- 174 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Czechoslovak Economy 1918-1980 (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

Originally published in 1988, this book assesses social and economic change against the background of the international economy and the dramatic political events of the twentieth century - the break up of the Habsburg Monarchy, the Peace Treaty of Versailles, the Munich Agreement of 1938 and the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, the occupation by Nazi Germany, the attempt to reconstruct a democratic Republic, the period of Stalinism and the 'Prague Spring' of 1968. Thus the book produces a balanced historical outline of the economy of Czechoslovakia between 1918 and 1980.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Czechoslovak Economy 1918-1980 (Routledge Revivals) by Alice Teichova in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Czechoslovakia, 1918–45

1

Population

Structure and Growth

According to the first census carried out in the newly formed Republic of Czechoslovakia (ČSR) in 1921, the state had a population of 13,612,424 and covered an area of 140,519 square kilometres. For the development of an independent economy within the boundaries of this Successor State, it was of major significance that, despite only encompassing a fifth of the total area and a quarter of the inhabitants of the former Habsburg monarchy, it contained much more than half of Austria-Hungary’s industrial potential and just under half of the workers who had been employed in the empire’s industry.

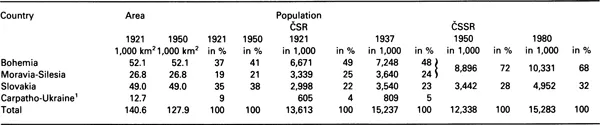

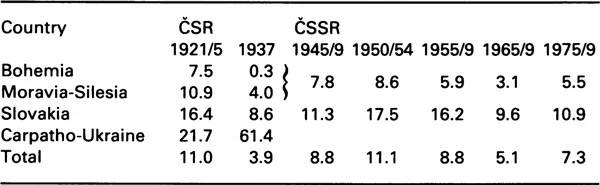

Between 1921 and 1937, the last complete year in the statistical series of the First Republic, the population grew from 13.6 to 15.2 million. This population growth had differing effects on the four national parts of the state (see Table 1.1). The western part — the Czech part (also known as the Historical Lands) — was made up of Bohemia, which covered 37 per cent of the area of the entire nation with a population that fell from 49 per cent in 1921 to 47.5 per cent in 1937, and Moravia and Silesia which spread over some 19 per cent and the population of which dropped slightly from 24.5 per cent to 24 per cent. Slovakia took in an area of 35 per cent and the number of its inhabitants increased from 22 per cent to 23.2 per cent. The eastern part of the republic, Carpatho-Ukraine, covered 9 per cent of the total area and its population grew from 4.5 per cent to 5.3 per cent. The general fall in the growth rate from 10.96 to 3.94 per 1,000 inhabitants shown in Table 1.2 reflected the overall European trend, whereby the natural growth-rate increased relatively in percentage terms from north–west to south-east. However, the rate of population growth in Czechoslovakia differed from the overall pattern in that its rate of increase of 11 per cent during the interwar years was far below the European average of approximately 20 per cent, whereas the increase in the population of the South-east European nations was significantly above this average.

Table 1.1: Area and population of Czechoslovakia, 1921–80

1 Until 1938 Subcarpathian Russia (Ruthenia).

Sources: Censuses of the State Statistical Office in Prague, 1921 and 1950; Vývoj společnosti v číslech (Social development in numbers) (Prague, 1965); relevant years of Statistická ročenka ČSR and Československá statistika (Statistical Yearbook ČSR and Czechoslovak Statistics) (official publication of the state, later Federal Statistical Office).

Table 1.2: Population growth in Czechoslovakia, 1921/5–1975/9 (in %)

Sources: Statistická ročenka (1941), p. 147; 25 let Československa, (25 years Czechoslovakia) (Prague, 1970), p. 251; Československá statistika (relevant years).

Migration

As a result of the relatively unfavourable demographic development in Czechoslovakia, the average age of the population between the two world wars rose from approximately 23 to 27. The main factors in this were the lower birth rate — despite a drop in child mortality from 156 in 1921–5 to 121 per 1,000 births in 1937 — and a simultaneous increase in the life expectancy of the age group from 45 to 64. In addition, people continued to emigrate in search of better economic and social conditions. This stream of emigrants which had started around the turn of the century was only slowed significantly by the slump and the associated immigration prohibitions, particularly to the Unites States of America. Almost half a million inhabitants of Czechoslovakia, in the main from Slovakia and the poorest agricultural regions of the Czech Lands, emigrated to North and South America, France and Germany in the years between 1920 and 1937. Over the same period of time, some 260,000 people — of whom 220,000 came from Slovakia — left their homes as seasonal workers, mostly in West Europe.

In Czechoslovakia itself, unskilled workers wandered westwards to the Czech Lands in search of a livelihood, while the Czechs moved to Slovakia and the Carpatho-Ukraine as civil servants, transport officials, army officers, teachers, office employees and all types of specialists.

The growth of the towns and cities developed hand in hand with advancing industrialisation. In the Czech Lands, growth was in line with the European average, whereas Slovakia lagged some 40 years behind. As late as 1930, 52.6 per cent of the population lived in communities with less than 2,000 inhabitants. Close bonds of kinship continued to exist between the rural and urban populations. Only five municipalities could count in excess of 100,000 inhabitants. Of these, Prague, the capital of the republic, was the biggest with 848,823 people; Brno, the capital of Moravia, had 264,925 and Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, 123,844. The two largest industrial towns, Plzeň with its famous brewery and the Skoda Works, Czechoslovakia’s leading engineering and armaments concern, and Moravská Ostrava with its coal mines and iron and steel works numbered over 140,000 people. By comparison, only 26,675 people lived in Uzhorod, the capital of the Carpatho-Ukraine.

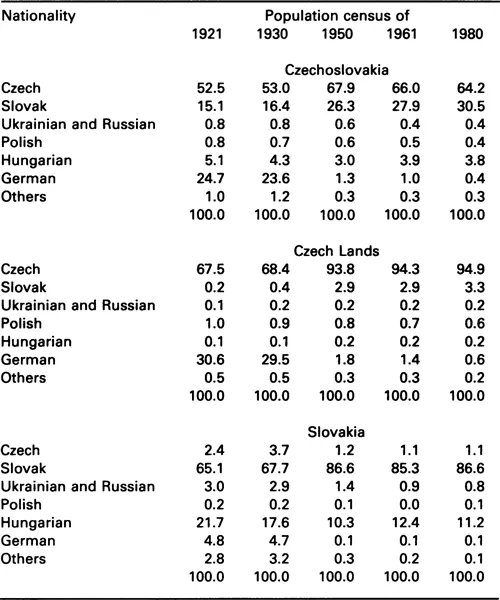

Nationalities

The structure of nationalities in Czechoslovakia (see Table 1.3, classified according to mother tongue) is closely linked with the diverse historical, cultural and economic development of the individual parts of the country. After centuries of independent statehood, the Czechs in the Historical Lands were subjected to the rule of the Habsburg monarchy for a period of 300 years. Among them, groups of Germans had lived for centuries as an important minority. However, from the seventeenth century they shared the same nationality as the ruling elite. And after the collapse of the Central Powers in 1918 their self-confidence developed even further until the 1930s when they came to be used as an instrument for the disintegration of the Czechoslovak state. The Slovaks on the other hand had lived for a thousand years under Hungarian rule and had been subjected to constant pressure of Magyarisation. The two Slav peoples represented the majority of the inhabitants of the First Republic. With the Czechs as the economically, politically and culturally dominant nationality, followed by Slovaks and small minorities of Poles, Russians and Ukrainians, the Slav nationalities made up over 70 per cent of the total population. The remaining 30 per cent was composed of a large and economically influential German population and a not insignificant Hungarian minority. Although the German minority represented a fifth of the Czechoslovak population, there was no compact German-speaking region and they lived in groups of various sizes along the borders of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. In addition, they formed significant linguistic enclaves in central Moravia, in the capital cities of Prague and Bratislava, as well as in Slovakia. The Hungarians numbered less than 5 per cent and lived in south Slovakia as well as being scattered among the Ukrainians and Russians in the Carpatho-Ukraine, while the majority of Poles lived in the Těšín-Ostrava region.

Table 1.3: Structure of population in Czechoslovakia according to nationality, 1921–80 (in %)

Sources: Vývoj společností ČSSR v číslech (Prague, 1965), p. 90; Statistická ročenka (1981).

In multinational Czechoslovakia, the minorities enjoyed incomparably greater democratic freedoms than other minority groups in the neighbouring Successor States. Nevertheless, economic and social life took on national overtones. In isolated cases, grievances were justified but, in the overwhelming majority of cases, national differences were exaggerated in the interests of competing political and financial groups, whereby the many cases of inconvenience and difficulties which the minorities actually suffered, despite the relatively liberal political atmosphere, were exploited for other ends.

Density and the Distribution of Employment According to Economic Sectors

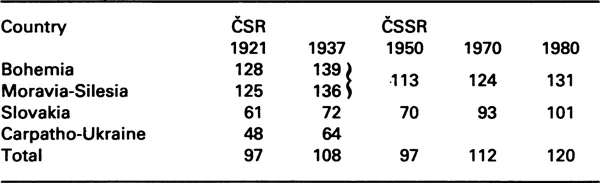

Between 1921 and 1937, the density of the Czechoslovak population increased from 97 to 108 per square kilometre. According to the census of 1937, the population density ranged from 139 in Bohemia to 72 in Slovakia and 64 in the Carpatho-Ukraine (see Table 1.4).

Table 1.4: Density of population in Czechoslovakia, 192–180 (inhabitants per square kilometre)

Sources: As for Table 1.1

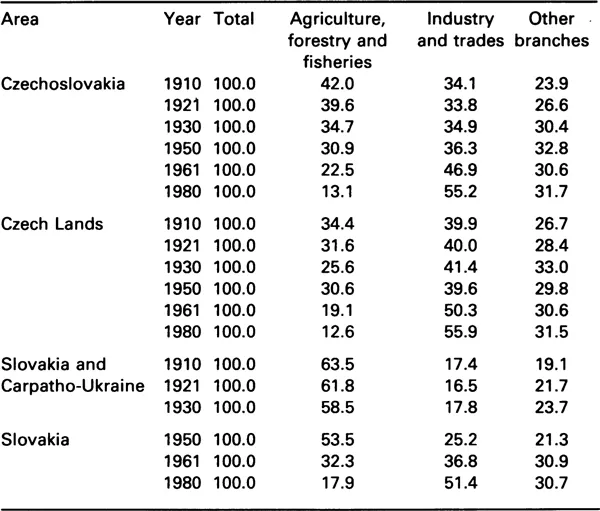

The distribution of employment in Czechoslovakia corresponded with the population density and this underlines the west–east gradient of development which is also revealed by other indicators. Despite the increasing attraction of industrial areas, far more than half of the active population of Slovakia and the Carpatho-Ukraine worked in agriculture, forestry and fisheries between 1921 and 1930. In contrast, the percentage of people working in the Czech Lands in this primary sector of the economy fell from 31.6 per cent in 1921 to 25.6 per cent in 1930. Although the figures in Table 1.5 showing the overall numbers employed in the three main sectors of the economy — agriculture and forestry, trade and industry and the service sector — give the impression of a balanced industrial agricultural economy, they also blur the regional and social-economic differences.

Table 1.5: Occupational distribution of population in Czechoslovakia, 1910–80 (in %)

Sources: Statistická ročenka ČSR (Prague, 1937, 1981); Statistická příučka ČSR IV (Statistical Handbook) (Prague, 1932); Vývoj společnosti ČSSR v číslech (Prague, 1965).

2

Society

Social Classes and Social Mobility

The bourgeoisie

Following the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy and the postwar revolutionary wave which, in Czechoslovakia, developed into a national/democratic revolution, the nobility were displaced from their position as the leading political force by the Czechoslovak bourgeoisie. However, although aristocratic titles were abolished, the majority of these wealthy families retained their estates. Following the Battle of the White Mountain in 1620, the original Czech aristocracy was largely decimated during the seventeenth century and the Bohemian aristocracy which arose in the ensuing decades was descended from noble families in many different parts of Europe. Hence a distinct Czech aristocracy hardly existed in the early twentieth century. In Slovakia, the native aristocracy lost its ethnic identity and merged with the Hungarian nobility. An economically independent bourgeoisie had not developed fully, so that the peasantry formed the backbone of the Slovak nation. In distinction to the neighbouring states where traditional differences between the estates were maintained, a parliamentary democracy developed in Czechoslovakia. Under this system, all citizens were equal before the law. However, this by no means abolished the social differences which continued to exist within Czechoslovak society.

The upper bourgeoisie of the First Republic accounted for around 5 per cent of the population. However, it was no hermetically sealed group. Its members included the highest income groups — numbering some 22,000 families — with incomes, according to income statistics based on tax returns, ranging from 50,000 to 5,000,000 kč per annum stemming from the profits of large companies, as well as financial transactions, stock-exchange dealings, commercial activities and interest from securities. A handful of large landowners, known as the ‘green aristocracy’, were the recipients of Czechoslovakia’s highest incomes amounting to almost 30 per cent of the total declared net agricultural profits. The bourgeois elite included influential statesmen and senior civil servants, leading personalities from the major political parties, as well as the academic professions, particularly university professors, physicians and lawyers who were held in high esteem by society at large.

The middle strata

One of the most numerous and highly differentiated social groups was the middle strata, which encompassed almost 20 per cent of the economically active population (5.6 million). In the main, it was made up of tradesmen, craftsmen, shopkeepers, specialists, small businessmen and dealers, white-collar workers and civil servants. Between 1921 and 1930, the middle strata shrunk by 3 p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Tables and Figures

- Editor’s Introduction

- Introduction

- Part 1: Czechoslovakia, 1918–45

- Part 2: Czechoslovakia after the Second World War

- Select Bibliography

- Index