![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

Chapter 1

David Tuckett

Introduction

It is now some years since the official bodies that control medical education in the UK recommended that all medical students should pursue studies of sociology (General Medical Council, 1967: 15; Royal Commission on Medical Education, 1968: 104–9). Over the last few years it has become commonplace for these students, as well as for many doctors with long experience in clinical work, to take some kind of sociology course. Yet to many of those required to follow sociology courses, and indeed to many of those who have required students to do sociology, the subject is something of an obscure mystery – often considered to have some relationship to socialism or to social work. In this chapter I want to consider some of the features of present-day medical practice that have led to the inclusion of sociology as a useful preparatory discipline and then go on to introduce some of the sociological concepts I consider salient to medical practitioners. Finally, I will review some of the issues in medical practice that I believe can be illuminated by sociology.

But first I should issue a warning: in some respects sociology may be frustrating to the would-be practitioner. Whereas the medical student, particularly at an early stage of his career, wants cut and dried answers, recommendations, and solutions, he will find that the sociologists writing in this book seem to provide only questions, complications, and ways of looking at medical practice. In this respect the sociologist’s approach may be rather different from those he experiences in many other subjects. Nonetheless, I believe it to be profoundly useful. Through greater sociological understanding many clinical judgments may be made more rationally; much of the frustration in present-day practice may be overcome; the behaviour of patients, of colleagues, and of large organizations may be better appreciated; and the doctor may be able to exercise the therapeutic skills he has learnt in other parts of his training more effectively for the benefit of his patients. Wherever possible, the authors will try to indicate how we think sociology can be useful. But inevitably clinical practice consists of individual cases and each doctor has to learn how to use sociology to his own, and to his patients’, advantage – just as he must decide how to apply the other knowledge he has gained in his training.

Some Changes in Medical Problems and Medical Practice

There are about 55,000 doctors employed in the National Health Service. About half of these doctors work in the community – the majority as general practitioners, but a few in the administration of the health, education, and social services, and a few more in industrial settings. About 11,000 doctors work as consultants providing specialist medical care in NHS hospitals, and about 19,000 others assist them as ‘junior hospital doctors’ in various stages of their apprenticeship (although not all such doctors ultimately become consultants) (Department of Health and Social Security, 1974a: 28).

Up to the present, regardless of the specialty or part of the health service that they will eventually work in, all doctors have a common undergraduate training. To a large extent this training concentrates on providing students with the basic scientific knowledge and clinical experience to diagnose quickly and accurately acute life-threatening disease. A student learns to recognize the signs and symptoms of those diseases for which medical science has an available treatment – the infectious diseases, acute appendicitis, trauma, some cancers, and so on. There is an obvious logic to this emphasis in training: when a student starts to practice without supervision the failure to recognize the appropriate signs and symptoms of acute, life-threatening disease would be immediately and unnecessarily fatal to his patients.

But an analysis of the types of conditions that doctors are now called upon to treat – whether in the hospital or as a general practitioner in the community – suggests that this kind of acute life-threatening illness, and the emphasis on speed and accurate diagnosis which it necessitates, is no longer a major part of most doctors’ work. The very success of medical technology – notably the development of antibiotics, and the still more significant advances of preventative medicine – coupled with the rise in living standards, has dramatically reduced the significance of infectious disease. Smallpox, for example, was once the major killing disease. Now, in almost every country in the world, it is an unusual event and is seldom fatal. The present pattern of disease means that doctors are now mainly called upon to treat conditions that prevent individuals from performing self-supporting activities or from developing the intellectual and physical potentialities needed to achieve an inner sense of well-being – that is, conditions like chronic rheumatism and arthritis, chronic bronchitis, diabetes, epilepsy, anaemia, multiple sclerosis, and various forms of mental ‘difficulties’. With these kinds of diseases the main danger is not that inadequate practice on the part of the doctor will lead to the patient’s death, but that it will lead to unnecessary suffering, discontent, inconvenience, or humiliation. Furthermore, since modern medical techniques often keep alive a patient who in earlier times might have died, the doctor now has to help a patient react to and cope with the handicaps that the onset of a condition may impose. [1]

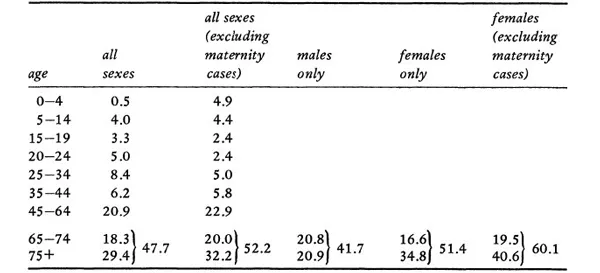

An analysis of the usage of English hospital beds in 1972 gives some indication of the type of conditions doctors are now called upon to treat. Table 1, for example, shows how 30 per cent of all beds in non-psychiatric hospitals are taken up by individuals aged over seventy-five and that 50 per cent of all beds are taken up by individuals over sixty-five. If we look at female patients alone, and exclude those in hospital for maternity care, we find that nearly two thirds of all beds are taken up by individuals over sixty-five. The conditions that these older age groups suffer from are very largely of the degenerative chronic type – quite different to the acute, life-threatening disease of the past.

Table 1 Percentage of beds occupied in non-psychiatric hospitals in England by different age groups

Source: Specially compiled by Dr John Ashley (of the London School of Hygiene) from information supplied by the DHSS in 1-patient enquiry (DHSS, 1974b). (See Klein and Ashley, 1972.)

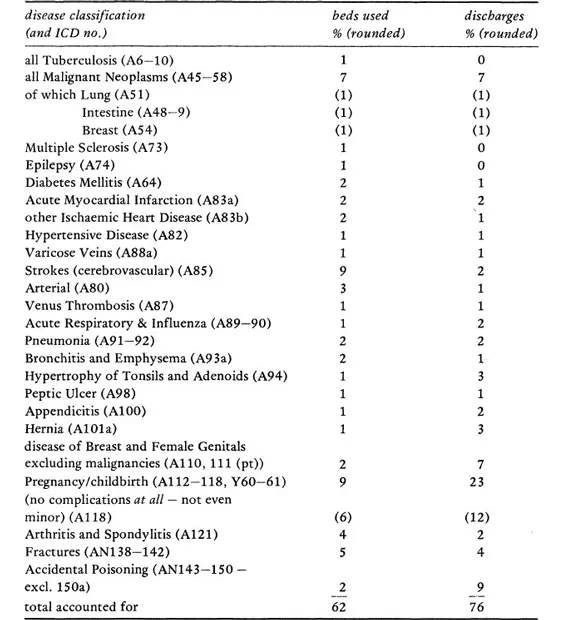

The department of Health’s Hospital In-Patient Enquiry (1974b) provides details of a bed-census carried out in all English non-psychiatric hospitals in 1972. Table 2 provides information on the most frequent diagnoses given on patients in hospital in 1972. The left-hand column gives a picture of the hospital population at any one moment – the individuals you could encounter in a walk around hospitals on an average day – and the right-hand column shows the number of discharges or deaths. Where there are differences these reflect the length of stay required for different conditions. From the table it can be seen that the major categories in terms of bed occupancy are: malignant neoplasus (7 per cent); strokes (9 per cent); arterial disease (3 per cent); childbirth (9 per cent); arthritis (4 per cent); and fractures (5 per cent). The great majority of these conditions are ones which have long-term implications for treatment and management. Infectious diseases, it will be noted, hardly figure at all.

Table 2 Bed occupancy and admissions in non-psychiatric hospitals in England 1972* (All conditions over 1%)

(Source: DHSS, 197413: Table 6)

* I am grateful to Dr John Ashley of the London School of Hygiene for help and advice in the preparation of this table.

All the figures reported above refer to non-psychiatric hospitals, which themselves account for about half of all hospital beds. The number of psychiatric beds, therefore, is very large. The age distribution for psychiatric bed usage is very similar to that in non-psychiatric hospitals and the vast majority of psychiatric in-patients fall into the chronic category – patients whose conditions are treated and managed, in and out of hospital, over long periods of time. About one third of all psychiatric beds are taken up by patients who are mentally subnormal or mentally handicapped, while the remaining two thirds are taken up by patients suffering from some form of ‘mental’ illness (DHSS, 1974a: 152 and 127).

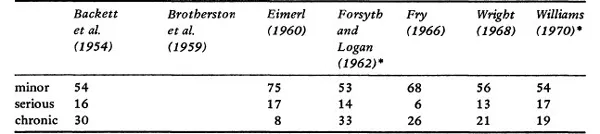

The picture is even more clear in general practice. The average general practitioner with 2,500 patients on his list will spend between 6–17 percent of his time dealing with acutely ‘serious’ disease of a life-threatening variety. He will spend somewhere between 51/77 per cent of his time treating ‘minor’ diseases and between 8–30 per cent of his time managing ‘chronic’ complaints (Backett et al., 1954; Brotherston et al., 1959; Eimerl, 1960; Fry, 1966; Wright, 1968; Williams, 1970). The types of disease that the general practitioner sees in the various categories are set out in Tables 3–6.

Table 3 Estimates of severity of disorders seen in general practice expressed as percentages of total consultations

Source: Royal College of General Practitioners (1973: 19)

* adapted: recorded under physiological, trivial, acute serious, acute non-serious, chronic serious, and chronic non-serious

Table 4 Acute major illness (life-threatening)

illness | persons consulting |

pneumonia and acute | per year |

bronchitis | 50 |

acute myocardial | |

infarction | 7 |

acute appendicitis | 5 |

All new cancers | |

lung | 1–2 per year |

breast | 1 per year |

large bowel | 2 every 3 years |

stomach | 1 every 2 years |

bladder | 1 every 3 years |

cervix | 1 every 3 years |

pancreas | 1 every 4 years |

ovary | 1 every 5 years |

oesophagus | 1 every 7 years |

brain | 1 every 10 years |

uterine body | 1 every 12 years |

lymphadenoma | 1 every 15 years |

thyroid | 1 every 20 years |

severe depression | 12 |

suicide | 1 every 4 years |

attempted suicide | 2 every year |

acute glaucoma | 1 |

acute strokes | 5 |

killed in road accident | 1 every 3 years |

Table 5 Minor illness (of short duration and minimal disability)

illness | persons consulting |

upper respiratory infections | 500 |

common gastrointestinal ’infections and dyspepsias’ | 250 |

skin disorders | 225 |

emotional disorders | 200 |

acute otitis media | 50 |

wax in external meatus | 50 |

‘acute back’ symptoms | 50 |

migraine | 30 |

hay fever | 25 |

acute urinary infections | 50 |

Table 6 Chronic illnesses

illness | persons consulting |

chronic rheumatism | 100 |

rheumatoid arthritis | 10 |

chronic mental illness | 55 |

severe subnormality | 5 |

educationally subnormal | 3* |

vulnerable adults | 40 |

child guidance | 4* |

chronic bronchitis | 50 |

anaemia | 40 |

pernicious anaemia | 2 |

hypertension | 25 |

asthma | 25 |

peptic ulcer | 25 |

strokes | 15 |

epilepsy | 10 |

diabetes | 10 |

Parkinsonism | 3 |

multiple sclerosis | 2 |

pulmonary tuberculosis | 2 |

chronic pyelonephritis | 1 |

* persons attending school or clinic

From these tables it can be seen that the ‘real’ disease of medical school education is quite rare – a GP, for example, only sees a case of lung cancer, the second most common form of death in the UK, once or twice a year. Even acute myocardial infarction will only be encountered about seven times. To summarize, the great majority of the cases the GP sees are either ‘trivial’ or ‘minor’ in a medical sense and tend to be chronic either in their course or in their implications. Myocardial infarction, for example, although acute in its course, has long-term implications for the patient’s life and medical management. As a result, therefore, of present patterns of health and disease or, more strictly, patterns of the demand of individuals for the doctor’s help, today’s practicing doctors, both in hospital and in general practice, are as often concerned with the long-term management as they are with the immediate cure of disease.

In modern conditions the management of disease is infrequently a matter of the indiv...