- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geography in the Primary School (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

First published in 1987, this title provides primary school teachers with ideas by which geographical skills and ideas can be introduced in the primary school. John Bale shows how teachers can build on children's 'private geographies' with practical learning strategies, examining approaches to the teaching of map skills, the ways in which the locality can be used and how information about distant places can best be relayed. An interesting, useful and relevant guide, this title will be of particular value for teachers and teachers in training, as well as those studying primary Education more generally.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geography in the Primary School (Routledge Revivals) by John Bale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Young geographers and the worlds inside their heads

The images of the world which children (and adults) carry about inside their heads are derived, on the one hand, from personal experiences of visiting places and, on the other, from vicarious experiences via media of various kinds. This chapter is concerned with establishing the nature of children’s geo-graphical images upon which a geographical education might be constructed and the ways in which these images are represented. In order to understand the sources of these images we will also need to examine children’s spatial behaviour and environmental experiences.

Children travel within their neighbourhoods reasonably frequently. They journey to more distant places less often, grasping and internalising selective images of these places. Such journeys would include visits to relatives, friends and holiday locations. Most geographical images, however, are projected by media such as radio, television, films, comics and books. As Pocock and Hudson (1978, 96) point out:

depite modern mobility, man (sic) is still dependent to a considerable extent on secondary sources for his information of ‘far places’. The cumulative influence of schooling and vicarious experiences through the arts and popular mass media enable him to know, and hold opinions about, many places never actually visited.

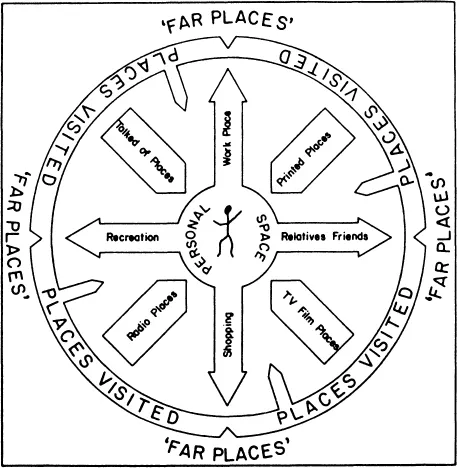

The variety of the information sources from which local, regional and national images are derived is shown in Figure 1.1 Children have reasonably detailed and accurate images of the personal spaces within which they regularly move (i.e. house and home); they possess somewhat less accurate images of local places and much less accurate images of far places. It is these that are most frequently communicated via various media.

The geographical images we carry around with us are therefore the results of a communication process. The image is not only produced – sometimes carefully and with a desired end in view as in the case of propaganda – but also projected. It is then received as a mental map or geographical image. It will be up to the individual teacher, textbook writer, local educational authority or central government to decide if a subsequent stage is required, namely the countering of the image by presenting alternative regional or environmental information.

Later in this chapter we examine some aspects of the mental maps which children have of both local and distant places. However, before doing so it will be worth familiarising ourselves with various dimensions of the geographical behaviour of young people since it is important for teachers who wish to build upon children’s own experiences of the world to appreciate their geographical activity and the ways in which it is influenced and constrained. It is to an initial appreciation of children’s spatial behaviour, which in turn influences their private geographies, that we now turn.

Moving in the locality

In his detailed study of children’s spatial behaviour, Roger Hart (1979) noted that for children aged 5 to 11 in a case study school in a small American town, three generalisations could be made concerning their local movements. The first of these was that the furthest distances children were allowed to go increased between the ages of 5 and 10 but not between 10 and 11. This applied to the distances children were allowed to go without having to ask or tell parents, the furthest they could go with parental permission, and the furthest with other children. Parentally restricted ranges of movement are derived from parents’ fears about children’s safety. Over time mobility increases, not only as a result of increased confidence and trust but also as a result of children’s acquisition of simple vehicles such as bicycles.

Figure 1.1 Sources of information, types of behaviour and environmental images

(Source: Goodey, 1971, 7)

(Source: Goodey, 1971, 7)

A second general finding is that a number of environmental factors seem to influence children’s spatial range. For example, Hart (1979, 72) found that children living in suburban areas tended to have a larger spatial range than children living in towns. One might extend this to suggest that the spatial range of rural children is greater than that of those living in urban environments. Good ‘visual access’, a quiet neighbourhood and a high proportion of children of similar age encourage relatively large amounts of spatial freedom.

A third finding of research into geographies of young children is that significant gender-related differences exist in their spatial behaviour. Hart’s work revealed that whereas the main maximum distance of ‘range with permission’ of girls of 9 to 11 years was 860 metres, that for boys was 1002 metres. More dramatic differences were found for younger children, boys of between 5 and 8 years of age having a mean maximum distance of more than twice that of girls. Similar, though slightly less dramatic, results were found for English primary school children in the city of Coventry (Matthews, 1984, 330) (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Distances of furthest point from home: boys and girls

| Grades/age | Mean of distances of furthest point from home (metres) | |

Boys | Girls | |

grade 1–3a | 244 | 114 |

grade 4–6a | 684 | 283 |

age 6b | 184 | 177 |

age 7b | 272 | 265 |

age 8b | 217 | 210 |

age 9b | 599 | 393 |

age 10b | 613 | 401 |

| age 11b | 1061 | 680 |

(Based on (a) Hart, 1979, 47 and (b) Matthews, 1984, 330)

Such differences are confirmed by Newson and Newson (1968), whose study of 4-year-olds in Nottingham revealed similar results. Their conclusion is that the restricted geographical range of girls results from greater parental fear of molestation than with boys. As the Newsons (1978, 108) observed from a study of 7-year-olds.

by the age of 7, and in a whole variety of ways, the daily experience of little boys in towns of where they are allowed to go, how they spend their time and to what extent they are kept under surveillance is already markedly different from that of little girls.

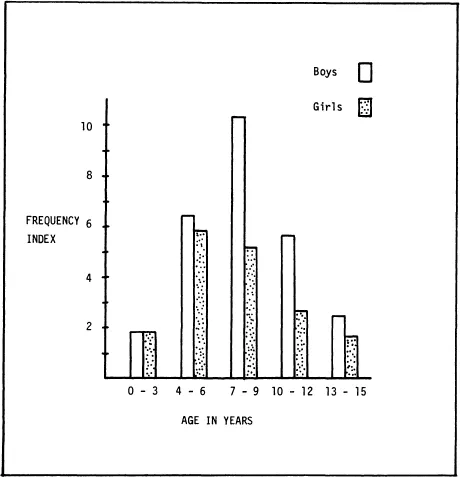

Figure 1.2 Frequency index of children’s outdoor activities in Plankan, Stockholm

(Source: Björklid, 1982, 124)

(Source: Björklid, 1982, 124)

As a result of such differences in mobility boys tend to show ‘an awareness of places further away from their homes than girls’ (Matthews, 1984, 329) though the precise information boys and girls have about the places they visit may not vary significantly. Girls are expected to spend more time indoors and help their mothers about the house. Playing in fields, climbing trees and generally being outdoors is considered more appropriate for boys. A study of children on a Stockholm housing estate (Björklid, 1982) showed that girls spent substantially less time than boys in outdoor activities, the differences being greatest between the ages of 4 and 12 (Figure 1.2).

As Hart (1979, 66) stresses, ‘there is no biological basis for such different behaviors’. Such gender differences are given emphasis here because they may contribute partially towards the subsequent underachievement by girls in map-reading tests, a subject we return to later.

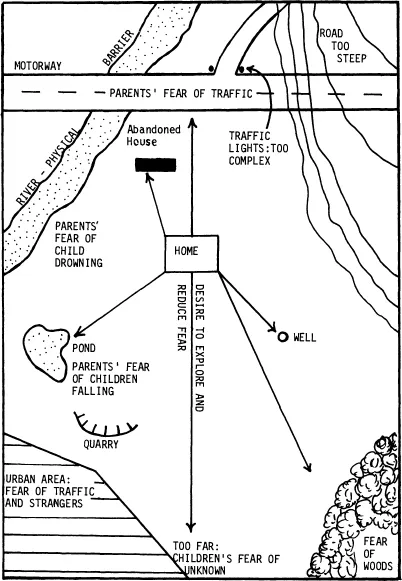

Common factors influencing the primary school child’s spatial behaviour can be summarised in the form of a map (Figure 1.3). It is the immediate locality which the child first explores and which provides stimuli for further exploration and discovery. The locality generates powerful images which reside well into maturity. But within the locality place preferences will emerge. Fields, trees, ponds, playgrounds and streets free from traffic are all places about which children will discover detailed knowledge. On the other hand, dangerous places like quarries, rivers, and motorways, and ‘scary’ places like woods and old houses, are avoided.

The teacher needs to be aware of the spatial characteristics of children’s behaviour because it is upon these foundations, and upon the mental images which they generate, that more formal geographical education will be built. We have looked briefly at the nature of children’s geographical behaviour. Having done so, we can now proceed to an examination of how they represent the world inside their heads.

Representing the locality

Children represent the area most familiar to them as cognitive maps. From birth to about 2 years of age children’s understanding of their environment is entirely egocentric. Piaget and his associates (Piaget and Inhelder, 1956, Piaget et al., 1960) have shown that by the age of about 4 children are beginning to understand the location of objects around them in a topological sense, i.e. in relation to one another. In the infants school children usually view their environment as a series of links and nodes and come to represent this cartographically as a topological cognitive map (Catling, 1978b). This link-picture map is still highly egocentric, with well-known places such as the school or the homes of friends shown as ‘pictures’, all connected to the home. Direction, orientation, and scale are non-existent on such maps (Figure 1.4a).

Figure 1.3 Common forces influencing children’s spatial behaviour (Based on Hart, 1979)

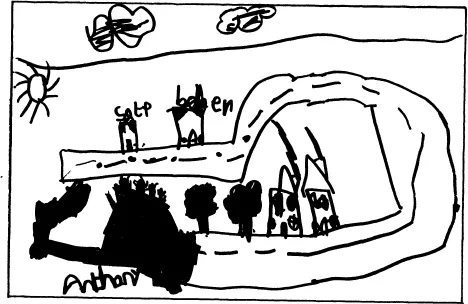

Figure 1.4 Stages in cognitive mapping. The quasi-egocentric and quasi-projective stages occur between the two stages shown

(a) Topological (egocentric) stage. A link-picture map of the village of Betley, Staffs, drawn by a boy of 5 years of age. Known places (countryside, bottom left, shops, top) are connected to home. Direction, scale, orientation and distance are non-existent. The street, drawn in plan form, is rather untypical of this stage

(b) Euclidean (abstract) stage. This accurate and detailed map of the village drawn by the same child at the age of 10 illustrates an abstractly co-ordinated and hierarchically ...

(a) Topological (egocentric) stage. A link-picture map of the village of Betley, Staffs, drawn by a boy of 5 years of age. Known places (countryside, bottom left, shops, top) are connected to home. Direction, scale, orientation and distance are non-existent. The street, drawn in plan form, is rather untypical of this stage

(b) Euclidean (abstract) stage. This accurate and detailed map of the village drawn by the same child at the age of 10 illustrates an abstractly co-ordinated and hierarchically ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Introduction

- 1 Young geographers and the worlds inside their heads

- 2 Aims and objectives

- 3 Teaching map skills

- 4 Using the locality

- 5 Far away places

- 6 Classroom styles

- 7 Towards a geographical education

- 8 Conclusion and on going further

- Bibliography

- Index