![]()

I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

Jason A. Colquitt

University of Florida

Jerald Greenberg

University of Florida

Cindy P. Zapata-Phelan

University of Florida

The Distributive Justice Wave

Stouffer et al.: Relative Deprivation

Homans: Fairness in Social Exchanges

Blau: The Role of Expectations

Adams: Equity Theory

Walster et a1.: Equity Theory Revised

Leventhal and Deutsch: Multiple Allocation Norms

The Procedural Justice Wave

Thibaut and Walker: Fairness in Dispute Procedures

Leventhal: Fairness in Allocation Procedures

Procedural Justice Introduced to Organizational Scholars

Early Empirical Tests of Procedural Justice

The Interactional Justice Wave

Bies: Fairness in Interpersonal Treatment

Early Empirical Tests of Interactional Justice

Construct Clarification

The Integrative Wave

Counterfactual Conceptualizations

Group-Oriented Conceptualizations

Heuristic Conceptualizations

Conclusion

We present a historical review of the field of organizational justice. Our analysis focuses on “the modern era” of the literature, beginning with research on relative deprivation in 1949 and extending to the present day. Specifically, we organize our discussion with respect to four loaves of research and theorizing that have contributed to the development of organizational justice. These include: (a) the distributive justice wave, in which scholars focused on the subjective process involved in judging equity and other allocation norms; (b) the procedural justice wave, in which scholars focused on rides that foster a sense of process fairness; (c) the interactional justice wave, in which the fairness of interpersonal treatment was established as a unique form of justice; and (d) the integrative wave, in which successors to earlier theories provided frameworks for integrating the various justice dimensions. We highlight the ways in which various perspectives influenced one another, and identify seminal contributions graphically in the form of timelines.

The concept of justice has interested scholars over millennia. Dating back to antiquity, Aristotle was among the first to analyze what constitutes fairness in the distribution of resources between individuals (Ross, 1925). This theme was rejuvenated in the seventeenth century by Locke's (1689/1994) writings about human rights and Hobbes's (1651/1947) analysis of valid covenants, and was revisited in the 19th century by Mill's (1861/1940) classic notion of utilitarianism. Despite some differences, these philosophical approaches share a common prescriptive orientation, conceiving of justice as a normative ideal. Although this orientation continues to flourish in contemporary philosophy through the influential work of Rawls (1999, 2001) and Nozick (1974), today's scholarly discourse about justice is supplemented by the descriptive approach of social scientists (for a comparison, see Greenberg & Bies, 1992). These conceptualizations focus on justice not as it should be, but as it is perceived by individuals. In this sense, understanding matters of justice and fairness (terms that tend to be used interchangeably) requires an understanding of what people perceive to be fair.

This descriptive orientation has been of keen interest to social scientists from many disciplines focusing on a wide variety of issues and contexts (Cohen, 1986). Concerns about fairness, for example, have featured prominently in treatises on the acquisition and use of wealth and political power (Marx, 1975/1978), opportunities for education (Sadker & Sadker, 1995), and access to medical care (Daniels, Light, & Caplan, 1996). Fairness issues also are discussed in research on methods used to resolve disputes (Brams & Taylor, 1996), the interpersonal dynamics of sexual relations (Hatfield, Greenberger, Traupmann, & Lambert, 1982), and even the evolution of mankind (Sober & Wilson, 1998). Our concern—and the focus of this book as a whole—is on justice in a different context, the workplace.

Although attention to matters of justice in the workplace was of at least passing interest to classical management theorists such as Frederick Winslow Taylor (Kanigel, 1997) and Mary Parker Follett (Barclay, 2003), it wasn't until the second half of the 20th century—when social psychological processes were applied to organizational settings—that insights into people's perceptions of fairness in organizations gained widespread attention. Fueled by early conceptualizations such as balance theory (Heider, 1958), cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), psychological reactance (Brehm, 1966), and the frustration-aggression hypothesis (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939; see Homans, 1982), the burgeoning fields of organizational behavior and human resources management found the conceptual tools required to investigate the fundamental matter of justice in the workplace.

Concerns about organizational justice are reflected in several different facets of employees' working lives. For example, workers are concerned about the fairness of resource distributions, such as pay, rewards, promotions, and the outcome of dispute resolutions. This is known as distributive justice (Homans, 1961; see also Adams, 1963, 1965; Deutsch, 1975; Leventhal, 1976a). People also attend to the fairness of the decision-making procedures that lead to those outcomes, attempting to understand how and why they came about. This is referred to as procedural justice (Thibaut & Walker, 1975; see also Leventhal, 1980; Leventhal, Karuza, & Fry, 1980). Finally, individuals also are concerned with the nature of the interpersonal treatment received from others, especially key organizational authorities. This is called interactional justice (Bies & Moag, 1986; see also Greenberg, 1993a). Collectively, distributive justice, procedural justice, and interactional justice are considered forms of organizational justice, a term first used by Greenberg (1987b) to refer to people's perceptions of fairness in organizations.

These organizational justice dimensions are important to people on the job for a variety of reasons. For example, fair treatment provides support for the legitimacy of organizational authorities (Tyler & Lind, 1992), thereby discouraging various forms of disruptive behavior (Greenberg & Lind, 2000) and promoting acceptance of organizational change (Greenberg, 1994). Perceptions of fairness also reinforce the perceived trustworthiness of authorities, reducing fears of exploitation while providing an incentive to cooperate with one's coworkers (Lind, 2001). On a more personal level, fairness satisfies several individual needs (Cropanzano, Byrne, Bobocel, & Rupp, 2001), such as the need for control (Thibaut & Walker, 1975) and the needs for esteem and belonging (Lind & Tyler, 1988). And, of course, behaving in ways perceived to be fair also satisfies people's interest in fulfilling moral and ethical obligations (Folger, 1998).

In our quest to address the question raised in the title of this chapter, “What is organizational justice?,” we present a history of the field. Given that considerable attention has been paid to organizational justice in the literature of late (as attested to by the size of this book, if nothing else), we believe it would be useful to trace the development of the major lines of intellectual thought that have led the field to where it is today (see also, Byrne & Cropanzano, 2001; Cohen & Greenberg, 1982; Colquitt & Greenberg, 2003; Cropanzano & Randall, 1993). By pointing out the major themes and milestones that have directed scholarship over the last 50 years, our intent in this chapter is: (a) to help readers of the Handbook of Organizational Justice appreciate how the field's major ideas unfolded, and (b) to give researchers new insight by allowing them to learn lessons from the past.

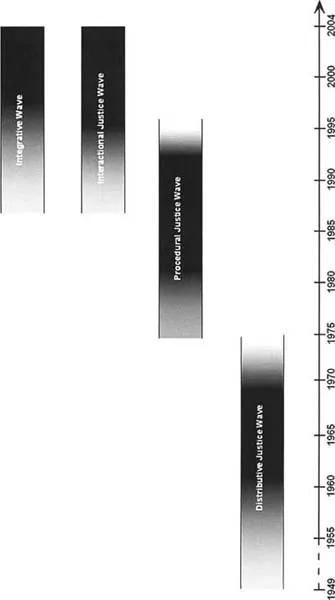

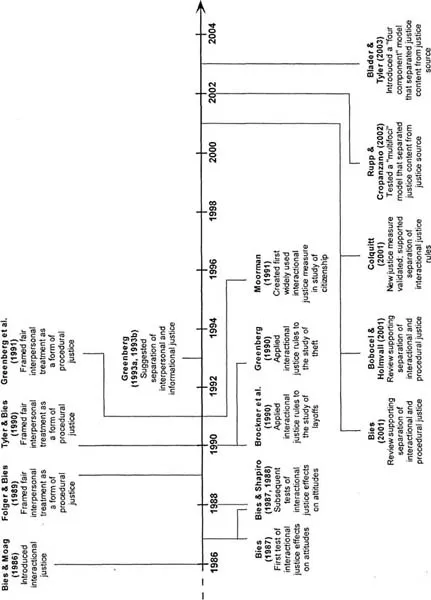

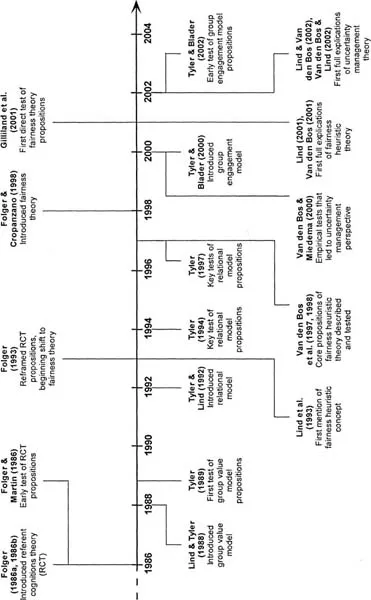

To achieve these objectives, we have organized the history of organizational justice into four major waves that have defined research and theory development. These four waves appear together in Fig. 1.1, with the darker areas representing more intense periods of research activity within each wave. First, the distributive justice wave, spanning the 1950s through the 1970s, focused on fairness in the distribution of resources. The procedural justice wave, which took root in the mid-1970s and continued through the mid-1990s, shifted the primary focus to the fairness of the procedures responsible for reward distributions. Then, beginning in the mid-1980s and continuing today, attention was paid to the interpersonal aspects of justice, defining the interactional justice wave. Simultaneously with this interactional wave, another stream of theory and research sought to combine aspects of the various organizational justice dimensions. This stream, which has gained dominance in the first few years of the 21st century, we refer to as the integrative wave.

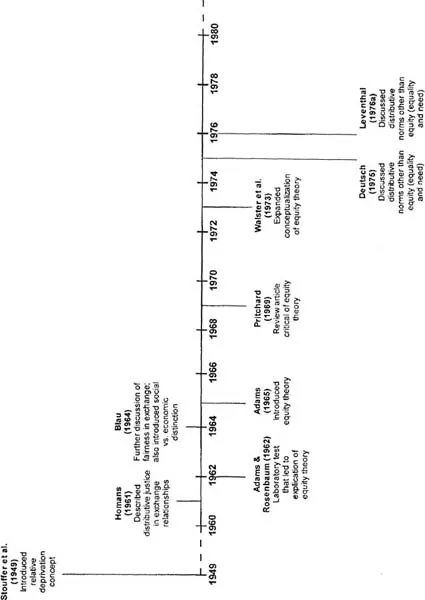

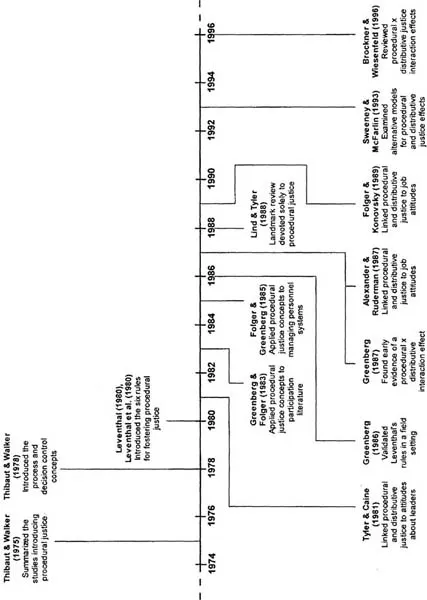

By using the metaphor of waves to present these four intellectual themes, we are acknowledging the surge of interest that defined them as well as their ebb and flow of scholarship along the conceptual shoreline. Our presentation of each wave is organized with respect to a timeline that identifies various landmark contributions, papers and publications that shaped the development of the field. Each wave is divided into multiple sections, with the key contributions to each section appearing at the same altitude within each timeline (see Figs. 1.2 to 1.5).

FIG. 1.1. The four waves of organizational justice theory and research.

FIG. 1.2. The distributive justice wave.

FIG. 1.3. The procedural justice wave.

FIG. 1.4. The interactional justice wave.

FIG. 1.5. The integrative wave.

THE DISTRIBUTIVE JUSTICE WAVE

Inherent in the nature of employee relations is the fact that not all workers are treated alike. At the outset, some get hired for jobs whereas others do not. And, among those who are hired, some enjoy rapid promotions and the higher pay and status that come with it, whereas others advance less quickly. The fact that people routinely are differentiated in the workplace lends itself to triggering concerns about fairness. It is not surprising, then, that the earliest attention to matters of justice in organizations concerned the distributions of rewards. Specifically, such matters were of considerable concern to social scientists in the three-decade period spanning the 1950s through the 1970s—a period to which we refer as the distributive justice wave (see Fig. 1.2).

Stouffer et al.: Relative Deprivation

In an article appearing in the military magazine, The American Soldier, Stouffer, Suchman, DeVinney, Star, and Williams (1949) summarized 4 years of research on the attitudes of U.S. troops during World War II. One of the questions military researchers asked Army soldiers was, “In general, have you gotten a square deal in the Army?” (p. 230). The most prominently occurring category of comments concerned perceived unfairness with the Army's promotion system. The concept of relative deprivation was expressed first in the following passage foreshadowing a surprising and seemingly counterintuitive trend emerging from these data:

Data from research surveys to be presented will show, as would be expected, that those soldiers who had advanced slowly relative to other soldiers of equal longevity in the Army were the most critical of the Army's promotion opportuneties. But relative rate of advancement can be based on different standards by different classes of the Army population. (Stouffer et al., 1949, p. 250, emphasis in original)

Stouffer et al. (1949) identified an example of this phenomenon with respect to promotion opportunities among soldiers stationed in the Military Police (MPs) and their counterparts in the Air Corps. Specifically, although MPs with a high school or college degree had a 34% chance of being promoted to noncommissioned officer, equally qualified members of the Air Corps had a 56% chance of receiving the same promotion. Interestingly, however, members of the Air Corps expressed higher levels of personal frustration. Further analysis of this surprising finding suggested that MPs did not compare themselves to members of the Air Corps. Instead, MPs who earned promotions felt special because they were in the top one-third of their peer group, whereas soldiers in the Air Corps who earned promotions felt less special; they achieved merely what the majority of their peers had achieved. Not surprisingly, the denial of promotion among members of the Air Corps was sufficiently rare to trigger feelings of frustration among them.

Another interesting pattern of responses was observed among African American soldiers (Stouffer et al., 1949). Troops stationed in the North and the South were asked to indicate how fairly they were treated by town police, whether they were treated well in the public bus service, and ...