![]()

1

Sources and Method

Introduction

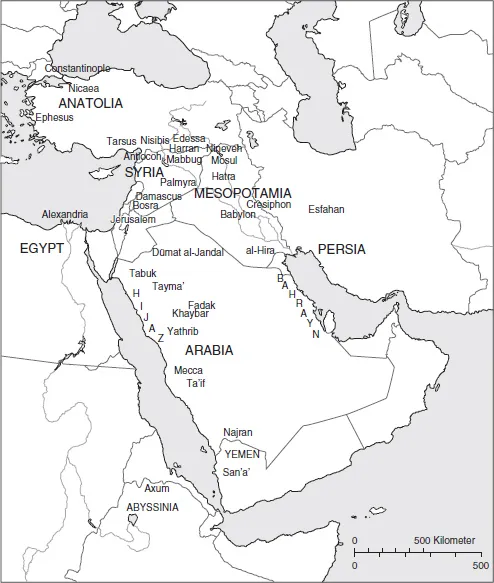

In Yūsuf Zaydān’s bestseller, ‘Azāzīl, the main character quarrels with the demons of his conscience, stating, “Did God create man or vice versa? What do you mean? Each era mankind creates a god of his own predilection, and this god always comes to represent his unreachable hopes and dreams.”1 In the fifth century CE, Hībā was an Egyptian monk whose insecurity about Christian dogma, conscious support for Nestorius (d. 451 CE) before his excommunication, and an affair with a Syrian woman lead him to self-conflict and ultimately tormented him with demonic visions. His conflicted character and the tumultuous days in which he lived leading up to the Church schism in many ways paved the way for the emergence of Islam and the teachings of the Qur’ān. Zaydān, the director of the Manuscript Center at the Bibliotheca Alexandria who spent many years researching a 30-page Syriac manuscript excavated in Aleppo, was finally inspired to write a novel dramatizing the sectarian conflict, dogmatism, and political instability found within the manuscripts which—more importantly—characterized the Near East in the “late antique period” (180–632 CE; see Table 4).2 More specifically, by Near East is meant Arabia, Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Abyssinia, Persia, and Anatolia (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Late Antique Near East

Source: Labeled by Emran El-Badawi (open source)

The late antique Near East—which Islamic tradition came to know as the “jāhiliyyah” or “pre-Islamic World”3—had become accustomed to strong sectarianism and great violence, because imperial powers had merged the functions of religious piety with political life.4 Imperial power was exercised by the two global polities of the day, the Sasanian and the Byzantine empires. As a result of imperial sponsorship Zoroastrian and Christian practices and religious texts became especially widespread throughout the region. This also polarized the Near East into an eastern and western sphere, fueled warfare and gave rise to orthodox (state sponsored) vs. heretical (un-sponsored) forms of religious piety.5 Soon the late antique Near East was transformed into a heated sectarian arena with Zoroastrian, Monophysite (especially West Syrian/Jacobite), East Syrian (Nestorian), Melkite, Sabian-Mandaean, Manichean, Mazdian, Jewish, Jewish-Christian, and pagan groups, all competing for the souls of the faithful.

In the central lands of the Near East, beyond the immediate reach of Byzantium and Ctesiphon and where the Syrian steppe meets the vast and barren Arabian desert, direct imperial control was absent and different peoples lived within highly decentralized or tribal political structures. This fostered a diverse cultural and religious environment relatively free from imperial and orthodox persecution. Therefore, this region provided a safe haven for the development of prominent urban syncretistic pagan cults such as those in Harran, Ṭā’if, and Mecca; the flourishing of large Jewish communities including those in Khaybar, Yathrib, and Ṣ.an‘ā’; and it supported reticent Christian cities including Edessa, al-Ḥīrā, and Najrān. In this region, traditions of popular Christian lore and piety flourished in the Aramaic dialects of Syria-Mesopotamia—Syriac—and that of Palestine, Transjordan, and the Sinai—Christian Palestinian Aramaic. Long standing trade, tribal resettlement and missionary activity expanded Arabia’s heterogeneous cultural and religious activity to include such Aramaic traditions as scripture and liturgy, including hymns, homilies, dialogues, and other such religious treatises.6

Desert hermits encamped in the wilderness, as well as itinerant businessmen like Muḥammad (ca. 570–632 CE) from the aristocratic Quraysh tribe of Mecca, were in constant dialogue with such popular Aramaic Christian impulses passing through the trade routes of Ḥijāz and along the west coast of Arabia. The scripture revealed to him was the Qur’ān, which like scriptures before it legitimated itself through, built itself upon, and responded to heterogeneous religious traditions, contending ideas of a diverse sectarian audience, and heterodox forms of piety. The verses of the Qur’ān portray an environment of heated sectarian conflict and prosletyzation (cf. in relation Bukhārī 6:60:89). This is evident in the text’s discursive references to: believers (mu’minūn) vis à vis Muslims (muslimūn; cf. Q 49:14); assemblies who have splintered and disputed (tafarraqū wa ikhtalafū; 3:105); Jewish groups (al-ladhīn hādū; al-yahūd; banū isrā’īl); Christians (naṣārā); People of the Gospels (ahl al-injīl; Q 5:47); People of the Scripture (ahl al-kitāb); Gentiles (ummiyūn); Sabians (ṣābi’ūn; Q 5:69; 22:17); Magians (majūs; Zoroastrians?; Q 22:17); puritans (ḥunafā’; pagans?; cf. Q 22:31) vis à vis associators (mushrikūn; polytheists?); hypocrites (munāfiqūn), and rebels (kuffār).

We learn that the rebels live in “complacence and factionalism” (‘izzah wa shiqāq; Q 38:2). Furthermore, we learn that among them are “those who say that God is Christ the son of Mary” (Q 5:17, 72) or “the Third of Three” (Q 5:73). Splinter groups existed even among the believers as reference is made to: sects (firaq, sg. firqah/farīq; especially Q 2:75; 146; 100–101; 3:23, 78, 100; 5:70; 19:73; 23:109; 34:20); groups (ṭawā’if, sg. ṭā’ifah; e.g. Q 33:13; 49:9; cf. Q 61:14); units (fi’āt, sg. fi’ah; Q 3:13, 69–72; 4:81; 7:87) and parties (aḥzāb, sg. ḥizb; Q 5:56; 58:18–22). To these may be added the brethren in religion (ikhwān fī al-dīn; Q 9:11) and subjects (mawālī; Q 33:5). Similarly Q 5:48 teaches that different religious groups possessed different laws and customs (shir’ah wa minhāj). The enmity (‘adāwah) of the Jews and the friendliness (mawaddah) of Christians found in Q 5:82 is also worthy of note in this regard. Moreover, Q 60:7–8 cautions the believers that “God may cause friendliness (mawaddah) between [them] and those whom [they] antagonize,” and that they should deal honestly and equitably with “those who have not fought [them] in religion nor expelled [them] from their homes.” The point is that the Qur’ān makes ample refernce to the sectarian landscape from which it emerged.

The prophet Muḥammad sought to bring an end to the sectarianism of his world by calling the People of the Scripture to join him in coming t...