![]()

Listening to children’s voices: moral emotional attributions in relation to primary school bullying

Dawn Jennifera and Helen Cowieb

aResearch Unit, Business Affairs, Department for Communities and Social Inclusion, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia; bFaculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Surrey, Surrey, UK

This study explored 10- and 11-year-old students’ (N = 64) moral emotional attributions in relation to other and self in peer-to-peer bullying scenarios in primary school. Data were gathered using one-to-one semi-structured interviews facilitated by the use of a series of pictorial vignettes depicting a hypothetical story of peer bullying. The results demonstrated that worry and to a lesser extent shame were most often attributed to the other as victim character, indifference and pride to the other as bully character, and worry and shame to the other as follower character. Participants mostly attributed worry to self as victim, shame and worry to self as bully, and shame to self as follower. The findings are discussed in relation to the role of peers in addressing school bullying, such as through peer support. There are implications for school-based interventions to address bullying that facilitate self-awareness and empathy in children and young people as a means of addressing such behaviour.

Introduction

Research on general attitudes to peer-to-peer bullying suggest that the majority of children are opposed to such behaviour and supportive of victims (e.g. Boulton and Underwood 1992). Not only do children judge that it is morally wrong to hurt others or to treat others unfairly, they also perceive that aggression is wrong and harmful (Murray-Close, Crick, and Galotti 2006; Shaw and Wainryb 2006). In addition, children of all ages are likely to be critical of behaviours that target others’ well-being (Shaw and Wainryb 2006). Nevertheless, substantial numbers of primary school children report being bullied, and bullying others, on a regular basis (Shaughnessy and Jennifer 2007). More worryingly, sadistic types of bullying have emerged as a subtype of aggression, suggesting that some children experience positive arousal from inflicting harm on another (Bosacki, Marini, and Dane 2006). Research into school bullying that focuses on the area of moral reasoning could have important implications for interventions that reduce and prevent such conduct (Menesini et al. 2003).

A few studies have investigated children’s understanding of others’ emotions in relation to peer-to-peer school bullying. In a cross-national study using pictorial vignettes, participants from Portugal and Spain, aged 9, 11 and 13 years, were interviewed regarding their emotional attributions to other and self as the bully and the victim characters (del Barrio et al. 2003). Participants attributed rejected (55%), sad (49%), and ashamed and afraid (13% each) to other as victim. Similar emotional attributions were made to self as victim. In terms of other as bully, happy (60%), pride (27%) and guilt (8%) were attributed. In contrast, almost half of the sample reported that they would feel guilt (45%) as the bully and, to a lesser extent, happiness (17%) and pride (11%).

These findings regarding bullies and moral development are supported by the results from another European study, which explored bullies’, victims’ and outsiders’ feelings in relation to the task of putting themselves into the role of the bully in a bullying situation (Menesini et al. 2003). The study focused on emotions of moral responsibility (guilt and shame) and emotions of moral disengagement (indifference and pride). Compared with victims and outsiders, bullies attributed higher levels of moral disengagement emotions to the bully in the bullying scenario. Analysis of specific mechanisms of moral disengagement revealed that bullies possessed a main profile of egocentric reasoning. The authors suggest that, when putting themselves into the role of the bully, personal motives and the benefits of bullying behaviour were sufficient to justify negative and antisocial behaviours.

Using a set of pictorial vignettes, Ttofi and Farrington (2008) asked 10–12-year-olds questions about the emotions they would have felt, including anger, shame, remorse or guilt, if they were in the position of the child in the vignette. Two types of shaming – disintegrative shaming and integrative shaming – had different effects on the ways in which the children anticipated managing shame. Children who scored high on disintegrative shaming scored high on maladaptive forms of shame management. Disintegrative shaming relates to rejecting parenting styles, usually associated with the suppression of empathy. The authors acknowledge the difficulty involved in enhancing children’s moral competence by working with emotions of shame and guilt, but they propose that the management of emotions and behaviour is closely bound to the social context and the quality of relationships, both in the family and within the peer group. This study confirms the role of school in promoting moral values through restorative practices and through the teaching of emotional literacy.

Since research evidence suggests that the social group context within which bullying takes place both promotes and sustains bullying behaviour (Salmivalli 2010), a major limitation of the previous research is the focus on emotional moral attributions to the bully, or the bullies as a homogeneous group, and the victim, to the exclusion of other individuals involved in bullying. It is important to give attention to the wider social group context that influences whether aggressive behaviour between group members will occur (DeRosier et al. 1994). For example, bystanders in the bullying context have been described as ‘those who watch, avert their eyes, pretend not to notice, egg on protagonists, stand on the outskirts, and provide an audience’ (Hazler 1996, 19). Research by Salmivalli et al. (1996) suggests that bystanders play a number of roles in the bullying episode from simply providing an audience to becoming actively involved in the interaction between the bully and the victim. Hazler (1996) observes that bystanders make up the majority in any given bullying situation, yet they receive the least research attention and their potential contribution to influence such situations goes largely unnoticed.

In terms of moral reasoning, Jones, Manstead, and Livingstone (2011), using a text-message bullying scenario with 10–11-year-olds, indicated the key role played by the group in shaping how children respond to bullying. They found that pride following a bullying episode was associated with affiliation with the bullying group and concluded that group identification influences the individual’s response to a group-relevant event. Their findings indicate that children value the protection provided by affiliation with a dominant group of peers. This group affiliation plays a powerful role in whether members resist or support the aggressive intentions of others, also influences the group-based emotions of pride, shame and anger experienced as a consequence, and highlights the roles other than perpetrator and target that children play in the bullying process (Salmivalli 1999).

Therefore, the main aim of the present study was to explore children’s emotional attributions and moral reasoning in relation to primary school bullying, and their understanding of the bullying relationship. Here we report the results concerning the nature of the relationship portrayed in the story, the moral emotional experiences attributed to characters in the story, and how children related to and empathised with the characters’ emotional states.

Method

Design

One-to-one interviews were carried out using a semi-structured interview schedule devised to capture children’s knowledge and reasoning about school bullying facilitated by the use of a series of pictorial vignettes depicting a hypothetical story of peer-to-peer bullying adapted from the Scripted-CArtoon Narrative of Bullying (SCAN) drawings (Almeida et al. 2001). Data were collected during 2003/04.

Participants

Letters were mailed to all primary and secondary school head teachers in a south-west London (UK) local authority inviting them to participate in the study. Following telephone conversations with several prospective schools, two primary schools agreed to participate. A principle of consent was adopted that required the active consent of the child and the passive consent of the adult (Thomas and O’Kane 1998). Head teachers sent a letter to parents seeking ‘opt-in’ consent for their child to be approached to participate. Following this, all students from year 6 were invited to participate in the study at an introduction session; all consented to take part (66 children). However, not all volunteers were available to participate owing to absence at the time of data collection; the final sample consisted of 64 participants, 30 males (47%) and 34 females (53%), aged 10–11 years.

Materials

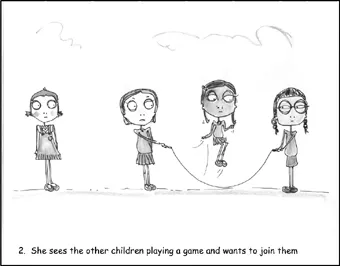

The pictorial vignettes were adapted and modified for a UK sample from the SCAN drawings (Almeida et al. 2001) developed in Europe. The vignettes were redesigned by a young art student to reflect the UK sample in terms of primary school age, ethnic diversity and primary school culture (i.e. the wearing of school uniform). The intention of the story illustrated by the drawings was to convey the idea of an imbalance of power and repeated aggressive behaviours such that the interpretation of the story was in terms of intentional and hurtful actions, rather than isolated or irregular events. The set of 14 A4-size drawings included one neutral vignette, followed by nine vignettes (depicting mean and unpleasant behaviours) performed by one individual or by a group of peers (see Figure 1 for an example). A short caption describing the content of the vignette was included with each (e.g. ‘She sees the other children playing a game and wants to join in’; see Table 1 for a summary). The remaining four vignettes completed the set of drawings, each representing a different outcome to the story in terms of distinct roles taken by adults and peers (optimistic: the children all play together; pessimistic: the victim remains alone; peer social support: the victim seeks the support of a peer; and adult social support: the victim seeks the support of an adult). A masculine and a feminine version of the same story were used for males and females, respectively. Where necessary, captions were re-written to address anomalies arising from translation into English, and to incorporate idiomatic vocabulary; for example, in vignette 5, ‘recess’ was changed to ‘playtime’; and in vignette 7, ‘ground’ was changed to ‘floor’.

Figure 1. An example of one of the pictorial vignettes (female version).

Table 1. Content of the 10 pictorial vignettes | Behaviour | Caption |

| 1. Neutral | The girl is new to the school and it’s her first day. |

| 2. Social exclusion | She sees the other children playing a game and wants to join them. |

| 3. Teasing | She is wearing a different uniform and the other children start teasing her about it. |

| 4. Physical obstruction | The school day is over and when she is leaving the classroom she gets blocked by a classmate. |

| 5. Attack on personal possessions | During playtime the other children get together and grab her schoolbag and start to pull out her books. |

| 6. Real damage to personal possessions | She gets to her table and finds her book torn and notices one of her classmates walking away holding a pair of scissors. |

| 7. Group physical attack | On the way to the classroom she gets pushed over by the other children and falls down. Her books are all over the floor, but the others walk away. |

| 8. Coercion | The other children get together and hold out a cigarette, telling her to smoke. |

| 9. Blackmail | The children grab her and threaten to harm her if she doesn’t steal money from another child. |

| 10. Social isolation | She stands alone behind a tree, away from the playground and from the other children. |

To assess the modifications to the vignettes, pre-test interviews were carried out with 12 participants from the main sample. The majority of these participants (82%) described the nature of the relationship as bullying. The remaining 18% described the behaviours as aggression, without explicitly mentioning bullying. This was the intended outcome and supported the effectiveness of vignettes to study children’s constructions of bullying in school (Ojala and Nesdale 2004). The data from the pre-test interviews were analysed along with the data from the main study.

During presentation of the vignettes, participants were interviewed using a semi-structured interview schedule devised to capture children’s knowledge and reasoning about bullying in school (del Barrio et al. 2003). This included questions about narrative and causal attributions (e.g. ‘After looking carefully at the drawings, what would you say is happening in the story, from the beginning to the end?’; ‘What do you think is happening with this girl/boy? [pointing to one character in two or three different drawings, then another character, etc.]); moral emotional attributions (worry, shame, indifference, pride) to the characters in the story (e.g. ‘Can anyone in this story feel ashamed? Why?’); and moral emotional attributions to self in the role of the characters (e.g. ‘And if you were one of these boys/girls could you also feel ashamed? [pointing to the characters in turn]. Why?’). Interview questions were re-written to incorporate idiomatic vocabulary where necessary. In addition, in consideration of bullying from a wider social group context, questions relating to the role of characters other than the bully and the victim were included in the interview schedule. The full interview schedule can be obtained from the first author on request.

Procedure

Interviews were conducted during lesson time by the first author, each lasting approximately 20 minutes. Each interview commenced with standardised instructions regarding the general nature of the interview, confidentiality, anonymity and the right to withdraw, and ended with a debriefing, including resources for outside support should the need arise. With ...