The purpose of this chapter is to both provide a contextual framework for the other chapters in this book and to advance an argument that might be used to explain the dynamics of recent political developments in the region. The argument is constructed as follows. First, I review the dynamics of the new geoeconomics of capital in Latin America and the corresponding politics. The aim is to provide a theoretical framework for the subsequent analysis. The chapter then elaborates on certain dynamics associated with the political economy of two types of capitalism, with reference here to the particular way in which these forms of capital are combined in the current context of capitalist development in the region. The third part of the chapter provides a brief review of the economic and political dynamics that led to the pink tide of regime change in South America. Subsequently, we provide a brief review and analysis of the policy dynamics of the governments formed in the wake of this seatide of regime change and the associated progressive cycle in Latin American politics. The chapter then turns towards the recent pendulum swing of electoral politics towards the hard right of neoliberal policy reform. The chapter ends with a brief discussion of the forces engaged in what appears to be the end of the progressive cycle—forces mobilised by the advance of resource-seeking ‘extractive’ capital and various contradictions of capitalist development.

The new geoeconomics and geopolitics of capital

By the ‘new geoeconomics of capital’ reference is made to the confluence and interaction of two types of capitalism, two modalities of accumulation: (i) industrial capital(ism) based on the exploitation of the ‘unlimited supply of surplus labour’ generated by the capitalist development of agriculture, what we might regard as ‘normal capitalism’ or ‘capitalism as usual’; and (ii) the advance of extractive capital based more on the exploitation of nature (extraction of its wealth of natural resources) as well as the exploitation of labour (Giarracca and Teubal, 2014; Gudynas, 2009, 2011; Svampa and Antonelli, 2009; Svampa, 2015; Veltmeyer and Petras, 2014). These two modalities of accumulation—one based on the advance of industrial capital and the other of extractive capital—do not exist in isolation, and in many conjunctures of the capitalist development process are combined in one way or the other. The point is that each form of capital, and both modalities of accumulation, has its distinct development and resistance dynamics that need to be differentiated and clearly distinguished for the sake of analysis and political action.

A second dimension of the geoeconomics of capital has to do with reconfiguration of global economic power over the past three decades, with the advent of China’s voracious appetite for natural resources and commodities, in particular industrial minerals and metals, and fossil fuels. This ‘development’ implicates not just rapid economic growth and the Chinese demand for natural resources but also the ‘emerging markets’ of the BRICS, which helped fuel the growth of a demand for these resources on capitalist markets and a primary commodities boom. This boom in the demand for natural resources, and an associated decade of rapid economic growth in Latin America,1 fuelled by record commodity prices spurred by Chinese demand and consumer demand in the BRICS, coincided in Latin America with a progressive cycle of governments formed in the wake of a pink (and red) tide of regime change … governments oriented towards the ‘new developmentalism’ (a social policy of ‘inclusive development’, or poverty reduction) as well as an extractivist economic development strategy.

As for the geopolitics of this development process the chapter brings into focus the progressive cycle of postneoliberal policy regimes formed in this changing of the political tide. The policy regime of these ‘progressive’ or left-leaning governments has been described as neoextractivism, with reference to the use of the fiscal revenues derived by these governments from the export of raw materials to finance their poverty reduction program (Gudynas, 2009; Svampa, 2017). In short, the economic model used by these progressive governments to make public policy in the area of development has two pillars: neodevelopmentalism, or the post-Washington Consensus on the requirement of a more inclusive form of development based on poverty reduction, and an extractivist strategy of capital accumulation.

The political economy of extractive capitalism

An extractivist strategy based on the export of natural resources in primary commodities form has long been the dominant approach of governments in the region towards national development, an approach that is reflected in the emergence of an international division of labour in which countries on the periphery of the world system serve as suppliers of raw materials and natural resources with little to no value added processing or industrialisation.2

Turning to the question of the geoeconomics and geopolitics of capita in the current context of neoliberal globalisation, it can be traced back to the 1980s, to conditions and forces generated by the establishment of a then ‘new’ world order of free market capitalism, designed to liberate the ‘forces of economic freedom’ from the regulatory constraints of the development state. This world order entailed a series of policy guidelines or ‘structural reforms’ in macroeconomic policy such as privatisation of the means of production), deregulation of markets and the liberalisation of trade and capital flows. Implementation of these reforms resulted in the destruction of forces of production in both agriculture and industry that had been built up in previous decades under the aegis of the development state. It also unleashed a massive inflow of capital in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly resource-seeking extractive capital, which by the end of the 1990s dominated the flows of capital into the region.3

Although the service sector at the turn into the new millennium still accounted for almost half of FDI inflows, this dominance of extractive capital in FDI inflows either held steady or trended upwards in the years 2002 to 2008 of the commodities boom (ECLAC, 2012). Despite the global financial and economic crisis at the time, FDI flows towards Latin America and the Caribbean in 2008 reached a record high (US$128.3 billion), an extraordinary development considering that FDI flows worldwide at the time had shrunk by at least 15 per cent. This countercyclical trend signalled the continuation of the primary commodities boom and the steady expansion of extractive capital in the region—until 2012, when the prices of many key commodities began to fall or collapse, heralding the beginning of the end of the boom (Harrup, 2019; Wheatley, 2014).

In 2009, barely a year into what has been described as a ‘global financial crisis’,4 Latin America received 26 per cent of the capital invested globally in mineral exploration and extraction. And according to the Metals Economics Group, a 2010 bonanza in world market prices led to another increase of 40 per cent in investments related to mineral exploration, with governments in the region, both neoliberal and post-neoliberal, competing fiercely for this capital. In 2011, on the eve (the year before) of an eventual collapse of the primary commodities boom, South America attracted 25 per cent of global investments related to mining exploration, the production of fossil and bio-fuels, and agro-food extraction (Kotze, 2012).

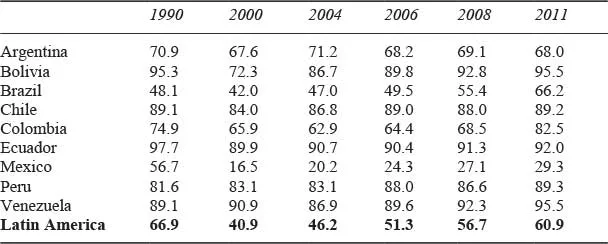

Large-scale investment in the acquisition of land and the extraction of natural resources (in the form of metals/minerals, fossil fuels and agro-food products) was a defining feature and a fundamental pillar of the model used by the progressive regimes formed in the pink wave to make public policy in the area of development. The other pillar was extractivism, or to be precise, neoextractivism, which led to a process of rapid economic growth, averaging 5–6 per cent over the progressive cycle, which coincided almost precisely with the progressive policy cycle and a process of primarisation (Cypher, 2010)—or, to be more precise, reprimarisation, inasmuch as the exports of most of the countries in the region long involved the export of commodities in primary form (on this see Table 1.1)—but this fundamental long-term structural trend, as well as the commodities boom-bust cycle, was accentuated in a new development-resistance cycle that emerged with the advance of extractive capital in the Latin American development process.

The policy dynamics of the pink tide and the associated or resulting cycle of development and resistance—NB each cycle in the capitalist development process generates a corresponding development in the forces of resistance—has been analysed at length if not in depth. Besides, and in addition to the question as to the fundamental pattern and dynamics of capital inflows in the form of FDI, at issue in this analysis are problems—to which I will make only brief reference—such as:

Table 1.1 The structure of Latin American exports, 1990–2011

Source: ECLAC (2004, 2012).

1 The policy outcomes of the economic development model used to formulate policy in the area of development … a combination of neodevelopmentalism (the quest for inclusive development … a strategy formulated in the Post-Washington Consensus formed in the 1990s) and extractivism. One of the main policy outcomes, which relates to both this consensus and a protracted war fought by the World Bank and the United nations since at least the mid-1970s, is the dramatic reduction in the rate of poverty achieved by these governments over the course of the decade-long cycle of progressive policies … up to 40–50 per cent in the case of a number of progressive regimes formed in the wake of the pink tide (see the discussion below).

2 The contradictions of extractive capitalism (see the discussion below), when added to the fundamental contradiction of labour and capital and the secondary contradiction of centre-periphery relations within the world capitalist system, introduces an entirely new dynamic into the forces of resistance to the advances of capital in the development process. This dynamic relates particularly to the contradiction between the strategy pursued by the progressive postneoliberal regimes in the region, which, in the case of Ecuador and Bolivia, implicates the sought-for condition of vivir bien, or buen vivir (living well in solidarity and harmony with nature)—and the destructive and negative impacts of extractive capital.

3 The forces of resistance and the class struggle formed in response to the advance of extractive capitalism: a struggle of indigenous and non-indigenous communities on the extractive frontier to reclaim their territorial rights to the commons of land, water, resources for production and subsistence), and in protest against the negative socioenvironmental impacts of extractive capital and its destructive operations. On the complex and diverse social and political dynamics of this resistance see, inter alia, Barkin and Sánchez (2017); Bebbington and Bury (2013); Bollier (2014); and Dangl (2007).

The contradictions of capitalism

Marx’s theory regarding capitalism is that it is beset by contradictions that are reflected in a propensity towards crisis and class conflict (Marx, 1975 [1866]). The source of this conflict is an economic structure based on the capital-labour relation and the exploitation of workers (Labour) by capitalists (Capital). The capitalist class, it is argued, is driven by the need to accumulate—to profit from the labour power of workers. The developmental dynamics of this relation of capital to labour—the driving force of capitalist development—are both structural and strategic. The structural dynamics of the system are manifest in conditions that are, Marx argued, ‘independent of our will’ and thus not of our own choosing and objective in their effects—an objectivity that accords with each individual’s class position. The strategic or political dynamics of the capital–labour relation, the foundation of the social structure in capitalist societies, are reflected in class consciousness, basically a matter of workers becoming aware of their exploitation and acting on this awareness. In this context, each advance of capital in the development process generates forces of resistance and social change.

Marx’s theory of Capital, as well as most studies by Marxist scholars on the contradictions of capitalism, is predicated on the capital–labour relation and the capitalist development of agriculture—the dispossession and proletarianisation of the direct producers, the peasantry of small-scale peasant farmers, and the exploitation of the ‘unlimited supply of surplus labour’ generated by the capitalist development process (Araghi, 2010). As mentioned above each advance of capital in the development process generates forces of resistance, social relations of conflict and contradictory outcomes in which Capital appropriates the social product of cooperative labour. The result, at the level of the capital–labour relation, is a protracted class struggle over land and labour—a struggle that dominated the political landscape in the twentieth century—and a propensity towards crisis. At the level of international relations this fundamental contradiction has manifested itself in the uneven development of the forces of global production and a relation of dependency between the centre and the periphery of the world system—between the imperial state in its quest for hegemony over the system and the forces of anti-imperialist resistance (Borón, 2012).

The 1970s can be viewed as a decade of diverse structural and strategic responses to a systemic crisis, which put an end to what some historians have dubbed ‘the golden age of capitalism’. One of these responses was the construction of a ‘new world order’ based on the belief in the virtues of free market capitalism and the need to liberate the ‘forces of economic freedom’ from the regulatory constraints of the development state. The installation in the 1980s of this new world order by means of a program of ‘structural reforms’ in macroeconomic policy (globalisation, privatisation, deregulation and the liberalisation of the flow of goods and capital) gave rise to a new development dynamic on the Latin American periphery of the system—the advance of extractive capital—and with it new forces of resistance that brought to the fore what we might conceive of as the ‘contradiction(s) of extractive capitalism’.

The advance of extractive capital in the form of large-scale foreign investment in the acquisition of land—‘landgrabbing’, in the discourse of Critical Agrarian Studies (Borras et al., 2012)—and the extraction of natural resources took the form of a primary commodities boom from 2002 to 2012, and what Maristella Svampa describes as the ‘commodities consensus’ and what others (for example, Gudynas, 2009) understand and have described as ‘neoextractivism’ (the combina...