance, but instead have accommodated, indigenized, and generally enjoyed it. The way this has happened reflects a much larger issue than ‘fast food coming from America’. It gives empirical evidence for understanding the complexity of contemporary cultural activity in the ‘global ecumene’ (Hannerz 1992, 1996). Why wouldn’t McDonald’s be successful in Asia? Are the world’s peoples bound to eat the same food, and take it in the same way as their parents and grandparents? Should we expect cultures to be so static?

Watson thinks not: ‘Culture is not something that people inherit as an undifferentiated bloc of knowledge from their ancestors. Culture is a set of ideas, reactions, and expectations that is constantly changing as people and groups themselves change’ (Watson 1997:8). Culture has always been organic and dynamic, but today’s global flow of people and artifacts of all kinds demands that the organic quality of life become more differentiated, and that the changes will come and go more quickly than ever before. The McDonald’s phenomenon should thus be viewed as part of a relatively fast-paced ‘revolution in family values that has transformed east Asia’ (Watson 1997:8), a profound change that has been complemented, but not caused by western popular culture. McDonald’s therefore may indeed be a paradigmatic case, but it is one of global cultural change, not subversion. The phenomenal success of the hamburger franchise speaks loudly and clearly of its far-ranging appeal and acceptance.

Let’s broaden our discussion of the cultural consequences of postmodernity and globalization. Along with McDonald’s, we’ll bring into consideration another common target of critical inquiry – the Disney Corporation. In the summer of 1998, one of McDonald’s biggest promotions in the United States and around the world was a marketing tie-in between its ‘Happy Meals’ and the Disney animated film, Mulan. We can use this combination of popular culture elements to describe key aspects of how various forms of influence are constructed in the global play of economic and cultural forces.

Hollywood films, television programs, computer software, popular music and nearly every type of popular culture originating from the United States or any developed nation operates with the assumptions of a global market. This practice understandably has alarmed some observers – scholars, journalists, and tourists among them – who have noted the increasing presence of western, especially American, pop culture iconography in foreign countries (often in expensive hotels, restaurants, and shopping areas) and quickly draw negative conclusions about the influence they believe such materials have. Like McDonald’s, Disney has been an easy, frequent target of critics. A classic example of the typical criticism is a book by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart (1972), a commentary on the supposed devastating effects that Disney comic books and other media forms have wrought in South America. Many other books which promote this ‘cultural imperialism’ view of the global political economy could be cited here. A poignant and necessary critique of the cultural imperialism perspective is John Tomlinson’s work (1991, 1999).

But let’s return to Disney and the film Mulan. Based on a centuries-old Chinese fable, overall Mulan promotes Chinese culture positively to a global audience. At the same time, however, the production is extremely critical of some Chinese traditions. The heroic lead character, Mulan, is a young woman who disgraces her family because she inspires little hope for marriage. When China is threatened by a Han invasion, Mulan disguises herself as a man in order to join the Imperial Army and defend her people. After many exciting battles of wits and weapons, Mulan heroically defeats the enemy nearly single-handedly and wins great respect and admiration from her fellow soldiers and countrymen and women, who in the end discover she is a female. Ultimately, Mulan brings great honor to her family, all the while deflecting attention away from her personal achievements.

Chinese paternalism takes a serious hit in the process. But not only that. Mulan’s constant companion in the action-filled, animated drama is a small and mischievous red dragon who, the story goes, had been deemed incompetent by Mulan’s family ancestors to be their guardian. To the certain surprise of Chinese historians and folklorists, and probably to the dismay of many ethnic Chinese parents all over the world who brought their children to see the film, the voice and personality of the little red dragon is played by Eddie Murphy, a black American comedian-actor still best-known for obscenity-laced, racially-explosive humor and a stereotyped in-your-face urban black ‘attitude’. The little anti-hero dragon doesn’t utter expletives in Mulan, but he does chatter incessantly in exaggerated street slang with a distinct black accent. He is rewarded for his loyalty and daring at the end of the movie when Mulan kisses him while ignoring the handsome Chinese lead male character.

This Disney production makes strong statements that problematize gender, culture, race, and family. Some of the statements reinforce traditional Chinese culture, others contradict and ridicule it. Lots of anti-social cinematic clichés are used too, presumably to keep the attention of the young audience. Children in attendance on the day I saw the film – about half of them apparently of Asian descent – laughed heartily at the many pratfalls and visual depictions of action-packed violence. Stereotypes are everywhere in Mulan. The feared invading enemy, for instance, is shown in the form of dark-skinned predators. Physical exaggerations such as excessively slanting eyes and slumping shoulders permeate the animation. In the end, Mulan’s cross-dressing guise and male affectations are removed in order to normalize her sexually.

This complex and contradictory film stimulated extreme reactions of all kinds. One viewer cried as he told a local newspaper reporter in an area populated by many Americans of Chinese background, the Silicon Valley of California, that watching Mulan made him feel more proud than ever to be Chinese. Other Asian Americans said they were simply happy to be represented, and so positively at that, in any Disney production. Mulan exemplifies an intricate interlacing of cultural representation and interpretation. Though some objections to the film’s portrayal of Chinese and to the violence have been raised, there should be no doubt that overall Mulan has had an extremely positive effect as a cultural message. Moreover, the film has taught people everywhere, including young Chinese, about Chinese culture. Japanese, Koreans, Filipinos, Vietnamese and all other Asian peoples are introduced to this Chinese cultural legend in their own countries not by film producers from China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, or Singapore, but by an American multinational corporation based in southern California, mightily reinforced globally by the McDonald’s promotion. Disney is one of the few corporations in the world capable of creating this inspiring folkloric spectacle of animation and distributing it successfully to a global audience. Even the way the film has been produced demonstrates an unprecedented global interconnectedness made possible by modern communications technology, as Disney assembled the visual and audio elements of Mulan without having to bring all the creative talent together physically in space and time.

The film entered a global media mix of discourses about China. During the same period when Mulan was playing in movie houses worldwide, China was the subject of intense scrutiny and criticism on other fronts. News media were reporting details of the communist country’s sale of nuclear missile technology to Iran; Chinese men were accused of illegally trying to sway American foreign policy through fundraising bribes given to the Democratic Party; Bill Clinton was lecturing the Chinese on human rights during his visit to the People’s Republic; the films Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet continued to call attention to the delicate political and cultural situation in the estranged western region. Even the yuan began to shake in the persistent tremors of the Asian economic crisis.

A ‘Mulan Parade’, with the jive-talking voice of Eddie Murphy as the little dragon introducing the event, was a featured spectacle at the Disneyland theme park in 1998 and 1999, a marketing strategy that promoted the film and the (contested) culture. The money, creative talent, technical expertise, and business management skills invested in Mulan by Disney turned a tremendous profit for the entertainment enterprise. M...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction: The field of Asian media productions

- Part I Asian Media Flows

- Part II News

- Part III Advertising

- Part IV Producing Consumption

- References

- List of Contributors

- Index