![]()

Part I

Introduction

Setting the scene

![]()

1 Introduction

The need for a holistic approach

1.1. Introduction

1.1.1. Overview

The focus of this book is to suggest a precautionary approach (PA) taken in the intellectual property (IP) regime in order to enhance access to medicines in a public health emergency. This book further seeks to promote the harmonization of the PA in the IP and health worlds by fine-tuning the complementary roles of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Trade Organization (WTO), with a view to crystallizing the right to health under globalization.

1.1.2. Research methodology

(1) Parameters

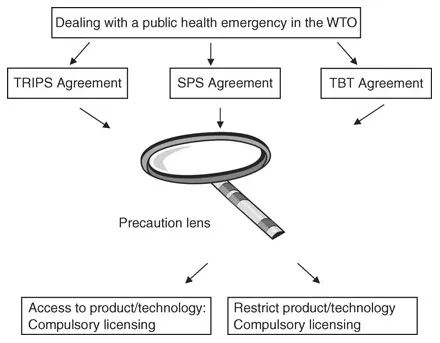

Based on the existing human-rights arguments to enhance access to medicines (section 1.2.1), this book examines the PA in the context of international trade and international health, particularly in the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS),1 the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement),2 and the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT Agreement) regimes,3 and suggests that a safety factor based on the PA can be accommodated into the TRIPS Agreement, particularly in the compulsory licensing provision, to promote access to health technologies and redress the access to medicines dilemma in a public health emergency. (See Figure 1.1.2, Research parameter: Precaution lens.)

Figure 1.1.2 Research parameter: Precaution lens

(2) Limitation

On the one hand, this book aims to promote access to products/technologies which are associated with the reduction or elimination of risks to human health, specifically in the context of access to medicines; on the other hand, this book could also arguably serve as grounds to restrict products/technologies which increase risks to human health and safety. Due to the limitation of research, I will focus on the above first scenario and set the scene on the promotion of access to medicines in a broadly defined public health emergency, which includes global acute pandemics and chronic diseases. The objective of this book is to pioneer an innovative approach to the existing IP/health dilemma by means of adopting a PA and the scientific rationale of risk analysis into the WTO/TRIPS regime. Existing arguments for promoting the right to health serve as a foundation for this book with regard to a broader use of compulsory licensing.

It is argued that health technologies associated with the reduction and elimination of significant risks to human life or health should receive differential treatment by adopting the PA in the compulsory licensing clause in TRIPS. Differential treatment in order to promote access to medicines could be justified by the harmonization of the rationale of PAs in WTO law.

(3) Structure

In order to legitimize the differential treatment of health technologies in IP, Chapter 1 will discuss the tension between IP and the right to health, a broad overview of compulsory licensing, and the implications of other mechanisms for innovation, such as data exclusivity, and the Health Impact Fund (HIF). Chapter 2 will propose a solution of ethical differentiation of health technologies in IP on the ground of the ‘like-product’ analysis deriving from the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1947).4 Chapter 3 will draw into discussion the current implementation of the PA and the structure of risk analysis from international environmental protection. A template for the PA in the international health framework will consequently be developed by means of the philosophical and legal review of the literature on the approach and the examination of relevant international instruments. Chapter 4 will conduct a comprehensive study on the PA applied in existing international legal instruments in the context of health and environment, specifically the International Health Regulations (IHRs),5 the Codex Alimentarius,6 and the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (CPB).7 It is concluded that the implementation of the PA in international law is pervasive, but somehow fragmented and is desperately in need of a clear redefinition in the international public health law regime. In addition to the research of the PA in the health sector, Chapter 4 will also scrutinize its current application in the international trade world, namely the WTO framework. By means of comparative studies on the PA applied in the GATT 1947, the SPS Agreement and the TBT Agreement, this work finds that the current implementation of the PA in the IP regime has been seriously restricted by international political setting. Based on the above analysis, Chapter 5 will suggest that the PA developed in this book be accommodated into the IP regime to promote access to essential medicines. We will then employ the precautionary template developed in Chapter 3 to redefine the compulsory licensing mechanism, and also to assess whether this differentiation of pharmaceutical technologies in compulsory licensing will be in compliance with WTO Members’ (Members’) obligations in WTO law. We will also examine the legal status of the compulsory licensing provision in the WTO framework, and reaffirm states’ precautionary entitlements to grant a compulsory licence in a public health emergency. It is further suggested that the flexibilities in the compulsory licensing clause can be embodied by means of adopting a margin of safety to provide protection in a situation of scientific uncertainty. This leads to a suggestion in Chapter 6 for the introduction of an expedient track to trigger compulsory licensing of pharmaceutical technologies that are strongly associated with the reduction/elimination of risks to human life or health.

1.1.3. Contributions

TRIPS flexibilities that can be used to address public health concerns include provisions relating to objectives and principles, transitional periods for implementation of TRIPS, exhaustion of rights, exceptions to patent rights, and compulsory licences (Matthews 2011: 17). There is existing literature exploring the PA incorporated into domestic patent law prior to the issue of a patent (pre-grant), explicitly through exclusions to patentable subject matter based on five criteria: morality, public policy (or public order), legality, public health and environmental harm (Kolitch 2006: 246; Murphy 2009: 657–8).8 Yet little has been addressed on the PA adopted on issues after a patent is issued (post-grant), specifically related to compulsory licensing.9

The contribution of this book would be to develop a workable procedure to take advantage of applying the PA as the flexibilities in TRIPS that would specifically boost states’ confidence in compulsory licensing, and to safeguard access to medicines in a public health emergency. This rationale developed in this book could also serve as a basis for the moderation of data exclusivity,10 as well as the application to other technologies associated with the reduction of risks to the environment and human health, for example, the patenting strategy for climate change technologies.

1.2. The problem: the clash between IP and the right to health

After the WTO TRIPS entered into force in 1995, when exclusive patent protection for all fields of technology without discrimination became mandatory, debates over the legitimacy of patents for essential medicines and whether it threatens access have reached a climax. Attentions have been drawn to the discussions on the nature of and the limitations on IP. The tension between these two rights has been further evidenced by the extension of the terms and scope of IP and the increasing occurrence of global pandemics, especially in developing and underdeveloped countries, where a security net of a well-established national health system is absent or insufficient.

1.2.1. IP and the right to health

(1) IP as a human right

The right to health and the right to intellectual property are recognized as two distinct human rights enshrined in international human rights instruments. Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) also recognizes such a right in Article 15.1(c). In comparing intellectual property rights (IPRs) against the right to health, the United Nations (UN) Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) distinguishes IPRs from other fundamental, inalienable and universal human rights, including the right to health. It is stated in the General Comment 17 that IPRs are generally of a temporary nature, and may be allocated, limited in time and scope, traded, amended and even forfeited, and can be revoked, licensed or assigned to someone else. The UN CESCR further adopted a statement on human rights and intellectual property which emphasizes that human rights are fundamental as they derive from the human person, whereas IPRs derived from IP systems are instrumental, in that they are a means by which states seek to provide incentives for inventiveness. It is also stressed that traditionally IPRs provide protection to individual authors and inventors; however, they are increasingly focused on protecting business and corporate interests and investments.11 The UN Commission on Human Rights further recognizes that IPRs can provide incentives to stimulate innovation; they can also conflict with, or have adverse implications for, the right to health.12

(2) The right to health

The United Nations Charter states that, based on the principle of equal rights of peoples, the UN should promote ‘higher standards of living’ and ‘solutions of international economic, social, health, and related problems’ (Article 55(a), (b) United Nations Charter 1945). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) provides that ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services’ (Article 25(1) Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UDHR 1948). Further, the ICESCR states that States Parties should achieve the full realization of everyone’s right to enjoy the highest attainable standard of health by taking steps necessary for the prevention, treatment and control of epidemic (Article 12(1) ICESCR).13 It enumerates a number of steps to be taken by States Parties to achieve the full realization of this right, which includes the right to prevention, treatment and control of disease, and the right to health facilities, goods and services (Article 12.2 ICESCR). The right to prevention, treatment and control of disease includes the creation of a system of urgent medical care in emergency situations (Article 12.2(c) ICESCR). The right to health facilities, goods and services includes appropriate treatment of prevalent diseases, and the provision of essential drugs (Article 12.2(d) ICESCR).14

The implementation of the ICESCR is monitored by the CESCR. The Committee specifies ‘Availability, Accessibility, Acceptability, Quality’ as essential components for the fulfilment of the right to health.15 General Comment No. 14 is the official interpretations by the CESCR surrounding the issue of the right to health, which acknowledges a collective right to public health through the modernization of state obligations under Article 12 of the ICESCR.16 It imposes three types of obligations on States Parties with respect to the right to health which includes ‘the obligation to respect, protect and fulfil’.17 Moreover, States Parties also bear international obligations to ensure municipal public health laws comply with their international obligations in relation to Article 12.18 It spells out the core obligations of States Parties including ‘to provide essential drugs, as from time to time defined under the WHO Action Programme on Essential Drugs’ and ‘to adopt and implement a national public health strategy and plan of action, on the basis of epidemiological evidence, addressing the health concerns of the whole population; the strategy and plan of action shall be devised, and periodically reviewed, on the basis of a participatory and transparent process …’.19

The United Nations Millennium Project sets out that improving health and reversing the spread of HIV/AIDS and other major diseases is one of the primary targets of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Providing access to essential drugs in developing countries in cooperation wi...