![]()

1

Introduction

The living space in the house I bought in Oxford, England in 1984 is roughly one-third the living space in the house I bought in Lawrenceville, New Jersey in 1980, when I was teaching at Princeton University. I paid about the same amount for each of these houses, in terms both of dollars and income multiples, and although I do not know for certain, I suspect that each is worth about the same, substantially higher, amount today. A housing dollar buys a lot of space in the United States, so much so that comparisons with virtually any other advanced industrial country are bound to make the latter look inferior. Comparisons between the United States and Japan certainly yield this result. In this book, I intend to treat the United States as the exceptional case that it is and to base any comparisons I make on Britain and the rest of Western Europe. I also intend to consider Japan as a whole, rather than concentrating – as so much recent journalism and not a little scholarship have done – on Tokyo.

I like Tokyo a lot. Most of my Japanese friends live in Tokyo or in the surrounding metropolitan area. In terms only of housing and its cost, with no consideration of the many tangible and intangible benefits of life in or near the capital city, they do not live very well, not even by the Western European standards for which I have opted. But just as London is not typical of the housing conditions of Britain, nor Paris of France, so too Tokyo is not typical of Japan. Many people in Japan, including much of the urban population of non-Tokyo Japan, now live in reasonably affordable housing that is in overall size and other quantitative measures roughly comparable to the housing prevailing in Western Europe. Just as America is the exception as far as the rest of the developed world is concerned, so too is Tokyo the exception as far as the rest of Japan is concerned. I will devote a separate chapter to Tokyo, rather than allowing its peculiar circumstances on the housing front to dominate, and skew, the discussion.

Although rural Japan will figure in the discussion from time to time, my main focus will be on the changes in urban (and suburban) housing that have occurred since the end of the Second World War. As in Western (and Eastern) Europe, that conflict caused considerable damage to the existing housing stock, especially in urban areas. Dwellings that were not destroyed in air raids might well have been razed to create air raid defenses. Materials for construction and repair were in increasingly short supply and ultimately ran out. Widespread homelessness, flimsy shantytowns and overcrowding in dilapidated prewar dwellings were the result. Rebuilding the urban housing stock became a major focus of postwar reconstruction, involving both public and private efforts, and – as in Europe – taking far longer than anticipated. Not until 1968 was the goal of one dwelling per household nationwide achieved, and it would be a further five years, until 1973, before that target was reached in prefectures containing the largest cities. The housing crisis (jūtaku nan) was a central feature of daily life for over two decades for millions of Japanese.

The next chapter consists of my translation of a first-hand account of coping with that crisis during the 1960s, published by Kyōko Sasaki in 1971.1 Chapters 3 through 5 will elaborate on some of the issues that flow from her account. In chapter 6 I will discuss housing in Tokyo and its environs, and in a concluding chapter I will make some observations about housing in Japan in the mid- to late 1990s.

It was rather late in my survey of the Japanese literature on postwar housing that I came upon Sasaki-san’s account. I had read dozens of official reports, a massive history sponsored by the high-rise construction industry, many academic studies of postwar land and housing policies, some architectural histories and a few sociological analyses of family and community life in high-density housing estates. However expert this literature may have been, and however significant the issues – and controversies – it revealed, it didn’t deal sufficiently directly with the changing housing experiences and lifestyles of fairly ordinary urban Japanese people that interested me. Here at last was an inside view, written by an observant wife and mother who found herself at the sharp end of housing provision. As a social historian, I had finally found a text that resonated with my concerns.

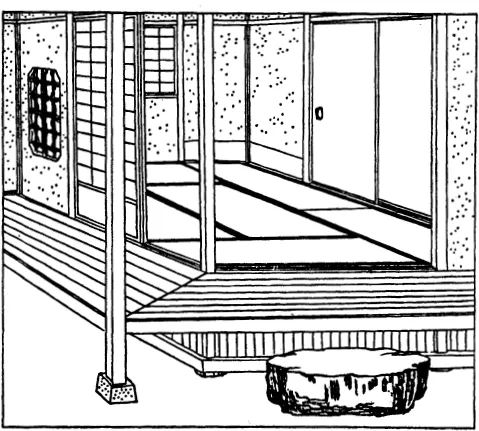

Figure 1.1 A 6-mat room in a traditionally built Japanese house

Source: Jukichi Inouye, Home Life in Tokyo (Tokyo: s.n., 1910), p. 41.

With one exception, the text is accessible to any reader. The “mats” referred to are tatami mats woven of strips of rush on top of a thin layer of packed straw and bound in fabric trim. Each mat measured roughly six feet in length by three feet in width.2 In traditional Japanese architecture, or more precisely in the domestic architecture prevailing from roughly the late 17th-century onward, rooms were measured by the number of mats they contained. The smallest room contained two mats and was thus about six feet square. A three-mat room was nine feet by six. Far more common than a four-mat room was a room with four and one-half mats, with the half mat in the center or at one corner. Such a room would measure nine feet square. Six- and eight-mat rooms were nine by twelve feet and twelve feet square, respectively. Residents sat directly on the mats or on thin cushions placed on them and slept on futon bedding spread out on the mats each night. One mat provided adequate space for one adultsized set of bedding. There were no chairs and very little in the way of other furniture. There will be more about tatami mats and the lifestyle they supported both literally and figuratively later, because one of the most significant – and space-consuming – changes in postwar Japanese housing has been the shift from traditional “floor sitting” to western-style “chair sitting.”

![]()

2

Experiencing the Housing Crisis

by Kyōko Sasaki

1. As newlyweds: from one-room apartment to company house

We were married in March of 1961. It was the year after the massive protests against the US–Japan Security Treaty, and just slightly more than a year after we had graduated from university. Our new home was a 4.5 mat room in an apartment house in the Dōzaka district of Komagome, not far from the center of Tokyo – the very Dōzaka district that has figured from time to time in novels. It was a room I had rented earlier for myself, and since my husband was due to take up a job in another city in May he simply moved in with me.

There were seven one-room apartments in all, originally built for the married employees of a small construction company. At the time, employees of that company and their families occupied four of the apartments, I occupied one, and the remaining two were each occupied by two or three young male high school graduates from outside Tokyo who worked for the same firm as I did. I’ve called this place an apartment house, but in fact all the rooms were located on the floor above the lumber yard and workshops of the construction company. When the company worked Sundays or holidays, the noise from below made it impossible to get any rest. To make matters worse, the building was right next to the incline where streetcars made their way to Tabata and where the roadway was always clogged with traffic. When a big truck went by, the building would tremble as if an earthquake were occurring. “So that’s why this district is called Dōzaka [Moving Slope],” we’d joke.

The kitchen, toilet and drying racks for laundry were communal, and we took turns with the cleaning. It was tacitly assumed that the men would be excused from such duties, I suppose because they were often away on one assignment or another. The cleaning chores did not always go smoothly. Sometimes one of the wives would find that the toilet was particularly dirty when her turn came to clean it and she’d complain to the next person she saw, “I’m sure we have so-and-so to blame for that mess.” Or if the cleaning of, say, the kitchen hadn’t been done just right (equally likely, if someone had come in immediately after a perfect cleaning job and left disorder behind), all sorts of gossip would begin about the failings of “the woman on duty today.” Because there was no laundry room, we had to use the kitchen sink for washing clothes. For those of us like me who worked during the day, that meant waiting until night, after everyone else had finished washing their dinner dishes, to do our laundry. Then we’d have complaints about how the sound of running water prevented the others from falling asleep. As a result of all these difficulties, not even a small group of four or five women could manage to get along in harmony. The couple living next door to us, quiet enough even though they had an infant son who was just beginning to walk, finally gave up and moved out.

The two of us, just a year beyond graduation, found it difficult to shed our student lifestyles. We lived simply, with only a desk, two bookcases, a cupboard for dishes and a low, folding dining table as furniture, falling far short of the prevailing image of the newly married couple. Even when friends came to visit from time to time, we didn’t feel at all self-conscious and concentrated on having a good time. No doubt our optimistic outlook on life was buoyed by the prospect of moving fairly soon and knowing that company housing would await us at our destination.

Looking back on that time, now that I am the mother of three and know something about family life, I simply cannot imagine how any couple could manage in one of those 4.5 mat rooms if they had the usual array of furniture – chest, mirror stand, television set, etc. – not to mention having a child as well.

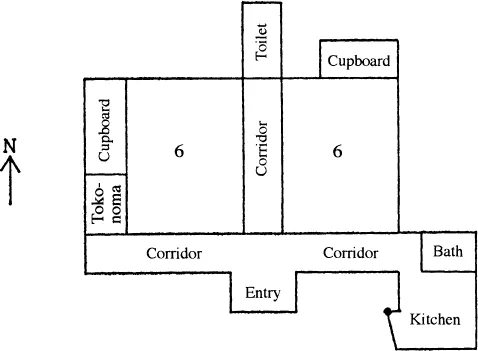

Our new home was in Okayama, on the northern fringe of the city, in a pleasant residential district surrounded by rice paddies and other fields. The house was a detached structure, rented by the company from a private landlord and sub-let to its employees. There were two 6-mat Japanese-style rooms and a kitchen. Originally there had been no bathtub, but the company had had one installed on a concrete floor in a corner of the kitchen. A central corridor ran between the two main rooms, contributing to the sense of spaciousness. The house itself was newly built and more than ample for a married couple.

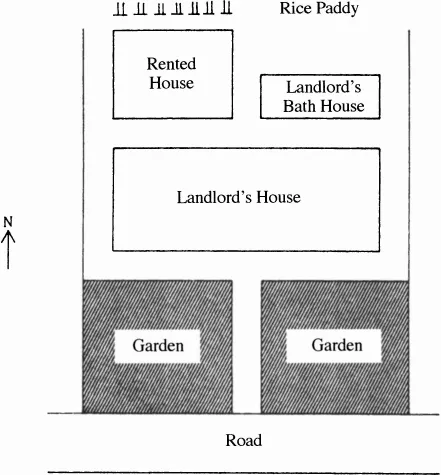

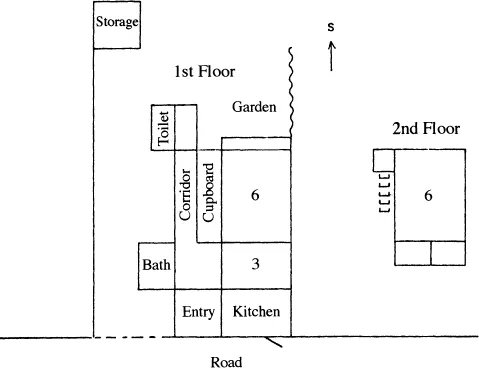

Figure 2.1

However, the location of the house was a problem. Only a little more than six feet separated it from the landlord’s house to the south, and to get to the road we had no choice but to make our way under the deep eaves of the landlord’s roof. When the sliding doors of our house were open, everything inside could be seen from the landlord’s living room, and because of the steep roof of the landlord’s house, little sunlight reached us. What I disliked most was the feeling that the landlord was always sitting just over there, watching everything we did. It bothered me that he could see us coming and going, take note of any guests who came to visit, and observe how we lived.

One Sunday, my husband and I set off to visit some friends who lived nearby, and I left the water running slowly into the bathtub. Normally I would have thought of the money I was wasting on water charges when the tub was filled and began to overflow, but this time I didn’t. When we returned home, the landlord was in an uproar. He must have shouted at us for over an hour. What I hadn’t noticed beforehand was that the house did not have a proper drainage system. Water from the kitchen sink and bathtub merely collected in a small sump outside the house and then seeped into the surrounding ground. The steady stream of water overflowing the tub and escaping through the drain in the floor had soon exceeded the capacity of the sump and flooded the land at the side of the house.

Figure 2.2

I later heard that the landlord had registered the house as a shed in order to evade taxes. This proved very advantageous to us, because rents for company housing were determined on the basis both of the salary of the employee and of the fixed assets tax levied on dwellings (but not, of course, on sheds). At the time, my husband’s salary was somewhat less than the 20,000 yen monthly earned by employees of top companies who were in their second year of work, but I recall that our rent – thanks to the landlord’s tax dodge – was only about 100 yen per month.1

We lived in this house for about a year. Then a house owned by the company became vacant and we moved into it. Our first child had just been born, and we had become a family of three. Our new house had originally been a substantial single-family dwelling, but subsequently it had been divided right down the middle into two units. On our part of the second floor we had a 6-mat room, and on the first floor a 6-mat room, a 3-mat room, kitchen, bathroom and toilet. It was convenient to have an upstairs room, and what a blessing it was to have ample storage: a large closet downstairs and both a small cupboard and a small closet upstairs. There was an open veranda on the south side of the house and a narrow garden with a big storage shed. Now that we were raising a family I was pleased to have a sunny place where children could play.

But what bothered me was that right next door, on the other side of that thin dividing wall, lived people employed by the very same company.

Figure 2.3

Loud voices could easily be overheard, and there was no way of entertaining my own circle of friends without the wife next door noticing. I knew she didn’t mean any harm when she’d ask “And who were those guests who dropped by yesterday?” but it really bothered me nonetheless. And it worried me no end that details of our domestic rows would be made known to all my husband’s colleagues if the husband next door was at all given to talk.

Here we were, just two families living side by side whose husbands worked for the same company. What must the strain be in apartment-style company housing, where large numbers of families live in close proximity? Fights among the children, their good and bad points, which wives get along with the others and which don’t – it is said that matters such as these often become the topics of company gossip. And there are repercussions for the families, too. When ordinary employees and section chiefs live in the same building, the section chiefs are still section chiefs when they get home at night, this affects the pecking order among the wives, and it also has an impact on the children. There may indeed be people who curry favor with the wives of section chiefs in the hope of securing some sort of advantage. On the other hand, even if the wife of any ordinary employee and the wife of a section chief hit it off and become good friends, others will conclude that the wife of the ordinary employee is merely a skillful flatterer. All of this constrains the behavior of the people, especially the wives, who live in large-scale company housing, making for artificial social relations if not stifling sociability altogether.

I know a young housewife who lived for a time in company housing. She had always had a lot of get-up-and-go, and after her marriage she threw herself into participation in a democratic women’s group and in the residents’ association of the building where she lived. A few days after she had taken a petition around the building, her husband was summoned by his supervisor, who told him in a voice dripping with sarcasm, “I hear your esteemed wife is quite the activist.” A male friend of mine who worked for a top company was able to rent superior company housing, but he got so fed up with the constant interference in his private life that he finally moved his family of four into a cramped Japan Hou...