- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

To Lhasa In Disguise

About this book

First published in 2004. A secret traveller to the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, the author of this unusual volume was forced to live, dress and behave as a Tibetan in order to remain undetected. Because of his unique perspective, he is able to provide an excellent description of the diplomatic, political, military and industrial situation of the country in the 1920s. His account of life in the Forbidden City of the Buddhas contains a wealth of compelling stories and fascinating information.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access To Lhasa In Disguise by William Montgomery Mcgovern in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

To Lhasa in Disguise

Chapter I

Tibet and the Tibetans

FOR many years Tibet has been the mysterious unknown country, and Lhasa, its capital, the Forbidden City of the Buddhas, into which entrance by adventurous explorers was sought in vain.

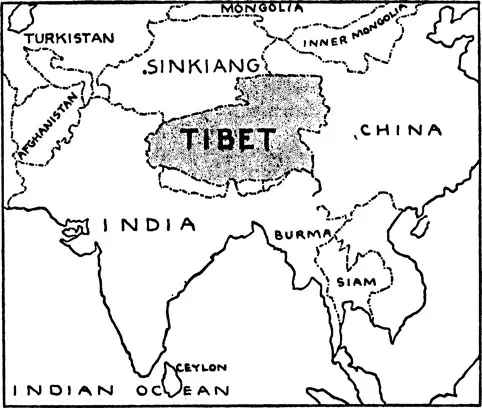

Both nature and the inhabitants have co-operated to make entry into the country well nigh impossible. A huge tableland, whose average altitude is 15,000 feet above sea-level, as high as the summit of Mont Blanc, the highest peak of Europe, it is surrounded and intersected by even greater mountains, many of them over 20,000 feet high, shrouded in perpetual ice and snow.

Tibet has an area of over one million square miles, but though it lies between the two fertile countries of India and China, so bleak and so cold is it that nearly the whole land is a desert devoid of trees and plants, producing only patches of sparse grass which serve to support the deer, the wild ass, the yak, and herds of cattle and sheep. Barley, a hardy plant, is the one cereal grown, and even this flourishes only in the milder parts; but hidden within the ample bosom of this arid land are vast, and almost untouched, stores of natural mineral wealth.

Scattered over this huge territory are groups of natives fiercely jealous of every intruder. Many of them are nomads moving here and there with their flocks. Others form communities dwelling in settled villages. Nearer the larger towns, perched on high hills or precipitous cliffs, are to be found gigantic stone castles, of quaint old-world design, which frown upon the countryside.

Even more numerous than the castles are the monasteries, for Tibet is the country of monks. One man out of every four is a priest, and such persons dwell together in vast buildings placed far away from other habitation. But such institutions, instead of being havens of peace, are the centres of turmoil. Many of their inhabitants become what are known as fighting monks and spend their time in brawling.

Wild, reckless men they are. Sometimes one monastery will wage war against another, and sometimes these ecclesiastical swashbucklers will pour into the towns, and seize and hack to pieces some unpopular governor. The monasteries, having hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of inhabitants, overawe the districts in which they are placed.

It is the monks who are fiercest in hatred of outsiders; it is they who present the greatest danger to the would-be explorer of the inhabited portion of Tibet, for in their foreigner-hating zeal they are apt to ignore any safe-conduct which might be granted by the civil authorities to a stranger.

In the very heart of this gloomy land is the sacred city of Lhasa. Here lives the Dalai Lama, who is both the Emperor and the High Priest of his people, who regard him as an incarnate god. In his magnificent palace, the Potala, he dwells on public occasions surrounded with all the pomp that befits a living deity, and receives in audience the pilgrims who come from every part of Tibet to bring rich offerings and to adore.

He who would seek to penetrate into Lhasa must first overcome the tremendous physical difficulties which bar the way to the threshold of Tibet, and even if he rise victorious over ice and snow, gnarled crag and precipitous cliff, he finds upon arrival on the plateau an angry populace which bars the way and insists on an immediate return.

In the old days various well-known explorers tried, by means of devious routes and various disguises, to escape being turned back at the frontier, and some, indeed, succeeded in passing far into the interior, but only to find that sooner or later, before reaching Lhasa, the abode of the Gods, that they were detected and further progress barred, Among the most noteworthy of these explorers were the Swede, Sven Hedin, and the illustrious American scholar, W. W. Rockhill.

In the last few years a few have been more fortunate. Sir Francis Younghusband, Sir Charles Bell, and General Pereira, for example, penetrating to the goal, have been able to throw a great deal of light upon many hitherto unknown aspects of Central Tibetan life. The Younghusband military expedition of 1904 to Tibet, particularly, was destined to alter greatly the internal history of the country. But in each case the torchlight which illuminated for a moment the Tibetan darkness has been extinguished, and once again and, in fact, more than ever is Tibet the mysterious unknown country and Lhasa the Forbidden City of the Buddhas.

In recent years both country and capital have become more particularly worthy of study, owing to the curious developments which have taken place there. While retaining the glamour of mystery which belongs to a country ruled by monks, many of whom are worshipped as gods, a country which shuts the door on all intruders from without, it is now worthy of the interest of the student of diplomacy, politics, and economics.

We are all aware of the extraordinary transformation which Japan underwent during the course of the latter part of the last century, when from a quaint kingdom of fable, closed to the outside world, it became a first-class modem power, with all the equipment and organization of the West.

A similar transforming movement is now taking place in Tibet—a movement which may have an important influence upon the political future of Eastern Asia. Until 1912 Tibet was a vassal of China, without a standing army or adequate munitions of war. To-day the Chinese have been expelled, and Tibet stands alone and independent. She has a new army, an army ever growing in numbers, well drilled, well disciplined, and armed with rifles, either imported from Europe or made in the Lhasa arsenal. Regular postal communications have been opened between the principal towns, and Lhasa itself is possessed of telephone and telegraph, quaint and crude to be sure, but workable; and that last instance of modem European culture, paper money, is now being printed.

The government has also undergone considerable development. The Dalai Lama, the Supreme Pontiff of Tibetan Buddhism, is now in fact, as his predecessors were in name, the absolute ruler of the country. Tibet has long been possessed of two curious bodies, a council of shapés or secretaries of state, constituting a cabinet, and a Tsongdu, or National Assembly, the Tibetan Parliament or Congress; but in the last decade both these bodies have undergone an interesting evolution, making them correspond more closely to their European counterparts, and even in distant Tibet constitutional crises are by no means unknown. What is most curious is that these modem movements seem to have had no effect in rendering Tibet less exclusive—in fact, in some ways the ring grows tighter. In previous years the Chinese at least were admitted to Lhasa, and now even these are excluded. The new institutions, such as the post and the telegraph, are employed as the most efficient means of keeping the European intruder out, as in this way constant communication between the frontier and the capital is ensured.

To the adventurer and the explorer, therefore, Tibet at the present moment presents a fascinating field of research. In my own case I was equally interested by Tibet as the luring past, and as the womb of the unborn to-morrow. As an anthropologist I became fascinated by the Tibetan people, with their customs, their language, their religion, and their literature. All of these are in some way unique. As one who had studied some of the modem developments in diplomacy and statecraft in the other countries of the East, I was anxious to study the changing institutions of this hidden, theocratic empire, and to see what effect these developments might have upon the relations of the surrounding peoples.

In bygone years I had devoted much time to a theoretical study of the Tibetan language and customs, in the hope that this would the better enable me to carry on exploration at first hand. But it was my privilege to utilize this stored-up knowledge and to continue my studies under very peculiar conditions. Circumstances forced me to cross an 18,000-feet pass into Tibet in mid-winter, at a time when it was blocked with snow and supposedly closed to all travellers, even natives. Arrived in Tibet, I had necessarily to disguise myself as a Tibetan coolie, and to travel as such through the heart of the country. During the latter part of this secret journey the Tibetan Government learned of my escapade and ordered a sharp watch to be kept for me at all the villages. The caravan with which I was travelling, in the humble capacity of servant, was several times stopped and examined without my being discovered.

At last I arrived in Lhasa. Here I was foolish enough to reveal myself voluntarily to the authorities, with the result that the monks in Lhasa led a popular riot against me, and the civil Government, in an attempt to protect my person, was forced to declare me a prisoner of state until the popular clamour had subsided.

After a six weeks’ stay in Lhasa, I was permitted to return to India, an escort being given me in order to ensure my safety. In this way my adventure came to an end, but in the meantime I had been able to secure numerous priceless manuscripts, had met or seen all the principal persons in the sacred city, and had had unequalled opportunities for studying the inner life of the Tibetan people and the working of their institutions.

Chapter II

The First Attempt

THE journey which was destined to have this adventurous end started in a much more conventional fashion. It was, in fact, but the sequel to an earlier open expedition by a party, consisting of five Europeans engaged on scientific research, which penetrated one hundred and fifty miles inside the Tibetan frontier, and managed to acquire a great deal of scientific material before it was stopped and turned back by the order of the Tibetan authorities. It was only through this expedition, of which I was a member, that I gained the necessary experience and information to enable me to carry out my journey in disguise, so that it is necessary in the first place to give a short account of this first attempt to reach the Forbidden City.

In 1921 Mr. George Knight, F.R.G.S., conceived the idea of organizing a research mission to Tibet to carry out a thorough survey of the country and the people.

It was first of all necessary to get in touch with someone who was in a position to organize and finance such an expedition. After several disheartening failures to secure such support, Mr. Knight obtained the hearty co-operation of Mr. William Dederich, F.R.G.S., who was a friend of the late Sir Ernest Shackleton, and who had rendered that great explorer practical help in the organization of Shackleton’s 1914 Antarctic expedition. Mr. Dederich is not only a generous patron of scientific exploration, but a man whose administrative ability renders him of great assistance to an expedition faced with the complicated problems of equipment and organization. By his aid the idea was soon placed on a stable basis and active steps could be taken towards sending out the exploring party.

At first the personnel of the new expedition consisted of four persons, viz. Mr. G. Knight, the leader, who was also to look after botanical and zoological research; Captain J. E. Ellam, the co-leader, who was to devote himself to the study of the political and religious institutions of the country; Mr. Frederic Fletcher, who was to act as geologist and also transport officer to the party; and finally Mr. William Harcourt, who was appointed cinematographer, for it was realized that in modem times a living pictorial record of the land and the people should be an integral part of every scientific expedition.

At a somewhat later period—in fact, only a short time before the date fixed for departure—I was asked to join the mission as general adviser, as it was thought that my previous residence in the Orient and my knowledge of the Tibetan language and customs might prove useful. Through the kindness of Sir E. Denison Ross I was able to secure leave of absence from my University, and was thus enabled to accept the invitation.

We had then to decide upon the direction by which Tibet was to be entered. Three places at once suggested themselves. One was to advance from the east through China. Another was to go from the west through Kashmir and Northern India. The third was to start from Darjeeling, and to pass through the small semi-independent state of Sikkim, which lies between the larger countries of Nepal and Bhutan, and over the Himalayas into Tibet proper.

This last was the route eventually selected, because it would bring the expedition into immediate contact with the central portion of Tibet and with its two great cities, Shigatsé and Lhasa. This route was the more preferable because, as a result of the Younghusband expedition, the Indian Government had secured the right to send certain specially-selected persons to two places inside of Tibet itself. The first of these places was the town of Yatung in the Chumbi Valley, just inside the Tibetan frontier. The other was the city of Gyangtsé, a hundred and fifty miles in the interior. Persons permitted to travel to either place were required to go in a direct line, without deviating in any way from the main trade-route.

The India Office and the Government of India were approached on the subject, and after some negotiation gave us the necessary permission to travel to Gyangtsé, there to apply to the Tibetan Government for further permission to proceed to Lhasa and other portions of the interior, but refused to give us any further support or recognition.

In July 1922 the party set sail for India. It was found impossible for all the members to go out together, so it was agreed to make Darjeeling our rendezvous. Fletcher and Harcourt, however, accompanied me on the s.s. Nellore, and after touching at Malta, Port Said, Colombo, and Madras, we arrived at Calcutta in the middle of August. It was then, of course, the height of the Indian summer, and on many occasions the thermometer registered 110° in the shade.

I have always had a fondness for tropical heat, but my companions suffered so much from it that, after collecting the boxes which had been sent out from England and making a number of further purchases necessary for camp life in Tibet, we went by rail to Darjeeling, where before long the whole of our party assembled.

Darjeeling lies on an outer spur of the great Himalayan range. It is over 7,000 feet above sea-level, and even in summer is delightfully cool. For this reason it was made the summer capital of the province of Bengal: Calcutta, of course, being the winter capital. The chief objection to Darjeeling is its great rainfall, most of which occurs during the summer months, which is the period of the rainy season all over India.

Sixty years ago Darjeeling (properly Dorjeling—the Temple of the Thunderbolt!) consisted of an insignificant village, forming part of the territory seized by the British Indian Government from the little independent hill state of Sikkim by way of reparations. Reparations in those days seem to have been a matter more easily and quickly settled than now!

Darjeeling has had a very rapid development and is now a flourishing city. A large portion of the land seized along with Darjeeling, land which is known as British Sikkim, is laid out in tea plantations, supervised by Europeans, who use Darjeeling as their supply base and frequently ride in for dances and other festivities: their club, the Planters’ Club, is a very important institution.

Apart from these, the resident European population is very small. The more important officials of the Bengal Government have villas scattered along the hillsides, but these are occupied chiefly in summer, at which time the hotels and boardinghouses are also packed with visitors. The native population is much larger and is more permanent.

The great Darjeeling market-square is the famous meeting-place for people of every race and caste. There is a substratum of the old Sikkimese population. Sikkimese are really Tibetans who, in comparatively modem times, have migrated and settled south of the Himalayas. They have kept the appearance, the language, and the religion of their Tibetan ancestors, and for their benefit there are three Lama (Tibetan Buddhist) monasteries in the neighbourhood of the city. In recent years numerous settlers have arrived from the Indian plains. These, of course, axe either Hindus or Mohammedans, and for their benefit there have been erected a Hindu temple and a mosque in the heart of the city.

An even larger number of people come from without the bounds of British India. These include immigrants from the still independent parts of Sikkim, and from Bhutan, Nepal, and Tibet. Tibetans are to be seen all over the town and attract a good deal of attention from the tourists. Many of them have brought down curios from their native lands which are sold at enormous profit to European visitors.

Our party stayed for some three weeks at the Labyrinth, a small residential hotel, and it required all of this time to complete our preparations. Knight and the other members of the expedition frequently visited the market-place in order to secure those supplies which had not been procured in either England or Calcutta.

I, for the most part, was en...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Chapter I: Tibet and the Tibetans

- Chapter II: The First Attempt

- Chapter III: British Influence in Sikkim

- Chapter IV: On the Trade-Route

- Chapter V: Gyangtsé : A British Outpost

- Chapter VI: Preparations for the New Attempt

- Chapter VII: From Jungle to Glacier

- Chapter VIII: Trapped in the Passes

- Chapter IX: “Victory to the Gods!”

- Chapter X: The Disguise Tested

- Chapter XI: Provincial Government

- Chapter XII: Life on the Plains

- Chapter XIII: On to Shigatsé

- Chapter XIV: The Road of Enchantment

- Chapter XV: Shigatsé Onward

- Chapter XVI: Along the Brahmaputra

- Chapter XVII: Gossip and Customs

- Chapter XVIIII: Into the Lion’s Mouth

- Chapter XIX: Running the Gauntlet

- Chapter XX: The Goal in Sight

- Chapter XXI: Exposed!

- Chapter XXII: The Strong Man of Tibet

- Chapter XXIII: Before the City Magistrates

- Chapter XXIV: Secret Meeting with Dalai Lama

- Chapter XXV: Modernising Lhasa

- Index