![]()

Part I

Logical Foundations

![]()

CHAPTER I

Wittgenstein’s Theory of Meaning

The new logic, developed by Boole, Schroeder, Pierce, Peano, and Frege (to mention only the most important names) was made into a well-organized system by Russell and Whitehead in the Principia Mathematica. A definite logical theory underlies this work. The Principia Mathematica is, nevertheless, incomplete or erroneous in at least three respects. This incompleteness or erroneous character could be explained somewhat paradoxically by saying that (1) there is too much theory, (2) there is not enough theory, and (3) there is no theory whatsoever. There is too much theory in the sense that a purely symbolic system, purporting to be logically autonomous, should not require any verbal or non-formal instruction for its manipulation and should not require any theoretical basis not contained in the formal paraphernalia of the system, whereas Principia must be explained at every step by non-formal instruction and theories, etc. On the other hand, it is no objection, but rather a logical demand, that whatever theory can be formalized within a formal system should be so formalized, and that whatever cannot be formalized should not occur at all within the system. In this sense, Principia does not contain enough theory. Finally, whatever deserves the name of “theory of a formal system” should be organized in a completely articulate manner, such that no part of the theory does not have a well-defined connection with the theory as an organized whole. In this sense Principia has no theory at all.

An axiom which is not formally expressed, but which is integral to

Principia, is the so-called axiom of Extensionality. This axiom states that every function of functions is an extensional function. It is not necessary to inquire whether “function

f is extensional” is an exception to this axiom. The important thing is that the axiom is apparently violated almost at the outset by the introduction of the proposition connecting real and apparent variables. For instance (

x)

ϕx ⊃

ϕu, which is roughly translated as “whatever holds of all, holds of any”, should be an extensional function by the axiom of extensionality. Now (

x)

ϕx is evidently an extensional function of

whereas

ϕu is apparently not an extensional function of the propositional function, since the idea of “any” is equivalent neither to that of “all” nor to that of “this individual one”. The idea of “any”, therefore, has no place in the system, and its introduction indicates the absence of a theory in

Principia.

Again, the theory of types may be considered. A type is the range of significance of all propositional functions which take the same objects as values of their arguments, i.e. of all equivalent functions. The theory, or, better, axiom of types, states: Arguments of a given function are all of the same type. This theory cannot be formulated within the system of Principia because the idea of “any” possible argument of a given function is not an extensional idea. There are other reasons why this idea cannot be formulated, one of which is that constant expressions occurring in mathematical logic are limited to the logical constants, and because “type” is a constant expression, but not a logical constant, it cannot occur in the formal system of Principia. This much for the theoretical difficulties of Principia, considering it solely from the formal point of view.

From the broader standpoint of general philosophy, other difficulties arise which are of greater interest here. The explicit purpose of the Principia was to demonstrate that the concepts and assertions of mathematics are entirely derivable from the concepts and assertions of symbolic logic. From many essays of the authors (particularly Russell), as well as from the fact that certain sections have an especially philosophical interest, it is revealed that another equally important purpose also guided the construction of the Principia. The construction of an exact logical language is to serve in solving philosophical problems and in presenting a complete schematism for representing the structure of the world of science and experience.

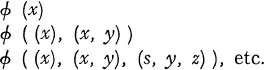

This construction can occur in two ways, each of which stands in subtle opposition to the tenets of Logical Positivism, but seems none the less to be demanded by those tenets. The first method of construction is to introduce the set of forms of all elementary propositions as a complete group of primitive forms of all facts which can occur in science or experience. Thus, if x, y, z … represent the constituents of a fact and Rn represents the component, then the forms of all facts would be illustrated by the following schema:—

R1 (x) “Quality-individual” form

R2 (x, y), “binary” relational form

R3 (x, y, z) “ternary” relational form.

In general:—

Rn (x1 … x), “n-adic” relational form.

From the purely notational point of view this schema could be simplified by treating all forms as classes or as predicates.

Philosophically these schemata are indefensible because they neglect the fundamental distinction between classes and relations. But could not the same criticism be levelled against the treatment of an n-adic and an n+1-adic relation which neglects the fundamental distinction between n-ads and n+1-ads? The difference between two relations with different numbers of terms is not simply the difference of number. On the one hand the whole structure of a fact is different according to the number of constituents of the fact. A general sequence of propositional forms has, therefore, only a notational value, but tells us nothing about the world’s structure. The attempt to set forth all possible forms of propositions is required by Logical Positivism. Its principal instrument of investigation is logic, for logic alone can express the syntax of language. The example above shows that the syntax of language cannot be formulated except from an arbitrary standpoint. On the other hand, this conclusion would seem to follow from the empiricism of Logical Positivism. Only those forms of propositions which have genuine counterparts in the empirical world are to be admitted in the logical schematism of admissible (i.e. significant) concepts.

The second method of construction involves no a priori decision concerning the possible forms of all propositions. The structure of propositions is related to the structure of facts; if new kinds of facts cannot be foreseen, their possible forms cannot be anticipated in discourse. A strict and thorough-going empiricism would have to concede that new kinds of facts cannot be foreseen. The second method, therefore, is simply concerned with the logical treatment of propositional forms already known to have objective counterparts in the empirical world. Logical analysis can, therefore, be applied only to what is already known to be significant, because discovered in the empirical world. Here, logical analysis would, except in a few cases, be superfluous because the genuine value of logical analysis consists in its application to those assertions which have hitherto not been examined. Elimination of pseudo-concepts of science by means of logical analysis seems to demand a schematism of admissible conceptual forms. An empirical criterion of meaning and verity seems to make the construction of such a schematism impossible. This is the problem inherited by Logical Positivism from its empiristic and logistic forbears. The Principia Mathematica seems to favour the construction of a schematism such as has been set out above. Its logical theory, which is only implicit as we have seen, must be altered for the purposes of analysis in the positivistic sense. Wittgenstein’s logical theory may, from this point of view, be conceived as a criticism and alteration of the logical language of Principia Mathematica.

With these remarks I shall proceed to develop the logical theory of Wittgenstein.

I

The fundamental characteristic of Wittgenstein’s philosophy is the relationship which he attempts to establish between language and the world. By language, in this usage, is meant the totality of significant assertions (as contrasted, e.g., with language as used in the emotive sense). The totality of significant propositions is related to the totality of objectives of those assertions, and this is the world. “The world” is thus a phrase with a denotation but without connotation.

Wittgenstein calls the objectives of significant assertions “facts”. Facts are what make propositions true, or, alternatively, propositions assert the existence or non-existence of facts. Since facts are the fundamental parts of the world, it would be impossible to define “fact” without circularity. A fact may be described as a combination of objects. This differs from the Aristotelian conception of fact only in so far as a fact may be of any conceivable structure in Wittgenstein’s philosophy, whereas any Aristotelian philosophy (for metaphysical reasons) limits facts to the “inherence of something in something else”. An object is whatever can occur as the constituent of a fact. Now, if facts are taken as fundamental, and hence indefinable, an object could be variously defined. (a) It may be defined as the set of facts in which it occurs, i.e. as the set of facts which possess at least one feature of absolute similarity to one another. For example, the facts of “blue colouring the sky at time t0”and of “blue colouring this book at time tn” have one feature, “blue,” of absolute similarity. (b) Or an object can be defined as whatever is a distinguishable element of a fact. Thus, by exhaustively enumerating all the distinguishable elements constituting a fact, it is possible to isolate all the objects composing the fact in question.

The fact is an independent entity, for whatever dependence may mean in the strictly logical sense, it is reserved for objects, i.e. for entities obviously requiring completion. Facts, being self-sufficient, require...